| |

"Men just aren't the same today"

I hear ev'ry mother say

They just don't appreciate that you get tired

They're so hard to satisfy

You could tranquilize your mind

So go running for the shelter of a mother's little helper

And four help you through the night

Help to minimize your plight |

| |

Mother’s Little Helper – The Rolling Stones, 1966 |

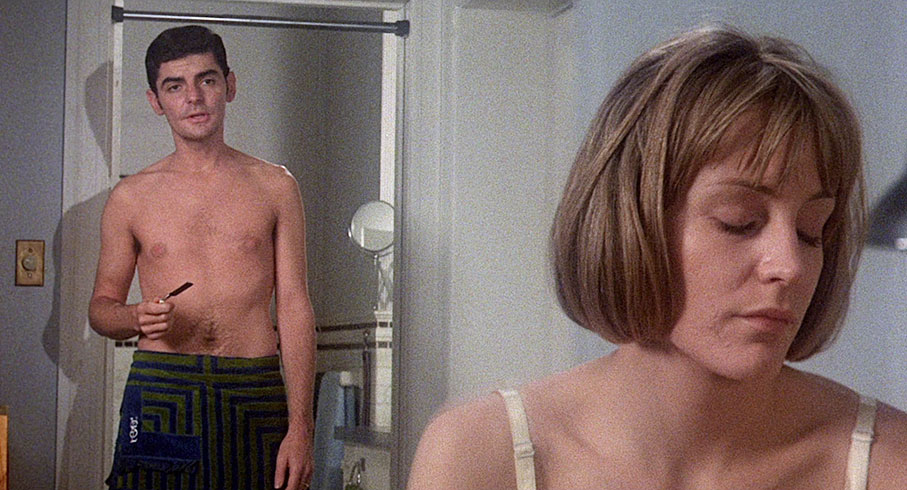

Tina Balser (Carrie Snodgress) leads a thankless and unfulfilling life. Her husband Jonathan (Richard Benjamin) is a successful corporate lawyer, and the two live in a spacious and well-appointed New York apartment with their two young daughters Sylvie (Lorraine Cullen) and Liz (Frannie Michel). But Jonathan is also a self-centred, supercilious arse of the first order who misses no opportunity to belittle his wife. As the film begins, Tina is woken by Jonathan’s off-key singing as he prepares to shave, and is immediately told irritably by him to get out of bed. As she sleepily rises, her husband wonders out loud what the matter is with her these days. “You don’t look well,” he tells her. “Your colour’s rotten. You act as if you’re exhausted. How could you be exhausted the minute you get up in the morning?” As she pulls off her nightgown, he criticises her body. “You used to have a terrific figure,” he tells her, “but now you’ve got so bloody skinny. And that godawful hair of yours. Just… hanging down. No style.” Maybe she doesn’t care what she looks like in front of him and their daughters, he suggests, but what about the rest of the world? “You’re Mrs Jonathan Balser,” he reminds her. “My wife! My wife is a reflection of me.” He claims to be only telling her this because he’s concerned about her, and when she lights up a cigarette, he picks on her for that too. Do you know what you’re doing to your lungs, your heart, your circulatory system? Tina simply shuffles to the ensuite bathroom, slowly and silently nodding.

The foundations for the whole film are laid out in this opening scene. Everything about Jonathan’s snippy critique suggests that this is not some first-time expression of concern for his wife’s wellbeing but part of a daily ritual of belittling verbal darts thrown in her direction. It doesn’t end there. When he takes the top off of his boiled egg at breakfast, it’s time to criticise Tina for her inability to properly cook a four-minute egg. This time he smilingly mocks her shortcomings to Sylvie and Liz, who listen to his words in compliant silence. He then indicates some nearby travel cases and says to his daughters with a sigh, “Oh, will you look at those trunks. Back from the country over two weeks. She hasn’t unpacked those bloody trunks yet.” Again the daughters do not verbally respond, which I initially I suspected was because they were also verbally bullied by their father and silently sympathetic to their mother’s plight. Boy, was I to be proved wrong on that one. No sooner has the busy Tina returned to the dining room than Jonathan is asking for more toast, and as she jogs back to the kitchen he suggests loudly that she get cracking on a full housecleaning campaign. When the toast arrives, he complains that it’s too light, and just as Tina tries to grab a sip of coffee, he’s asking her for a little more damson plum reserve. Her disbelieving pause before flashing an insincere smile and trotting back to the kitchen for the umpteenth time speaks volumes.

