| |

"When I wrote Devil I had a simple thought in mind. I wanted to tell a story about Los Angeles that highlighted black life and the black contribution to culture within a mirror-darkly that partially reflected the American experience within a shadowy landscape of national shame." |

| |

Devil in a Blue Dress author Walter Mosley interviews on Crimereads* |

Film noir is a genre – or perhaps that should be sub-genre – that in its purest form is generally tied to a specific time and place, that of 1940s and 50s (and at a pinch, early 60s) America. So great was its influence that it keeps returning under various guises, from the modern day neo-noirs to the tech-noir of Blade Runner and the cyberpunk sub-genre. Attempts to recreate the exact feel and period of the films that defined the genre too often come across (and are sometimes intended) as pastiche, and the whole concept of the hard-boiled detective of old has become a popular figure for parody. Any modern take on the genre that aims to play it straight, particularly one set in the 40s or 50s, thus has a job-and-a-half on its hands if the audience is going to take it as seriously as intended. Precious few have pulled it off, notable favourites being Roman Polanski’s Chinatown and Curtis Hanson’s L.A. Confidential. Another that did so with style was writer-director Carl Franklin’s 1995 Devil in a Blue Dress.

If you’ve never seen the film and have somehow assumed that it is just a standard noir crime tale with black actors cast in roles traditionally occupied by white characters as an exercise in tokenism, you can take those dumbass opinions right out the door with you. Even if that were the film’s only unique quality, it would be worthy of note for the culturally different take it would bring to the story, but although heavily influenced by the noir detective thrillers of old, Devil in a Blue Dress plays out from a black perspective because that’s how it was written. Faithfully adapted by Franklin from the 1990 novel of the same name by acclaimed author Walter Mosely, the film revolves around the character of Easy Rawlins (Denzel Washington), a World War 2 veteran who, as the film begins, is sitting in a bar scanning newspapers for new employment after losing his job at an aviation defence plant in Los Angeles during the summer of 1948. When a man named Dewitt Albright (Tom Sizemore) drops into the establishment to speak to its owner Joppy (Mel Winkler), Easy is called over to meet this out-of-place white visitor, who suggests he drop by his place if he is looking for work. When Easy follows up on the offer that evening, Albright reveals that he has been tasked by his friend, mayoral candidate Todd Carter (Terry Kinney), to locate his fiancée Daphne Monet (Jennifer Beals), who has been missing now for two weeks. Albright needs Easy because Daphne has a fondness for jazz clubs and what Albright crudely describes as “dark meat,” and was seen recently at an illegal club that a white man like Albright is unlikely to even gain entry to, let alone question the clients. He pays $100 up front and only requests that Easy ask around and let him know where the absent Daphne is.

The cash-struck Easy apprehensively accepts the job and visits the club to start asking questions about Daphne’s whereabouts, but as you might expect from any tale that wears the noir badge, things then quickly complicate. The reactions Easy’s questions provoke from his good friend Dupree (Jernard Burks) and his girlfriend Coretta (Lisa Nicole Carson) suggest they know more than they’re letting on. When Dupree gets so drunk that Easy has to carry him home, he is seduced by Coretta, who during the course of their night together reveals that Daphne is involved with a local gangster name Frank Green (Joseph Latimore). The following evening Easy meets again with Albright, but when he returns home the following morning he is accosted by two burly police detectives (John Roselius and Beau Starr), who haul him in for a brutal bout of questioning, during which they reveal that Coretta has been murdered and he’s under suspicion. It’s almost a running gag in the movie that every time Easy returns home he’s confronted with trouble of one sort or another, and after a while I began to tense up every time he pulled into his drive or answered a knock at the door. In my favourite of these he is pestered as he walks towards his house by a pesky but essentially harmless local gardener (Barry Shabaka Henley) with an obsession for cutting down trees. Easy repeatedly brushes him off but eventually turns in frustration just in time to hear the words, “There’s a man…!” and thus dodge a potentially lethal attack by Frank Green.

The film starts earning its noir credentials straight after the stylish title sequence concludes, as the camera drifts up from a busy street scene towards the upstairs bar in which Easy is scouring the job ads, where the scene is set delivered by his own reflective narration – “It was summer, 1948, and I needed money…” Easy himself ticks all the right boxes, being a solo figure who is drawn into a web of intrigue by a seemingly simple job, one that quickly blows up in his face and involves him in dark dealings and several deaths. There’s a dangerous bad guy, a handful of thugs and two detectives who do their talking with their fists. We even have a potential femme fatale in the shape of Daphne Monet, the devil in a blue dress of the title, though it seems likely from an early stage that she is more a victim than the lethal seductress of genre legend. Yet although very much a classic noir in its content and its characters, the film also plays some interesting games with genre traditions. For a start, Easy is not the hard-boiled detective of Hammett and Chandler, but an everyday guy who over the course of the film evolves into the resourceful detective he might later become.* It also eschews the traditional dark expressionist shadows and light pools of traditional noir in favour of what director Franklin has described as a more social realist feel, albeit one with a strong sense of the period. Visually, it’s utterly seductive from the off, thanks in no small part to veteran cinematographer Tak Fujimoto’s gorgeous lighting camerawork, Sharen Davis’s costumes, Gary Frutkoff’s production design and the golden hues of some judicious filtration and post-production colour timing. This is sonically underlined by an atmospheric score from master composer Elmer Bernstein and an evocative selection of period tunes.

