|

It would be fair to say that for most western viewers, the name Nakata Hideo (as usual, I'm going with the Japanese convention of surname first on all Japanese names here) was an unknown quantity before the release of his breakthrough second feature Ringu, which remains one of the most influential (not to mention the scariest) films of late twentieth century horror cinema. For many of that film's fans, his follow-up Ringu 2 was a bit of a disappointment, and his mind-bendingly complex Kaosu [Chaos] took its sweet time coming to the UK in any form. So the news that a new Nakata film was on the way, also adapted from a story by Ringu author Suzuki Kôji, generated quite a bit of pre-release excitement back in the summer of 2003. But in spite of a number of similarities to Ringu in both its underlying themes and cinematic technique, Dark Water (Honogurai mizu no soko kara – literally, ‘From the Bottom of the Dark Water') proved to be a somewhat different beast.

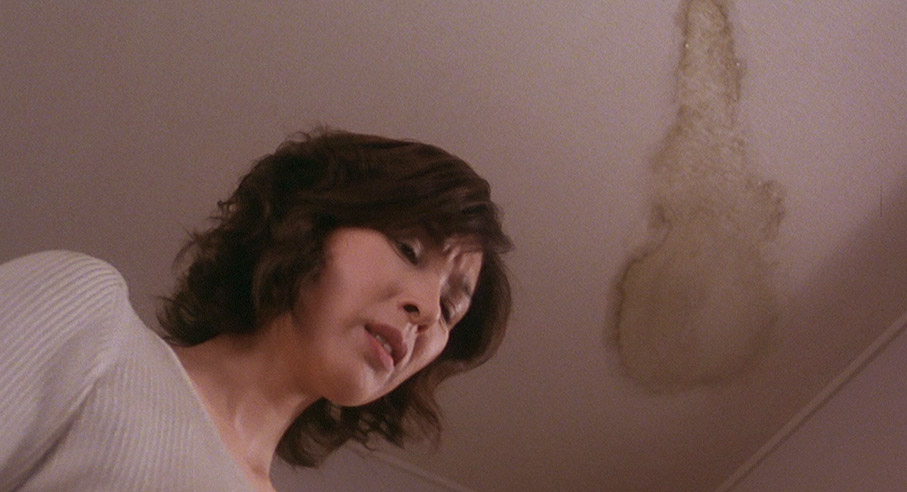

Having recently separated from her husband, Yoshimi is now fighting a legal battle with him over the custody of their 5-year-old daughter Ikuko. With money now tight, she and Ikuko move into an apartment in a run-down tenement block, and they've not been there long before odd things start happening: a water stain on the ceiling begins to spread and leak into her apartment; a discarded red school bag repeatedly returns to the building, despite Yoshimi's repeated attempts to dispose of it; and both she and Ikuko begin catching glimpses of an unidentified young girl in a yellow rain coat. Yoshimi soon begins to suspect a link between these seemingly disconnected elements and the still unexplained disappearance of Mitsuko Kawai – a girl of Ikuko's age who attended the same kindergarten – two years before. Her suspicion is strengthened when she learns that Kawai lived in the now abandoned apartment directly above theirs, from where the water staining their ceiling appears to be leaking.

There are a number of immediately evident similarities between Ringu and Dark Water, aside from the shared author of their source stories: both feature a female lead character who is separated from her husband and is the guardian of their small child; both have nerve-janglingly effective (and not dissimilar) scores from Kawai Kenji; both are supernatural tales that play out in modern urban settings; and both are built around the uncovering of a mystery that has the suffering of a single, lost individual at its core. Indeed, these similarities prompted some to be a little dismissive of Dark Water on its initial UK release, largely, it would seem, because it failed to simply re-run Ringu with a new set of shocks and twists. Certainly there was some disappointment expressed by the younger Ringu fans at our film society screening, but older viewers seemed to take a different view – they got what Nakata was up to, something second and third viewings make increasingly clear. For while Ringu was a supernatural horror story with a strong emotional core, Dark Water employs the trappings of a ghost story to tell a deeply moving and thoughtful tale of the pain of separation, the effect it can have on a child caught in the middle, the generationally repetitious nature of human behaviour, and the extraordinary lengths a devoted mother will go to in order protect her child from harm.