Viewed retrospectively, it would be a little too easy to see this as a little heavy-handed, but to do so would require turning a blind eye to the social norms of the time and the society in which this film was made. As is noted in the special features on this disc, in 1950s America the aspirational norm for young middle class women was not that they would pursue to a career, but that they should marry a rich doctor or lawyer and be a devoted wife, a good mother, and an industrious homemaker. By the late 1960s, things were changing. Those in the counterculture movement were rejecting the values of the previous generation, and feminism’s second wave was directly challenging the unequal treatment of women at all levels of society. The long-established image of the American housewife (who, as Marge Simpson once cannily noted, is not married to a house) as a happy and willing domestic who lives to serve her husband and her two perfect children was starting to crumble. That many middle class housewives were secretly turning to alcohol and Valium to numb the pain of a dull, unfulfilling and even depressing existence is what inspired Keith Richards and Mick Jagger to write the song quoted at the top of this review. But it too rarely got openly discussed or admitted to. We have to keep up appearances, don’t we, my dear. Remember Jonathan’s early morning words to Tina? “My wife is a reflection of me.” Diary of a Mad Housewife does not just touch on this issue, it makes it its central theme.

The film was the final collaboration between husband-and-wife team of Eleanor and Frank Perry, being directed by Frank and adapted by Eleanor from the novel by Sue Kaufman, one that was apparently dear to the hearts and past experiences of both women. And while years of subsequent realist domestic dramas and soap operas can make Jonathan’s verbal bullying of Tina feel a little like the carefully written dialogue it essentially is, there is a very real truth at its core that ensures these scenes remain genuinely uncomfortable to watch. Everyone who’s seen the film will remember the sequence when Jonathan is lying ill in bed and screaming “TINA!” every few seconds to make petty demands, or his sleazily delivered requests for “a little old roll in the hay.” He also repeatedly and sometimes angrily berates her for not lifting a finger to help with domestic or social arrangements that she has been working her guts out behind the scenes to ensure run smoothly on the day. Seriously, I lost count of the number of times I wanted to see Tina slam her foot into Jonathan’s goolies, grab her things, and get the hell out of that apartment.

Perhaps even more insidious is the way Jonathan repeatedly belittles Tina in front of their daughters, which here doesn’t traumatise the girls as you might expect but instead encourages imitation and installs in them the same level of callous disrespect for their mother. Worst of all by some distance is Sylvie, an insufferable little shit whose first words in the film come when she and her sister arrive home with Tina to discover that their dog has taken a dump on the carpet, prompting Sylvie to bark loudly at Tina, “You bloody well better clean that up before Daddy gets home!” It’s a telling moment, one that sees Tina and her daughter exchange places in the accepted hierarchy of family authority, and Sylvie emulate her father’s behaviour towards Tina and even employ his favourite swear word as a tool of admonishment. It won’t be the last time. Later, Sylvie expresses her disgust at her mother’s outfit because it’s “cut so low your breasts are hanging out” (they aren’t), and complains about the odours emanating from the Thanksgiving meal that Tina is slavishly preparing (“You can smell the bloody onions all the way out to the bedroom!”). During the meal itself, she spits out the stuffing in disgust and bellows angrily that she likes oysters “on the half shell with cocktail sauce, not in the bloody turkey, for God’s sake!” before dismissing the whole meal as awful. Even Jonathan puts his foot down at this, a rare time when he comes to Tina’s defence.

