|

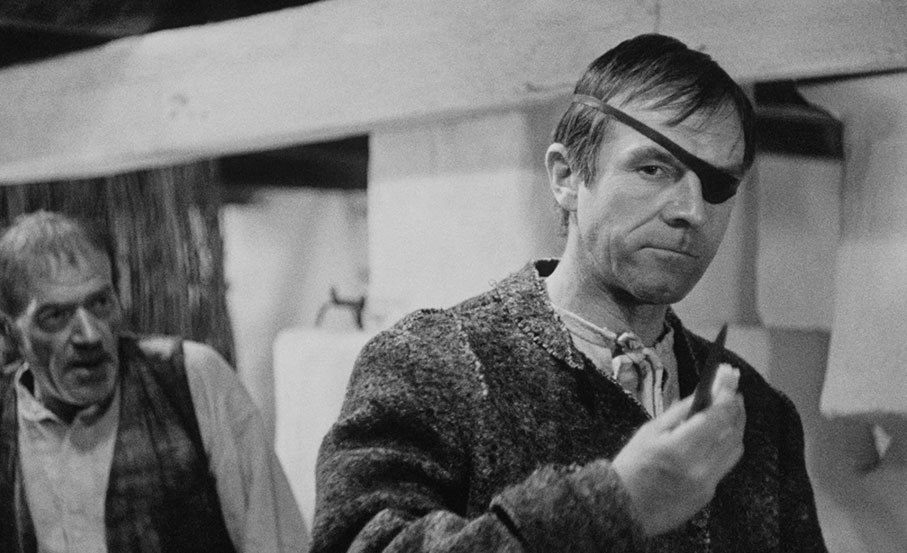

I love being deliberately and successfully misdirected by a film, particularly if it's done with the sort of purpose and artistry as you'll find in the compelling first half of Eduard Grečner's extraordinary 1968 Dragon's Return [Drak sa vracia]. The film begins with a portentously scored circular pan of a remote mountainous region during a deliberately unspecified period in history, concluding just as a lone male figure (Radovan Lukavský) drifts into frame. Dwarfed by the landscape, he has his back to us and is standing next to the twisted remains of a tree that may or may not be an expressionist pointer to past events or those to come. The unsettling music continues as the location shifts to show a woman (Emília Vásáryová) preparing a meal in her white-walled home, then pausing her actions and seeming to sense something, a presence, perhaps, a troubling but unspecified disruption to her everyday norm. As if responding directly to the woman's curious glance, the figure seen briefly in that opening shot turns to a reveal a stern and weather-beaten face, one sporting a black eye-patch and a livid facial scar. It's a countenance that seems to ooze trouble from every pore. What has actually prompted him to turn his head is local man Zachar, who has just rolled up on the back of a horse-drawn cart and has paused to offer this traveller a lift to the village situated at the foot of the mountain. "Don't you recognise me?" the scar-faced man asks. Zachar clearly does and belts off towards the village at a frantic gallop. "Dragon's back!" he shouts as a warning on his arrival. Pandemonium ensues. "Dark days are coming!" one woman cries, "Dragon's back!" If you weren't already convinced of the scar-faced man's malevolent purpose, the fact that he's named after a mythical, fire-breathing reptilian monster should seal the deal.

By the time Dragon arrives in the village under his own steam, the local menfolk are gathered in the pub and debating what to do about his worrying return. "It's Šimon's business," one man suggests. A short while later the Šimon (Gustáv Valach) in question returns home to Eva, the woman we saw preparing a meal in the opening scene. She serves him food, but he is unable to eat it. Neither she nor he seem remotely comfortable in each other's presence – they make no eye contact, and no words pass between them until Šimon gets up to leave. "He's come back for you," he tells the woman we presume is his wife. "Dragon is back."

The conviction that Dragon is a bitter avenger with a terrible past who is biding his time before unleashing who knows what on these peaceable locals is enhanced when he walks into the pub and all conversation immediately ceases. He walks up to the bar, swallows a couple of drinks, chews briefly on some food (which he imposingly cuts with a suddenly produced flick knife) and silently departs. From the moment he leaves he is the topic of fevered conversation. Just what is going on here? Not, it turns out, what the film has used our own convention-formed preconceptions to lead us to suspect.