The horror genre's ability (and at its best, tendency) to seamlessly incorporate social commentary into a genre narrative and explore it through subtext and allegory is key to its longevity and cult popularity, and on occasion allows filmmakers to address issues in a more layered and interesting way than films that take a more direct approach to the subject in question. The issue of marital separation and child custody is a perfect example – Robert Benton's Kramer vs. Kramer and David Cronenberg's The Brood were released the same year (1979) and both dealt with this head on, but while the former won all the awards, it was Cronenberg's altogether more personal film, with its disturbingly metaphoric look at the emotional and physical damage that can result from such a break-up, that for many was always the stronger and more honest work.

Nakata's approach to this is initially up-front – the first scene featuring the adult Yoshimi has her and her husband in separate custody discussions with grey-suited bureaucrats as rain pours outside, an expressionist reflection of Yoshimi's melancholia and a pointer to the significance of water in scenes to come. This comes to a head later when Yoshimi arrives late to pick up Ikuko from school (a fate she had also repeatedly suffered as a child) and ends up in a physical tug-of-war with her husband over their child with both of them refusing to surrender her to the other, while Ikuko herself seems uncertain with whom she actually wants to be. Increasingly, however, this element takes a more subtextual role in the story, climaxing in an extraordinary womb/birth metaphor involving a water-filled elevator that is clearly designed to be read (and in narrative terms understood) primarily in symbolic terms. This gives the drama an emotional depth and purpose beyond that of simply scaring the audience – on my second viewing I found this sequence genuinely heart-breaking.

All of which may make the film sound like a scare-free social drama masquerading as horror, but having demonstrated his ability to seriously unsettle an audience and deliver a good jump-scare in Ringu, Nakata is not about to rest on his previous laurels here. There is an almost other-worldly creepiness established from the start by the constant rainfall, which bonds atmosphere to plot in a manner that recalls Peter Weir's The Last Wave (1977), Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now (1973 – the influence extended to the raincoat-wearing young girl and the use of symbolism) and even the opening scenes of Dario Argento's Suspiria (1977). That the first ceiling stain is ring-shaped may feel a small in-joke on Nakata's part, but as it spreads, tentacle-like, across the room it becomes a strangely menacing presence – when Yoshimi wakes to find the bed she is resting on soaked with water from this stain, which appears to have grown to position itself above her, the effect is genuinely unnerving. And there's a genuine, in-story logic to this, one echoed in other sequences and reaching a discomforting peak when Ikuko is playing hide-and-seek at school, and is slowly approached by an unidentifiable girl who appears to be leaking water, streams of which then snake across the floor towards Ikuko like predatory tentacles.

If some of Nakata's cinematic jolts seem to have less meat than their Ringu equivalent – the reappearance of the red bag is never as alarming as that distorted polaroid in the earlier film, but both are given a similar visual and aural bang – their cumulative effect is nonetheless every bit as unsettling. And late in the story, when Yoshimi spots a strangely smiling Ikuko attempting to look inside the bag in question, it's easy to share her fear at what might happen if she actually gets it open. As with Ringu, the film slowly gets under your skin, then in the final ten minutes of the main narrative (more on this in a minute) it really lets rip with a climax that delivers completely on thunderous atmospherics, sudden scares and boldly realised metaphoric horror. And despite the fact that most viewers will have worked out what lies behind Yoshimi and Ikuko's troubles long before the film itself chooses to reveal it, Nakata still manages to pull off a jarringly effective last minute twist, one that makes perfect sense in context of the film's subtextual concerns.

While the central mystery is not much of a mystery at all and some of the dramatic elements play out as expected, others do not. The introduction halfway though of Kishida, the good-looking and kind-hearted lawyer who takes up Yoshimi's case and smartly sorts out her landlord, initially seems designed to set up a Hollywood-style hero-saves-princess conclusion, but Kishida's role in the narrative proves to be a purely functional one. And while strong, self-sacrificing female lead characters go all the way back to the silent cinema of Murnau's Nosferatu (1922), they are still few and far between, and it's rare indeed to find one prepared to make the sort of sacrifice that Yoshimi is willing to make for the protection of her daughter here.