It's doubtless her unhappiness at this relentless verbal assault that is behind Tina’s early morning tiredness (seriously, ever worked in a terrible job and struggled to get up and face the day?), as well as her secretive daytime drinking, an aspect of the film that is handled with commendable subtlety and never overstated. It also pushes her into an affair with playboy novelist George Prager (Frank Langella), a narcissistic user of women who, in his way, is every bit as arrogant and unpleasant as Jonathan. It’s a relationship in which Tina finds a degree of sexual satisfaction and release, but in which she is mocked and at one point violently pushed around by a man who sees her as little more than – in his own words – “a terrific piece of ass.” It’s clear that Tina deserves so much better, but the opportunity that is genuinely right for her just never seems to come knocking.

If the initial impact of the film has been blunted just a little by the passing of time and some of the harder-hitting tales of domestic misery and abuse that have followed in its wake, Diary of a Mad Housewife still holds its own on the strength of its writing, its direction, and its lead performances. You may want to slap Jonathan – I certainly did – but a key reason for this is Richard Benjamin’s portrayal. Fastidious about his appearance and social standing but contemptuous of a woman we can at least presume he once loved and perhaps even respected, he delivers many of his put-downs with a condescending smile, as if he’s pointing out what he believes should be obvious to the slowest child in class. That he is always trying to cosy up to more prominent and successful figures in the New York society scene of the day also suggests that beneath this over-confident surface bluster lies a deeply insecure man, one who is, in his own pathetic way, every bit as lonely as Tina. That said, he’s given a run for his money by Frank Langella, who plays George with discomfortingly believable blend of easy charm and smug self-satisfaction. For him, women are on the planet solely to service his sexual needs, and all are ultimately interchangeable and ultimately disposable, another very male front behind which to hide deep insecurities, ones that Tina eventually recognises and exposes to his face.

But the real star of the show here is Carrie Snodgress, whose performance as Tina is a masterclass in restrained frustration and suppressed torment, communicating so much with just a look, a pause, the tone of her voice or her body language (just watch her face when she realises that Jonathan will fall victim to an illness that has already infected the children). On the rare occasions when she does lose her rag, the fire in her eyes, her expression and her words confirm the underlying strength of a woman who has been slowly drained of any traces of dreams she may have once had for a life that seems to have long since escaped her. Initially, she seems to come alive in George’s company, but soon comes to realise that she has ultimately exchanged one form of abuse for another. Watch the film once for its characters, its dialogue and its story, and then watch it again just for Snodgress’s performance, and note how many brilliant little things she does that tell you about Tina’s life and her state of mind. It’s no surprise that this role won her a Golden Globe and saw her nominated for the Best Actress Oscar, where she was unfortunate enough to be up against Glenda Jackson in Women in Love.

There’s never a sense with Diary of a Mad Housewife that we’re watching a neorealist work, but director Frank Perry still avoids some of the more traditional flourishes of confrontational filmed drama. Camera movements are limited, overly expressive (or perhaps expressionistic) angles are avoided, and cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld – who also shot Richard Benjamin’s 1969 debut feature, Goodbye, Columbus – gives the domestic interiors a naturalistic flatness, employing backlight to subtly soften and beautify Tina’s visits to George’s riverside apartment. Only in the sequence set in Elaine’s restaurant (once the New York in-crowd place to eat) and the party at which the Alice Cooper Band are playing (for real) is he free to deviate from this brief, using coloured gels and more stylised lighting to reflect the atmosphere of the venues and differentiate them from the world to which Tina is generally confined. The grounding of the drama in reality extends to the absence of a traditional score, with the only music heard being diegetic to the scene in question.

