|

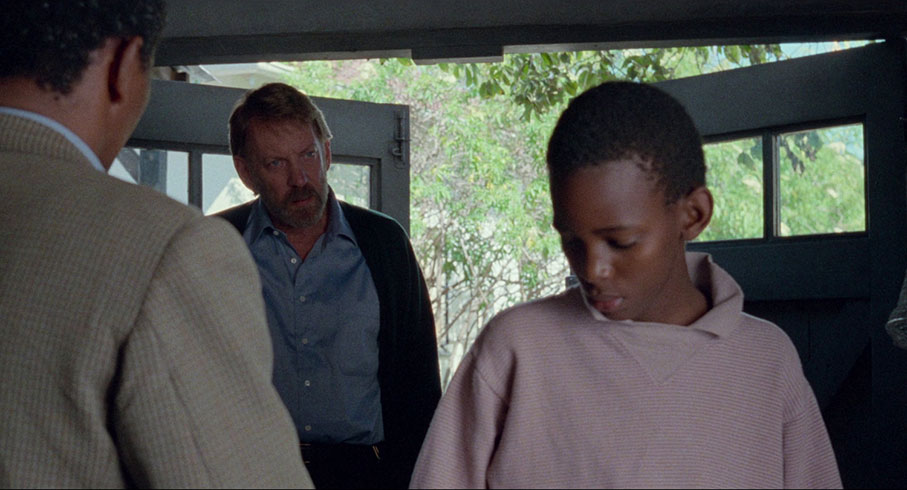

South Africa, 1976. A protest in the Johannesburg township of Soweto leads to the deaths at the hands of the police of many black South Africans. One who disappears is the son of gardener Gordon Ngubene (Winston Ntshona), who turns to his employer, teacher Ben Du Toit (Donald Sutherland) for help. Ben, who lives with his wife Susan (Janet Suzman) and their children, finds out that Gordon's son, supposedly killed in the protest, was actually imprisoned and tortured. Then Gordon is arrested. Ben intercedes on his behalf and is then told by Stanley (Zakes Mokae) that Gordon has supposedly killed himself in his cell. Not convinced at all, Ben searches for justice, aided by journalist Melanie Bruwer (Susan Sarandon), at considerable threat to himself from the police, led by Captain Stolz (Jurgen Prochnow).

A Dry White Season, based on the novel by André Brink, was one of several films of the later 1980s dealing with apartheid, the system of racial segregation which held sway in South Africa from 1948 until it was repealed in 1991. This film is significant in another way, in that Euzhan Palcy became the first woman of colour to direct a film for an American major studio. Apartheid now belongs in the past (though with the far right on the rise, there's no grounds for complacency), but A Dry White Season remains a powerful, angry film not easily dismissed. The title comes from a poem by Mongane Wally Serote, which serves as the epigraph to Brink's novel.

Apartheid was imposed by the minority white population of South Africa, who had the highest status in the country. The white and black population was separated by law, in public and at events, and in housing and employment, and interracial marriage or sexual relations was illegal. As a result, South Africa faced international condemnation and economic sanctions. Within the country, the ruling National Party cracked down on growing internal resistance and violence which left thousands of people dead or in detention. The government justified its actions as defending themselves against external and internal threats which they claimed to be Communist-influenced.

André Brink (1935-2015) was a novelist and poet, who also taught English at the University of Cape Town. He wrote in both Afrikaans and English. He was a longterm opponent of apartheid and as a result attracted censorship in his native country. A Dry White Season, published in 1979, was his fifth novel. It was initially banned, though Brink had copies published by an underground press and secretly distributed. In 1980, the novel was awarded the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize.

The novel has some differences to the film version (written by Colin Welland and Euzhan Palcy), but in most respects is faithful to it. The novel is told in flashbacks with a frame narrative from a writer friend of Ben's, assembling his narrative from Ben's papers after the fact. So inside this frame we have a mixture of third-person narration, with one scene in second person, and first-person journal entries. Cinema is a largely third-person medium and the film removes the frame, telling the story in chronological order. Some plot elements are removed, such as an affair between Ben and Melanie, which leads to his blackmail. Susan's opposition to her husband's activities, her attitudes deriving from her family background, is reduced but still present. The story is a downbeat one, an angry one at a situation which was current when the novel was published and still current when the film was made, but the film adds a couple of final scenes, one of which raised a big cheer from the audience when I first saw the film, at the 1989 London Film Festival.

Other anti-apartheid films of the time included Cry Freedom (1987), directed by Richard Attenborough, and A World Apart (1988), the directorial debut of Chris Menges. For all these films' qualities – and I'd certainly suggest that in particular A World Apart certainly deserves attention – there is something polite and well-meaning about them, both the work of politically liberal non-South African white directors. A Dry White Season might, like Cry Freedom, centre on a white man's awakening to the situation around him, but it's not polite at all, with some graphic scenes of violence and police torture, not to mention a fair amount of racist dialogue on the soundtrack. While there's no reason why someone can't make films not based on their own experiences, having a director of colour on board makes A Dry White Season a very angry film. It feels personal.