Performance-wise it's almost a one-woman show, with Kuroki Hitomi (who, perhaps co-incidentally, was in the Ringu TV spin-off Ringu: Saishû-shô 1999) required to run the full emotional range, cheerfully playing with Ikuko (in a scene that can't help recall a similar bonding sequence in The Exorcist and has become of a bit of a pre-trauma horror movie staple), angrily attempting to assault her husband for his underhand attempts to discredit her, and looking on with wide-eyed terror as an overflowing bath threatens to give birth to something unspeakable. But as the young Ikuko, Rio Kanno manages that rare trick amongst child actors of being sweetly engaging but never insufferably cutesy, and in the final stages displays a distress that is so gut-wrenchingly real that it brings tears to my eyes on every viewing and is key to the emotional punch of the climactic scene.

Which brings me to the ending. There has been a fair amount of criticism of the film's final ten minutes, a 'ten years later' coda that many felt was unnecessary and even tagged on. From a horror movie perspective this may well be true, but I would argue that from the social drama standpoint it is both appropriate and rather effective (I won't go into details, lest it spoil the film for those who haven't seen it), and lends considerable weight to one of the film's underlying themes. It is only a final, single line of the voice-over delivered by the now teenage Ikuko that for me feels clunky and completely unwarranted, spelling out for the slower audience members what the previous ten minutes had suggested with considerably more subtlety.

Dark Water is both an impressively low-key horror movie – not a drop of blood is split here – and an emotionally affecting social drama, elements that successfully compliment and interact with the other. It remains a supremely creepy cross-genre work whose characters we actually feel for, something that really hits home on subsequent viewings, when the small clues dropped in the early stages can be seen to have more specific purpose. That the inevitable American remake was directed by the talented Walter Salles and boasts a cast that includes such acting heavyweights as Jennifer Connelly, John C. Reilly, Tim Roth and Pete Postlethwaite cuts little ice with this particular purist – Nakata nailed it on the first attempt, and despite the valiant efforts of Salles et al, it's this compelling original I'll go with every time.

The 1.85:1 1080/24p transfer on the Blu-ray in this dual format set is certainly an improvement on previous DVD editions, particularly evident in the higher level of picture detail and the absence of the compression artefacts in the areas of similar shade or colour. In other respects, it faces similar challenges to its predecessors and does rather well by them, despite some variance in the quality of the results. The use of stripped-down colour and the storm cloud gloom can make the image feel like it lacks punch at times, and while this was clearly intentional, the black levels do sometimes soften, while elsewhere the contrast is strengthened to the point where the blacks are solid but some white highlights burn out. At its best this is a very good transfer and the best I've yet seen the film look on digital, and the detail is always clear and there are no traces of dirt or damage.

On the other hand, the DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track is downright superb, having a gorgeous dynamic range, clear rendition of dialogue and a wonderfully inclusive use of the whole 5.1 sound stage. This is especially effective in heavy rainfall, which fills the room in a manner that had me pulling up my collar and reaching for a hat. The bass notes of Kawai Kenji's score also send a deep rumble right through your chest. Excellent.

The English subtitles are clear and optional.

The first three interviews here have been newly recorded for this Arrow release and are conducted in Japanese with English subtitles. All three feature major spoilers for newcomers, so definitely save these until after the film.

Nakata Hideo: Ghosts Rings and Water (26:03)

Director Nakata provides a brief summary of how he entered the film industry and came to direct his first feature, Don't Look Up, then goes into considerably more detail about his approach on his breakthrough feature Ringu, outlining the key changes he and scriptwriter Takahashi Hiroshi made to the source novel (all of which got a thumbs-up from its author Suzuki Kôji). There's a rather nice story about him making cuts to Takahjashi's screenplay for Ringu 2, only to receive an unexpected fax at 4am in Takahashi's handwriting saying, “You're making changes to the script, aren't you.” That, he assures us, was scary. He also covers the production of Dark Water, including a falling out he had with one of the writers, and he surprised me by revealing that two sequences in which child actors appeared to be in physical danger were both done for real.