Here's where it gets a little tricky for me, as to say much more would involve delivering an unfair sprinkling of spoilers. The gradual unfolding of the truth, primarily through a series of hauntingly executed and precisely positioned flashbacks, constitutes one of the film's principal pleasures, as they force us to re-evaluate everything we've seen and re-examine how and why we found it so easy to interpret events and characters the way that we did. But this does make it difficult for me to comment on what happens in the film's second half without discussing plot points that should ideally not be revealed in advance. What I will say is that it consists of a long and arduous journey undertaken by Dragon and the aforementioned Šimon, one in which we are again invited to be distrustful of Dragon's true intentions. By this point, however, we are better positioned to comprehend and more accurately interpret his actions than the suspicious, prejudicial and vindictive Šimon.

A morality tale, then. Well, in a way yes, but director Eduard Grečner is neither preaching nor attempting to highlight the obvious, and instead uses this lesson in the still pertinent dangers of prejudicial ignorance and the mob mentality as the basis for a work of consistently mesmerising audio-visual poetry. Crucial to this is the astonishing experimentalist score by Ilja Zeljenka, who also provided the memorably unsettling music for Stefan Uher's The Sun in a Net (on which Grečner was assistant director). As unconventional and operatically haunting as Popol Vuh's famously dreamlike music for Werner Herzog's Aguirre, the Wrath of God, it has a transformative effect on the action it underscores, infusing even the calmest scenes with a discomforting sense of almost apocalyptic and even alien menace, and landscapes with an air of sometimes spiritual wonder. So wedded is the music to the visuals that, as Jonathan Owen highlights in the accompanying booklet, there are times when the score and the sound effects seem to meld into each other, and others when one element of the soundtrack becomes so purposefully dominant that all other sound (and occasionally all sound) is pushed into silence. Intermittently, I couldn't help but suspect the influence of Hungarian avant-garde composer Györgi Ligeti (this may be purely coincidental, of course), and there are elements here that I'd swear made their way into the tribal themes of John Corigliano's work on Ken Russell's Altered States.

Visually, the film is consistently arresting, with Grečner making telling use of cinematographer Vincent Rosinec's sometimes breathtaking wide shots to bring home the role that the surrounding mountains play in shaping the lives and the destinies of those who live in their shadow. But what really hits home here is the manner in which Rosinec frames the characters, from the follow pans of Dragon, Šimon or Eva as they move through the village, the landscape or the interiors of buildings, to the telling close-ups employed to capture their emotional responses or focus our attention on objects whose relevance only becomes clear through the passing of time. Most memorable of all is a handsomely executed flashback shot that sweeps up to and around Dragon and Eva, an emotive camera movement that is later repeated in modified form with different participants to powerful effect, coming to rest as the distant and indistinct figure of Dragon slips tellingly into frame. Sorry, but you'll need to see the film to understand why this delivers such a kick.

The work of editor Bedrich Voderka (another The Sun in a Net alumnus) is equally important to the storytelling and substructure, aiding Grečner in his early character misdirection, economically expanding on character detail and forging implicit links between Dragon and Eva from an early stage. Repeatedly, the two appear to turn and look at each other despite their locational distance, a technique that suggests an almost telepathic bond but later feels triggered more by deeply ingrained memories. Elsewhere, a combination of imagery, sound and a single edit is employed to subtly suggest a link between the pagan rituals of female villager elders, the roaring fire of Dragon's kiln, and the burning forest in which the village's cowherd is trapped.

Dragon's Return (and I can't emphasise enough how much I prefer that translation to the stiffly formal alternative, The Return of Dragon) is a beautifully handled and quietly compelling example of why 1960s Czech and Slovak cinema remains one of the major epicentres of film creativity of that day. This was my first exposure to the work of Eduard Grečner, and when I first watched it back in 2015, I was so captivated by it that I was drawn back to it repeatedly in the days that followed. Each time I drew something new from the film and saw specific elements in a different light – I was three viewings in before it struck me that it also played as a still too-relevant story of a creative mind ostracised by a community swathed in superstition and ignorance. My reluctance to specifically discuss aspects of the film for fear of spoiling things for newcomers means that I've only scratched (and dug a little bit below) the surface of what this remarkable work has to offer. Fans of 60s Slovak cinema should need no further persuading, and for those of you who have yet to experience its varied and often thrilling delights, this is an excellent place to start.