Euzhan Palcy was born in 1958 in the French overseas départment of Martinique. She wanted to be a filmmaker from the age of ten, taking issue with the portrayals of black people on the large or small screens. She went to film school in Paris where she was mentored by François Truffaut. Her first feature film, Rue Cases-Nègres (released as Sugar Cane Alley in the USA and Black Shack Alley in the UK, 1983), was set on her home island. It won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival and the César for Best First Feature Film. As a result, Robert Redford invited her to attend the Sundance Director's Lab in 1984.

Palcy went undercover to South Africa, at considerable personal risk, to research A Dry White Season and ensure its accuracy. This involved visits to the people of Soweto township, some of whom had witnessed the riots dramatised in the film. As with the Attenborough and Menges films mentioned above, there was no question of A Dry White Season, a $9 million production, being made in South Africa itself. So all three films were actually shot in Zimbabwe. Sets were closed and Palcy and producer Paula Weinstein had personal security for the duration of their stay in the country. Interiors were shot in the UK at Pinewood Studios.

A mixture of nationalities played the white South Africans – Janet Suzman is the one principal to have been born in the country - and it's a tribute to the film how well integrated they are, with their accents sounding convincing enough to these British ears. Palcy was insistent on casting actual South Africans in the black roles, although this was at some considerable risk. Fake contracts had to be produced – for a non-existent stage production in London – so that they could leave the country and then fly secretly to Zimbabwe for the location shoot. These actors include Zakes Mokae (who had lived outside South Africa since 1961), Winston Ntshona and John Kani. The latter two had frequently worked together, often with playwright Athol Fugard, in particular in the play Sizwe Bansi is Dead, from 1972. They often clashed with the apartheid regime, and in 1976 (the year A Dry White Season is set) had been imprisoned in solitary confinement for fifteen days.

A notable member of the cast was Marlon Brando, who with this film returned to the screen after a gap of nine years, working for scale due to his commitment to the project. The section of the film in which he appears is much expanded from its equivalent in the novel and does risk feeling like it is part of a different film, as Ian McKenzie (Brando), a civil rights lawyer who takes on the case Ben brings to him, attempts to uncover the truth of Gordon's imprisonment and death but fails in an obviously rigged trial. This role earned Brando his eighth and final Oscar nomination, as Best Supporting Actor.

A Dry White Season was initially banned in South Africa, the censors claiming that it would impair President de Klerk's goals of apartheid reform. However, the ban was lifted a few months later, and the film was publicly shown in the country. It was mostly a critical success but not a commercial one, earning about a third of its budget in the USA. Palcy's only subsequent cinema film was Siméon (1992), a musical fantasy made in France. It wasn't released in the UK and I have not seen it. She has since worked on television, including "Ruby Bridges", a 1998 episode of The Wonderful World of Disney.

A Dry White Season is released by the BFI on a Region B Blu-ray. The film had a 15 certificate in cinemas and it retains that for homeviewing. Jemima + Johnny and The Burning both had U certificates on their original releases but are now PG. The BFI has attached advisory captions to the main feature and the two shorts indicating that they all contain racist language and, in the case of A Dry White Season, racist violence as well.

The film was shot in 35mm colour, the work of two cinematographers, Kelvin Pike and Pierre-William Glenn. The Blu-ray transfer is in the correct ratio of 1.85:1 and is as supplied to the BFI in HD by MGM. The colours are true, with strong blacks and shadow detail, and natural, filmlike grain. Jemima + Johnny and The Burning, both shot in black and white, 16mm and 35mm respectively, are presented in 1.33:1.

The soundtrack is LPCM 2.0, which plays in surround, reflecting the Dolby Stereo soundtrack with which the film played in cinemas. The surrounds are used for music, with several cuts from Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and directional sounds in some of the larger-scale scenes such as the Soweto Uprising near the start. The film is mostly in English, with some snatches of Afrikaans and Zulu intentionally left untranslated. Hard-of-hearing subtitles are available for the main feature and the two short films, and I didn't detect any errors in them.

Euzhan Palcy introduction and Q&A (36:08)

A Dry White Season premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on 10 September 1989 and thirty years to the day later, Euzhan Palcy returned to introduce a showing. Interviewer Lydia Ogwang tells us that the same cinema would be showing the film again in the future, as part of a Palcy retrospective. Following the film, Palcy returns for a Q & A, though if there were questions from the audience they aren't included in this recording. She has plenty to say, and Ogwang mostly lets her say it. Palcy pays tribute to her two "godfathers" (François Truffaut and Robert Redford) and talks about the importance of the film to her, and the fraught and sometimes dangerous conditions in which it was made. She also talks about how, in Rue Cases-Nègres, she tried to create a Martinican cinema, one which had barely existed before. In her future career she has faced opposition, being told that black stories, and especially black female stories, are not bankable, and she turned down many scripts which told white stories. "I don't want to do your stories as you don't want to do mine."