The true strengths of Diary of a Mad Housewife only really become evident when you view it in the context of when it was made, but even if you put that aside – and you really shouldn’t – it still shines in its lead performances, its screenplay, and its consistently confident handling. Yes, a couple of the supporting roles teeter on caricature (the complaining, middle-aged Jewish babysitter played by Lee Addoms could almost be out of a Mel Brooks movie), and there are occasions when it feels as if the camera is almost as fascinated as George by Tina’s body, although for the most part what nudity there is feels refreshingly natural to the scene in which it appears. The title comes under some scrutiny in the special features, with particular emphasis on how the film interprets the word ‘Mad’, but a more intriguing take was proffered by Roger Ebert, who suggested that the use of the word ‘Diary’ might suggest that events and characters are being presented exclusively as Tina sees and experiences them. It’s an interesting theory to throw into the analytical mix for an important, well-crafted and compellingly acted film, one whose final two scenes – which I’m not about to spoil by divulging – are both worthy of a few paragraphs of analysis and speculation alone.

Framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, the 1080p transfer on Indicator’s Blu-ray was sourced from a Universal HD remaster. The first thing to note is that the film grain is very visible, but this is clearly not as the result of any digital enhancement, but likely due either to the film being shot on high-speed film stock or remastered from an interpositive rather than the original negative. Without specific details, I can’t be sure, but it feels very film-like and organic to the image. In all other respects, this is a fine transfer, with clearly defined detail and well-balanced contrast, and while the film’s toned-down colour scheme is faithfully reproduced, when brighter colours do appear – a yellow taxi cab, the lighting in the party scene – they really pop. As expected, the image is clean with no movement in frame.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack has also been remastered and is clean of any traces of wear, with dialogue, effects and diegetic music always clear, albeit within the normal range restrictions of the day.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Alternative TV Version

Now this is interesting. This version, which includes a large textual admission that it was ‘Edited for Television’, is not just the cinema release with the more adult content trimmed, but one that differs substantially from the theatrical original and is five minutes shorter. The cuts are there, a lot of them as it happens, but there is also a surprising amount of new material that was clearly shot by Perrys but omitted from the cinema release. Although this material was clearly added to pad out the running time and bring the film back to feature length after the material deemed unsuitable for American television of the day had been removed, it also tells us more about Tina, her relationship with her unpleasant daughter Sylvie, and even a few of the minor supporting characters. That’s me being kind, as in the process of doing so, it also overstates what is inferred in the film and takes the edge of a couple of scenes by conventionalising them.

I’ll confess to not knowing the film on a shot-by-shot basis, and I didn’t have time to load both versions into editing software to do a precise side-by-side comparison of the sort I have occasionally done before when presented with alternative cuts of the same film. That said, I did watch the TV cut shortly after watching the theatrical original, and whilst doing so jotted down some of the changes that immediately struck me, which I’ve listed below. The alterations do reveal something about the strictness of the TV censorship of the day, though also include one contradictory oddity, which I’ll get to below. There are obviously going to be some spoilers for both cuts of the film here, and if you want to avoid them, or have better things to do with your time than read lengthy lists, then skip to the paragraph at the end of the bullet points below, or simply click here.

- The theatrical cut’s opening scene and title sequence have had their order reversed so that the title montage now plays before the one in which Tina wakes and is berated by Jonathan. This will later be shown to make no storytelling sense.

- All nudity and vocal references to Tina’s body in the (now) post-title scene have been removed.

- The bathroom sequence that follows runs for a few seconds longer.

- After Tina has seen the girls picked up for school, a new sequence has been added showing her walking the family dog and reacting to what she thinks is a dead man lying in the street, but that turns out to be a sleeping transient.

- Immediately after seeing the transient, Tina loses the dog in a park and finds it being petted by a seriously creepy man, who stares at Tina with leering intent but who runs off when another dog walker appears.

- This is followed, both in film and narrative terms, by a sequence in the apartment, where Tina pours herself a drink, then answers a call from Johnathan, who claims he’s been trying to reach her for half-an-hour. Tina tells him that she was nearly raped, but after showing some initial concern, Jonathan suggests she make another appointment with Dr Linstrom, who “straightened you out a few years ago,” a suggestion that prompts the irritated Tina to respond, “What the hell makes you think I need ‘straightening out’?”