The 1080p transfer on Second Run’s new Blu-ray is – and I quote – “presented from an HD transfer of the new 2K restoration of the film by the Slovak Film Institute.” I’m not in a position to say just how new this restoration is, but the SD transfer on Second Run’s 2015 DVD was also presented from a high-definition restoration, and while the source was not specified there, the Slovak Film Institute was thanked in the accompanying booklet for making the release possible. I mention this only because it does look as if this new transfer was sourced from the same restoration, exhibiting as it does the same strengths, as well as the same minor flaws – a variance in picture sharpness and some slight brightness flickering – that I’m again going to chalk up to weaknesses in the material from which the restoration was made. Where it visibly improves on the SD transfer is, as you’d expect, in clearer and crisper definition of the picture detail, though this is more evident in some shots than others. Another improvement is in the contrast range, which feels a little more generous here, resulting in improved shadow detail throughout. On the whole, a solid job, and a definite upgrade on its SD predecessor.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack does have the inevitable range restrictions, which are most evident on the dialogue, but there’s a finesse and clarity to the music and sound effects that lifts this a good couple of notches above the Dolby track on its DVD predecessor. Given the importance of both elements to the tone of the film, this is most welcome, and as with the DVD track, there are no obvious signs of wear or background hiss or fluff.

Clearly rendered optional English subtitles are available and kick on by default when you play the film.

An introduction to the film by Rastislav Steranka (5:23)

Rastislav Steranka of the Slovak Film Institute provides some interesting background on director Eduard Grečner and his approach to what he rather poetically once described as “introverted reality.” This leads naturally to a discussion of Dragon’s Return, including some interesting comments on Ilja Zeljenka’s extraordinary score.

Peter Hames on Dragon’s Return (23:14)

The author of The Czechoslovak New Wave provides a concise introduction to Czech and Slovak New Wave cinema and the career of director Eduard Grečner, before focussing more specifically on Dragon's Return. His analysis of the film's many qualities is detailed and perceptive, with specific coverage of the music score, the camerawork, the film's intriguing blend of folklore and modernism, and more. When I first watched this on the film’s DVD release, I was kicking myself for not picking up of the parallels with American westerns and particularly The Searchers, and was interested to hear that this is widely regarded as Grečner's best film. Grečner's contribution to The Sun in a Net is also touched on here. There are no real spoilers, but clips from the film's final scene are included.

Dragon’s Return Documentary (19:23)

A production for the Slovak Film Institute, this new documentary on Dragon’s Return includes interviews with film and literary historian Jelena Paštéková, fine arts theoretician Juraj Mojžiš, film historian Eva Filová, and best of all, the film’s director Eduard Grečner, who by my calculation must have been a sprightly 91 years of age when this was filmed. There are plenty of extracts from the film and the interviews are crisply shot in monochrome HD, though edited in that annoyingly two-angle ping-pong style that seems to be in fashion at the moment. Grečner recalls first encountering Dobroslav Chrobak’s novel and his desire to turn it into a film, and talks about the themes, the story and the set design; Paštéková also gets under the skin of the narrative and discusses the 60s Czech filmmakers’ obsession with truth; Mojžiš ruminates on the film’s meanings, its gender roles and the notion of silence as a form of oppression. Grečner also talks about Ilja Zeljenka’s music score – “Some say that the music is the most beautiful part of the film,” he notes, then adding, “I entirely agree with that,” before going on to explain why.

Booklet

The included booklet is for the most part the same as the one that accompanied the 2015 DVD release, but I’ve absolutely no problem with that. Leading the way is a detailed and engrossing essay on director Eduard Grečner, one that leaves my piece above looking seriously anaemic, though be warned, it does include some major spoilers (the whole plot is laid out, including the ending), so I'd save this until after you've watched the film; you'll get more from it then anyway. This is followed by an interview with Grečner conducted by Jonathan Owen, which provides some welcome insight into the director's intentions for the film and helps confirm a few things that might otherwise remain the subject of critical speculation.

What impressed the hell out of me when I first saw Dragon’s Return in 2015 continues to do so seven years later. It’s a compellingly told tale, gorgeously directed by Eduard Grečner and boasting strong performances all round and an extraordinary score by Ilja Zeljenka. The HD transfer on Second Run’s Blu-ray is a definite step up from the 2015 DVD, and the special features have been pleasingly expanded. If you have the DVD, it’s definitely worth the upgrade, but if you’ve never seen the film and have even a passing interest in Eastern European cinema, this is a must. Highly recommended.

|