What really differentiates Devil in a Blue Dress from the classic noirs of old, of course, is the fact that this is all told from an African-American perspective, which due to the 1940s setting has the potential to serve as a pertinent discourse on racism in America. Perhaps surprisingly, this is never hammered home and instead becomes part of the fabric of the film and into the narrative. It’s even responsible for kicking off the plot, with Easy losing his job at the aviation plant due to his skin colour, let go for unspecified reasons but ones we know that his white colleagues are not even reprimanded for. The more dangerous side of this prejudice arrives in the form of three male youths who threaten Easy for talking to their female friend, yet even this is used primarily to advance the narrative when Albright shows up and sadistically humiliates one them at gunpoint, revealing for the first time just how dangerous he is. A further indicator comes when Easy first meets up with Daphne in her hotel room and has to be sneaked in by a (black) bellboy because this portion of the building is reserved for whites only. Yet the film also kicks against expectations and tradition in the reason given for Easy’s urgent need for money, which proves to be not to settle gambling debts or boarding room bills, but to pay the mortgage on a house he has bought in a good neighbourhood in which black families have built a community that borders on being classified as middle-class.

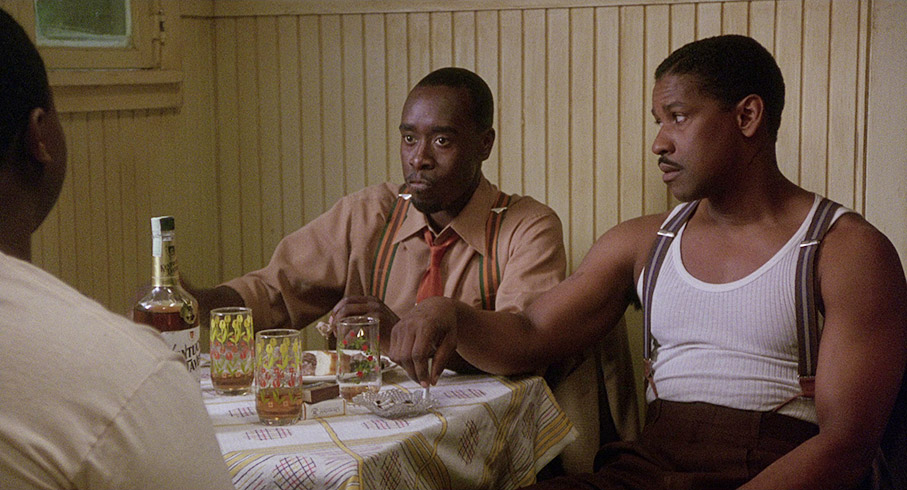

A terrific cast is on fine form here, with Denzel Washington – who by this point was a commanding screen presence – nicely kicking against expectations by playing Easy as a vulnerable everyday guy who takes the odd beating, is appropriately scared for his safety when the situation commands (his body language in the police interrogation tells its own story) and only seems ready to take affirmative action when he has a dangerous friend to back him up. Ah, the dangerous friend. It didn’t surprise me to learn that when the film was released there was a critical consensus that as Easy’s childhood pal Mouse, Don Cheadle comes close to stealing every scene he’s in. An unpredictable hard man with sociopathic tendencies whose default approach to conflict is to point a pistol at his opponent’s head, Mouse is the epitome of an oddly likeable monster, the sort of friend you’d probably steer clear of in real life but who in a noir crime thriller makes for the perfect sidekick. You want to threaten me? Well, let me introduce you to Mouse. Not so tough now, are you? The film also pulls a smart one by not bringing him into the story until after the halfway mark, and from the moment he walks into Easy’s house there is a very real shift in the balance of power. His decisive appearance during the climax is a perfectly-timed treat, and he also has my favourite line of dialogue, when a man Easy left him guarding ends up dead and he brushes Easy’s incredulity off with, “Look, if you ain't wantin’ him killed, why’d you leave him with me?” Tom Sizemore is textbook casting as Albright, having just the right degree of subtle shiftiness in his first encounters with Easy and making for a genuinely threatening figure later, and while Jennifer Beals is initially only required be enigmatically alluring as Daphne, she really delivers the goods as her character’s surface image crumbles and her fears for her own safety emerge.