- We then get the first of a series of brief flashbacks to Tina’s former therapy sessions with Dr Linstrom, who is viewed upside-down from the viewpoint of the laid-down Tina, an uncharacteristically gimmicky shot that Frank Perry was apparently unhappy with. These really overstate what is inferred in the theatrical cut, but do confirm that the issues that are troubling Tina go back several years.

- We then get a long sequence comprised of footage seen only briefly in the title montage, as various men and women arrive at the apartment to carry out a variety of cleaning and repair jobs, all of whom converse with Tina, who greets each of them at the door when they arrive. Almost all of this material is new to this cut, and it makes a nonsense of the new positioning of the title sequence, which is effectively a heavily compressed version of the same thing. The arrivals include black laundry woman Vera, who complains to Tina that she has to take care of her own domestic duties before attending to hers, and rolls her eyes when her employer specifies that some clothing items need to be hand washed. Next is a cartoon jobsworth of a cleaner, who tells Tina that despite what she may have booked with the agency, he doesn’t wash floors, then complains about the inadequate ladder she offers. When she remarks that she assumed he’d bring one with him, he replies, “You want me to bring a ladder, lady, you got to request a ladder.” Two building maintenance men knock at the door because water is leaking through the ceiling of the apartment downstairs, and they thus have to take a look at Tina’s shower. This does at least provide an explanation for why the two of them are shown chiselling off tiles in the title sequence, which here happens before they arrive at the apartment. One of them also gets into an argument with a delivery man about the use of the residents’ elevator, which is diffused by Tina just as it’s about to get physical. Finally, a cheerful elderly workman arrives to polish the floor.

- Midway through this montage is new sequence in which Tina is on the phone to her doctor, who assures her that he’s not going to prescribe tranquilisers or sleeping pills, and suggests that she get more exercise instead.

- At the tail end of the montage, Tina tells Vera that she’s going out, and is then shown looking at paintings in an art gallery. This is directly linked to another of the Dr Linstrom flashbacks, where he talks about finding meaning in “those little dibs and dobs all over your canvases” and the anger expressed in Tina’s paintings. It’s then confirmed that Tina originally wanted to be painter, a plot point not touched on in the theatrical cut.

- After Jonathan comes home unexpectedly in a foul mood because his plane had to make an emergency landing and orders her to contact the Willards and the Bards to arrange a dinner out, the sequence continues past where it ends in the theatrical cut. Tina now ambles over to Chinese food she bought for her dinner and starts contemplatively breaking open the fortune cookies and reading the fortunes with growing amusement. She then calls the Willards and the Bards, who reveal that they are getting ready for a meal out together and invite Tina and Jonathan to join them, an offer that Tina unexpectedly declines.

- When George approaches Tina at the party at which the Alice Cooper band is playing, his curt “Oh, that lying cunt” is missing that final word. He can still be seen saying it, but his voice is momentarily silenced as he does so. A second use of the word later in the film has also been excised. No surprises there.

- Jonathan’s requests for “a little old roll in the hay” are gone.

- The short sequence in which Tina and the girls arrive home and Sylvie yells at her mother about cleaning up the dogshit on the carpet has been removed.

- Much of Tina’s bedroom chat with Sylvie has been cut, with no mention here of boobs, breasts or vagina, while Sylvie’s angry complaint about their middle-aged babysitter, “I can’t stand Mrs Prince, she smells like a wet dog!” has also been removed.

- At the art gallery party, a couple of shots have been removed of semi-naked female mannequins, one of which is on all fours with a glass tabletop on its back, a piece of sexist human furniture that would not be out of place in Korova Milk Bar sequence in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange the following year.

- When George approaches Tina and mocks her for thinking he and his friend were laughing at her, her response – “Go to hell!” – has been clumsily redubbed with “you worm!”