André Brink interview (19:15)

Filmed in 1990, Brink talks to camera (the interviewer was Peter Davis), with each section marked by a caption. His political awakening began when he was a student in Paris, and met black people which he had not done at home. His activism, and the genesis of A Dry White Season the novel, began with the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre of protestors and following deaths in detention. As a writer, his clashes with authority began with the banning of his novel Looking on Darkness, the first Afrikaans novel (Kennis van die aand) to be banned by the South African government. Brink then translated the novel into English and had it published abroad, and he then wrote in English from then on to reach a wider market. As a result, he was followed by the security forces and once had his novel notes and typewriter confiscated.

Brink comments on the filming of A Dry White Season and suggests that the then recent anti-apartheid films from outside South Africa enabled filmmakers to deal with racial issues at a safe distance, given that they rarely tackled racial inequalities in their own country. He was not involved in the writing of the film and found out about the altered ending when he saw it. He finds it a little glib, but understands the reason for it, and appreciated the importance of having a black director (and a black female director) making the film. He ends by hoping that South Africa could get beyond simplistic statements and work to a positive future for the country.

Jemima + Johnny (30:16)

Made in 1966 – not 1996 as the booklet has it, at least in the PDF version received for review – and shot in black and white 16mm, Jemima + Johnny (often referred to as Jemima and Johnny, but it's a plus sign on screen) takes place in Notting Hill. This was an area of London marked by racial tensions, which had led to the race riots of 1958. Due to deprivation, racial prejudice thrived and we see a leaflet from the White Tenants' Association saying "Beware! Black Menace. Protect your Neighbourhood." Five-year-old Johnny (Patrick Hatfield), the son of a white nationalist, befriends Jemima, the similarly-aged daughter of a newly-arrived Jamaican family. The film follows their adventures during a day, with little dialogue (the two central characters aren't actually named on screen, except in the credits) and a music score dominated by a guitar played by composer Bill Bramwell. While its message is clear – the conflict between parents not being inherited by their children, with some reconciliation implied by the events of the film's climax – it's conveyed without being heavy-handed.

The film was written and directed by South African-born Lionel Ngakane, who had been in exile from his home country since the 1950s. He wouldn't return until after the abolition of apartheid. Jemima + Johnny won a prize at Venice in 1966, making it the first black British film to win a festival award. Ngakane didn't direct again, though he worked as an actor and was a technical advisor on A Dry White Season. There's another link to the main feature in the appearance of Zakes Mokae as a blind man crossing the road.

The Burning (32:11)

The Burning (copyrighted 1967 but released in 1968) was Stephen Frears's first film as director. He had worked with Albert Finney on Charlie Bubbles as his assistant and it was Finney's company, Memorial Pictures, which financed the film, with Finney acting as uncredited producer. The film, shot in black and white 35mm, is based on stories by Roland Starke, who gets a prominent "by" credit at the start. Although it is set in apartheid-era South Africa, actually shooting there would have been as impossible then as it was for A Dry White Season over two decades later, so production took place in Tangier on a budget of £10,000.

Raymond (Mark Baillie) lives with his grandmother (Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies), their "Cape Coloured" chauffeur (Cosmo Pieterse) and their cook (Isabel Muller). Through Raymond's eyes we see the distinctions between the races: whites, the "Cape Coloured" and the black South Africans, and how they insist on those separations. Raymond becomes aware of his own casual racism and the film ends in tragedy. The Burning is a subtle, accomplished piece of work, the first of many of Frears's films tackling themes of social injustice.

Booklet

The BFI's booklet, available in the first pressing only of this release, runs to twenty-four pages. It begins with an essay by Kevin Le Gendre, which has a spoiler warning attached. He begins by describing a press photo of the Soweto Uprising, of a man holding his dead twelve-year-old son while his daughter screams nearby, which the film reproduces in a newspaper headline. Le Gendre locates the film of Brink's then decade-old novel at a time when international pressure against apartheid had been mounting, and singles like Artists United Against Apartheid's "Sun City" and The Special AKA's "Free Nelson Mandela" had been in the charts. While the story centres on a white man's political awakening, Le Gendre rightly emphasises the work of the black members of the cast, and the importance to Euzhan Palcy that she was giving a voice to genuine black South Africans rather than importing African-Americans to play the roles. He also discusses Susan's view of events, as played by Janet Suzman, who had grown up in Johannesburg and whose mother had been a civil rights activist. She sees black-white relations as a war, and takes as gospel the founding story of the nation, founded by Dutch Boer settlers who had fought the British for possession of the land and effectively wrote their own origin story, erasing the indigenous population in the process. Dissidents were labelled as terrorists and Communists. And while the situation shown in the film is no longer, in present-day South Africa there are still inequalities between black and white and nationalism is prevalent.

After a cast and credits list for A Dry White Season, there are notes on and credits for the extras, including long notes by Ellen Cheshire on Jemima + Johnny and The Burning.

Thirty-five years ago, A Dry White Season was a powerful, urgent film about the workings of the apartheid regime in South Africa. Now, with that regime no longer in existence, the film has lost none of its power, and while it was a period piece at the time and is even more so now, it has lost none of its relevance. It is presented well on this BFI Blu-ray, with a couple of excellent shorts among the extras.

|