Suzuki Koji: Family Terrors (20:20)

The upbeat Sukuki, author of the stories on which both Ringu and Dark Water were based, reveals his inspirations for Ringu and reveals that he never regarded it as a horror novel but that it quickly acquired that label, which he admits actually helped him in the long run. He apparently has a contractual restriction that no blood or ghosts can be shown in any of the film adaptations of his work, which he believes forces the filmmakers to get more creative (and sorry, but technically there are ghosts in both Ringu and Dark Water, though they are inventively handled). He also assures us that the two factors needed for a truly scary story are moisture and a confined space. Let that one play around in your head for a while. There's plenty more interesting material here, and in a nice trick on the part of those who edited this, there's a flash frame of a large white ring as the picture fades at the end.

Hayashi Junichiro: Visualizing Horror (19:16)

Cinematographer Hayashi outlines how and why he went from being an assistant director to becoming a cameraman, and recalls first meeting Nakata Hideo and later working with him on Ringu and Dark Water. He clearly respects Nakata as a visual ideas man and discusses how they worked together these seminal horror works (Nakata is, we are informed, very specific about the degree of blurring in elements that are pushed out of focus in the background). He also goes into some detail about how camera crews work and are structured in Japan, which I at least found interesting. Intriguingly, he was always found horror movies too scary as a child, and when given some key works to watch for reference, he was unable to stay with any of them until the end. If the bar in which he is interviewed looks familiar to Arrow regulars, it's because it's the same one in which Yutaha Komina was filmed in for their Female Prisoner Scorpion box set, specifically Shinjuku Golden Gai's Snack Honey, which apparently burned down earlier this year but like Scorpion, we are informed on the earlier disc, it will return.

Making-of featurette (15:50)

A 4:3 framed making-of featurette from 2002 made up of behind-the scene footage from four locations and one studio shoot. One to avoid if you don't want your illusions shattered, and like the interviews above, this contains some fairly hefty spoilers.

Kuroki Hitomi Interview (7:59)

An archive interview with lead actress Kuroki in which she talks about what drew her to the project, her approach to the role, being directed by Nakata, and her prep for convincingly playing a mother to child actress Kanno Rio.

Mizukawa Asami Interview (4:38)

Another 4:3, SD archive featurette that includes footage of actress Mizukawa Asami's audition and a brief interview with her on set, where she talks about the script, the director, Suzuki's horror stories and her approach to the role.

Suga Shikao interview (2:54)

The style-conscious composer of the jarringly inappropriate song that runs over the film's end credits (you may well love it – I did not) talks briefly about its composition and themes.

Trailer (1:13)

A hurriedly paced trailer with a soundtrack that builds steadily in intensity, but opens with an extract from that end credits song.

Teaser (0:37)

A shorter but more intriguingly creepy sell.

TV Spots (0:50)

Three short TV spots. The second two are effective enough, but the first is onto a no-hoper from the start trying to sell this as scary horror with Suga's end credits pop song on the soundtrack.

Also included in the first pressing only is an illustrated collector’s booklet containing new writing by David Kalat, author of J-Horror: The Definitive Guide to The Ring, The Grudge and Beyond, and an examination of the American remake by writer and editor Michael Gingold, but this was not supplied for review.

A richly textured and thoughtful blend of family crisis drama and supernatural horror that is just loaded with suggestion and carefully crafted and meaningful subtext – re-watch the film and nothing in the first half is as random as it feels the first time around. Deeply unsettling and ultimately very moving, it's one of Nakata's most impressively realised works to date and one of the shining stars of the J-Horror cycle. The transfer on the Blu-ray of this dual format set is likely as good as the material allows (we don't get to see the Arrow booklets for review any more, so I can't confirm who actually did the restoration here), but Arrow have gone the extra mile with the new interviews and this is still far and away the version to get.

This film review has been updated friom our review of the earlier DVD release of the film.

|