- Other snips have been made to this conversation, removing the line “cut the crap” and George’s insinuation that Tina is becoming excited. His comment about something that hasn’t happened to him since he was a horny teenager, and him placing Tina’s hand on his erection are both gone, and the clumsiness of the resulting edit makes it clear that a cut of some sort has been made.

- Tina’s first visit to George’s apartment starts earlier here than it does in the theatrical cut. In this version we see her arriving, admiring the view of the East River once inside, and stepping out onto the balcony and noting all of the landmarks that she can see. George responds by trapping her on the balcony by closing the door, muttering a sarcastic “lucky me,” fixing himself a drink, and only letting Tina back inside when she knocks on the door.

- All of subsequent undressing and any hint of nakedness and lovemaking has gone, as has all of their post-coital conversation and the moment Tina angers George by insulting his books. Instead this version cuts straight from their first kiss to Tina putting her coat on to leave. That’s eight minutes of very relevant material chopped.

- At the family thanksgiving dinner, when Sylvie angrily complains about the stuffing and spits it out, the first part of a her furious response to Tina’s claim – that she likes oysters “on the half shell, not in the bloody turkey…” – remains, but the last part – “for God’s sake!” – is missing. To me, this is an odd one. Yes, we know that TV censors in America of the day were puritanical when it came to anything that might offend the Christian lobby, but they curiously seem fine with the repeated use of “bloody” as a curse word in the film. A friend of mine cannily suggested that that this might be because this particular adjective was not in common use as a swear word in 1970s America and was more commonly heard on this side of the Atlantic, where it would likely have been snipped for a TV screening.*

- When George says to Tina, “I suggest you just go to bed and relax,” the TV version doesn’t cut to her in bed with George as it does in the theatrical original, but straight to her lying in her own bed reading Marcel Proust’s The Past Recaptured, just before George drops his Christmas shopping list on the bed for her to action. The complete removal of this five minute assignation between Tina and George not only loses some revealing conversation between them, but suggests they see each other less frequently than they do.

- The naked, post-coital conversation between Tina and George that occurs after Jonathan has barked at her, “I would like to see you do one thing to make this party a success!” has been cut. The scene begins instead with Tina preparing to leave George’s apartment and telling him that she’s going to be busy for a while.

- When George gives Tina her a Christmas present, the scene now ends when she opens it and to find it contains a lacy chemise. The sequence that follows of her undressing and trying it on for George’s pleasure is has been removed, as has the sequence after this of the two in bed where George takes a phone call from what is clearly another girlfriend, and a row blows up between him and Tina.

- At the big party at the Balser apartment, the last part of the conversation between Tina and Charlotte, when Tina says, “I thought you got into the movies because you were Maddy Gordon’s favourite hooker,” has been cut, removing one of the only times that Tina bites back.

- When Tina visits George again, the sequence in which the two of them are naked in the shower, and conversing as they dry and dress has been removed.

- The subsequent scene fades out immediately after Tina throws a hairpin at George and angrily says, “Or is it some other broad that’s made you so puking tired?” The furious row that subsequently explodes between them, including George pushing Tina around and Tina’s fiery verbal response has been lost.

- A significant new scene has been added involving Tina, her daughters Sylvie and Elizabeth, and their maid Lottie. It kicks off with Lottie telling Tina that George has called, left his number, and asked her to call him back, and Sylvia behaving like the spoilt little shit she’s already been repeatedly shown to be. When she barks at Tina, “All right, all right, don’t get so bloody excited!” Tina slaps her face, which prompts Sylvia to yell, “I hate you!” and run from the room. Elizabeth reacts with similar hostility and runs over and hugs Lottie, who tells her she should apologise to her mother. Afterwards, Tina visits the crying Sylvie in her bedroom, and the conversation that unfolds between them lays things out somewhat literally and ends with a degree of mutual understanding between the two. As Justin Bozung points out on his commentary track, this puts a too-traditional Hollywood spin on a film that otherwise avoids easy answers. But of course, the Perrys did write and shoot this before rejecting it…

- After this, Tina looks contemplatively at the notepad on which Lottie has written George’s number before tearing it up. Again, this provides a degree of finality to a situation that is left teasingly (and far more effectively) ambiguous in the theatrical cut.