Carl Franklin directs with a clear love for films that he draws inspiration from rather than trying to ape their style, telling his story with seductive a blend of formal framing, smart camera moves and neatly executed handheld work during moments of physical or emotional conflict. His pacing is also spot-on, keeping the story moving at an old-school pace but still allowing for moments of reflection and realisation on Easy’s part. The intermittent bursts of action are also handled with serious aplomb, with the fight between Easy and a knife-wielding Frank Green and an unglamorous climactic shoot-out being notable highlights. It all comes together deliciously, and the result is an immensely enjoyable, classily made and splendidly performed melding of traditional noir and neo-noir revisionism, and an object lesson in how to tell a damned good crime story on film.

A terrific 1.85:1 transfer with a lovely level of detail and handsomely balanced contrast (the opening street shot is an eye-popping example of both at their best), and attractive reproduction of the film’s toned-down, earthy colour scheme, which briefly gives way to vibrancy when capturing the blue dress of the title. The black levels are generally crisp and soften just often a tad in a handful of darker close-ups in order to preserve shadow detail. The image is free of damage and dust and a very fine film grain is visible.

There are two soundtrack options, Linear PCM 2.0 stereo and DTS-Master Audio 5.1 surround. Both are in excellent shape, being clear as a bell with a vibrant dynamic range and distinct separation on music and location effects. Inevitably, the 5.1 is a touch brighter and more inclusive, spreading the sound around them room and boasting some really punchy bass when required.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Audio Commentary with Carl Franklin

A most engaging commentary by director Carl Franklin, who avoids the trap of just describing what’s happening on screen (as some are wont to do) and instead focusses on his approach, his technique, some behind-the-scenes stories and the process of making the film. Areas covered include the title sequence, the use of street scenes to open up the film (a technique he learned from Marcel Carné’s Les enfants du paradis), the role of alcohol as a Faustian symbol, the locations, the actors and bit-part players, the period photographs he drew on to research the film’s look, the colour timing, the alterations made to the source novel, the principal themes, and much more. He praises the work of the performers and those working behind the camera, highlighting the preparation work done for their roles by Denzel Washington and Jennifer Beales and the handheld camerawork of operator Scott Sakamoto. He also reveals why some material was shot and then removed from the final cut and aspects in which the film turns standard noir tropes on their head. I really enjoyed this.

Carl Franklin: Dancing with the Devil (22:14)

An onstage introduction to a screening of Devil in a Blue Dress and a brief post-screening interview in which director Carl Franklin chats to film historian Eddie Muller at Noir City Chicago, Music Box Theatre on 17 August 2018. Although there is some brief crossover with the commentary, much of what is discussed here adds to rather than repeats Franklin’s comments there. He talks about how he first got the directing bug, how he came to this project and the involvement of executive producer Jonathan Demme, adapting the novel into a screenplay, creating the film’s toned-down colour scheme, his love of noir cinema, and more.

Don Cheadle Screen Test (15:01)

Carl Franklin introduces video footage of Don Cheadle’s screen test for the role of Mouse, in which he plays three scenes – one of which is repeated twice – in which an unseen Franklin and Denzel Washington feed him dialogue to respond to. It ends on my favourite line (see above), the delivery of which causes everyone to break down laughing.

Theatrical Trailer (2:27)

A really well-edited and seductive trailer whose potential spoiler moments are cut together too swiftly to really be harmful. A very nice sell.

Image Gallery

21 screens of slightly sub-par promotional stills (at least compared to the scalpel-sharp ones we often see in these galleries) plus a single poster.

Booklet

Opening, as ever, with the main credits for the film, this 40-page booklet then moves onto an essay by Keith Harris, who is Associate Professor in the Department of English and

the Department of Media and Cultural Studies at UC Riverside. Its title is up-front about something I considered including in my review but ended up omitting, that the French term ‘Film Noir’ translates as ‘Black Film’ and thus has special meaning here. It’s a really good read that absolutely nails many of the film’s qualities. Up next is an interview with writer-director Carl Franklin, in which he talks about what drew him to the book, the changes he made to it for the film adaptation, the choice of music, and more. Following this is the opening seven paragraphs of Walter Mosley’s novel, in which Easy observes Dewitt Albright’s arrival in Joppy’s bar. Finally we have extracts from three pleasingly positive contemporary reviews, with Manohla Dargis neatly observing in Sight & Sound that Franklin “put the noir back into film noir and crossed over into the world.”

I’ve been a fan of Franklin’s film since I first saw it back in the 90s, but coming back to it after a gap of several years I was struck not just by how strong all of its constituent parts are but just how effortlessly they all gel together. It’s a terrific entertainment and stylish one, and it looks and sounds superb on this Indicator Blu-ray, which also boasts some first-class special features. Enthusiastically recommended.

|