- The final scene – which I’ll avoid detailing here – has been recut to remove terms like “bastard,” “sexual intercourse” and “spoiled bitch.”

I’m sure there are more, but that’ll do for now, and should give a flavour of just how differently slanted this TV version is. If you watch and appreciate the theatrical cut, I’d definitely give this version a look, as it really does play differently to the original. Better, however, it most definitely is not. It should also be noted that this cut is presented in Standard Definition and is framed 4:3 (open matte, with slight cropping at both sides), having been mastered from an off-air recording captured to domestic VHS provided by the film’s assistant to the producer, Lydia Wilen.

Theatrical Cut Audio Commentary with Rutanya Alda and Lee Gambin

Film historian Lee Gambin and actor Rutanya Alda, who worked with director Frank Perry on the notorious Mommie Dearest, deliver a tightly crammed commentary packed with opinions on the film and information about it and its makers. Areas covered include original novel author Sue Kaufman, Eleanor and Frank Perry, actors Carrie Snodgress, Richard Benjamin and Frank Langella, the changing times and the rise of the Women’s Liberation movement, this film’s influence on later film and TV works, Elaine’s restaurant, the film’s telling penultimate scene, and much more. Gambin draws some fascinating parallels with Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, and although Alda seems to get her timeline a little mixed up here (she suggests that Polanski saw this film and borrowed from its imagery, but Rosemary’s Baby was made two years before Diary of a Mad Housewife), her anecdotes about working on Mommie Dearest, the details she provides about Sue Kaufman’s death, and her recollections of working as a Yellow Cab driver and nearly running over Rudolf Nureyev make for fascinating listening. Gambin has the microphone here, and appears to be talking to Alda via video conferencing on a phone or laptop, which results in her voice sounding far tinnier than his.

TV Version Audio Commentary with Justin Bozung

Frank Perry Biographer Justin Bozung kicks off his commentary by highlighting a few key differences between TV version and the theatrical release, making me wish I’d listened to this before writing out that overlong list of changes above. In the end he has too much to say about the film and its makers to identify or talk about most of the changes (I can’t deny that I was rather selfishly relieved by this), but does still pass comment on the more significant ones. Subjects covered include Frank Perry’s anger at this TV cut, how Eleanor being asked to review Sue Kaufman’s book for Life magazine eventually led to the making of this film, shooting the Alice Cooper party scene, the central performances, Frank Perry’s direction, how disenchantment with traditional gender roles fired the second wave of feminism, the social changes taking place in America in the 1960s, and much, much more. Bozung expands on an observation made briefly in the other commentary by directly comparing Langella’s role as George to his one as Dracula on stage and in John Badham’s 1979 film adaptation, and he makes a case for why the Perrys were undervalued when compared to their more widely championed contemporaries. A fascinating listen.

A Confident Approach: Richard Benjamin (5:44)

An extract from what was clearly a longer interview with actor and director Richard Benjamin, conducted in 2011 by Jeremy Kagan. Here Benjamin outlines what he learned about the craft of filmmaking from the directors he worked with as an actor. I’d be interested to see more of this.

Feminine Mystique: Chris Innis (30:41)

Award-winning filmmaker and editor Chris Innis – who produced and directed a 2014 documentary on the Perry’s previous film, The Swimmer (also being released soon on Indicator Blu-ray) – takes an in-depth look at Diary of a Mad Housewife. She discusses the influence of Betty Friedman’s 1963 feminist book The Feminine Mystique (hence the title of this piece), the rise of women’s movement and shaking off the 1950s ideal of the ‘perfect wife’, the role of Elaine’s restaurant in New York society of the day, lead actor Carrie Snodgress, Richard Benjamin’s performance as Jonathan, why the film is also important as a document of the city, and more. She also talks about source novel author Sue Kaufman and notes some of the key differences between the book and the film.

Theatrical Trailer (2:31)

Setting aside a misplaced, science fiction slanted electronic music score and caption creators who don’t know how many dots there are in an ellipsis, this is a surprisingly well crafted trailer, giving a flavour of the film and boasting a few effective editing flourishes. It also includes a bevy of positive quotes from contemporary reviews, which are captioned and read in the sober, almost downbeat voice that was in fashion with trailer-makers in the early 70s.

Larry Karaszewski Trailer Commentary (3:59)

Screenwriter Larry Karaszewski, filmed in the open air at what sounds like the height of the pandemic, reveals that he’s wanted to comment on this film since he joined the Trailers from Hell website, and was only recently able to do so when he tracked down a 35mm print and had it transferred. He outlines how the movie came to be, praises the work of Carrie Snodgress and Richard Benjamin, and salutes writer-director team Eleanor and Frank Perry, whom he believes don’t get the credit they deserve as pioneers of American independent cinema.

Radio Spots (1:33)

Three radio spots of increasing length in which an over-enthusiastic narrator barks out quotes from positive reviews, one of which describes Frank Langella’s performance as “Satanically sexy,” which echoes Justin Bozung’s comments about the similarity of the character of George to Count Dracula.

Image Gallery

42 screens featuring colour and monochrome publicity stills, lobby cards, two pages from the Universal publicity book, the cover of Sue Kaufman’s source novel from an edition released after the film adaptation, and international posters, including a brilliant Polish one whose content I won’t spoil here – definitely check it out, but only after you’ve seen the film.

Booklet

Paula Mejía, the culture editor of Texas Monthly, delivers an eloquent examination of the film in a fine lead essay. I particularly liked her observation – which should be obvious but somehow didn’t strike me as clearly as it did Mejía – that this was “a novel written by a woman, adapted to the screen by another woman, and filmed by a man, through the perspective of the leading female character.” Next is a useful essay on author Sue Kaufman and her novel Diary of a Housewife, one that handily reveals for those of us who have never read it that it was indeed written as a diary, hence the title – some elements that were changed for the film adaptation are also noted. Next are extracts from interviews with Eleanor and Frank Perry, both individually and – in an argumentative piece for the New York Times – together, plus a brief chat with Carrie Snodgress, who talks about the veracity of the events and dialogue within the film. Following this are short but telling extracts from Eleanor Perry’s novel Blue Pages and the screenplay for a film that was ultimately never made titled Somersault. A short piece on Carrie Snodgress and her marriage to Neil Young after he became captivated by her performance in the film is followed by extracts from three contemporary critical reviews. Full credits for the film are included.

We like to think that the days of women marrying into what is effectively domestic servitude is a thing of the past in modern western society, but much of what happens to Tina in this film was experienced by someone very close to me until she finally escaped her many years of abusive marriage. And while we’ve come a long way since the 1960s, you won’t have to look far to find example of continuing gender inequality and a rampant sexism. I’m not a sports fan, but even I was aware of the surge of good feeling there was in the country for the Lionesses’ European Cup football win. Yet just two days ago in the changing room of the health centre at which I go swimming, I overhead a group of five blokey males – who I can bet were screaming at the TV screen and punching the air repeatedly during the last World Cup – all dismissing this win as overblown and largely irrelevant because, you guessed it, we’re talking about women here, and in their view they only won because the other teams were even weaker than them. Imagine what it’s like being married to one of these dunderheads…

As I mentioned above, ideally Diary of a Mad Housewife should be watched with an eye on the socio-political changes facing Western society at the time, and while it can seem to hammer the point home at times, back in 1970 this was a point that needed a good pounding. This is another first-rate disc from Indicator, with a fine HD transfer and a substantial collection of high quality extras, including what may be the only surviving copy of the TV recut of the film. Warmly recommended.

|