|

Japanese ghost stories, particularly those made in the early second half of the 20th century, differ markedly from those made by western nations, in part because eastern and western notions of what constitutes a ghost tend to differ. When Nakata Hideo’s 1998 Ringu first made a splash in international markets, much was made – with good reason – of the creepiness of the spectral Sadako, with her pure white attire and her face hidden beneath a head of long black hair. Yet as my Japanese partner noted at the time of its release, that look is not unique to Nakata’s film, but an archetypal Japanese representation of a spiritual being, the vast majority of whom in Japanese film and literature tended to be female.

My introduction to Japanese horror cinema came from two directions, as I was introduced to the chills of 90s J-horror by Ringu and to the wonders of earlier Japanese genre cinema by Shindō Kaneto’s 1964 masterpiece Onibaba. Thus, as I worked my way through the post-Ringu J-horror catalogue, I was simultaneously being introduced to a whole range of classic genre works by my knowledgeable partner, a committed horror fan who grew up watching these titles and reading the books on which they were often based. Yet despite having watched every Japanese horror film that came my way over the years, there remain many highly regarded works that I have yet to and remain eager to see, hence my excitement when Radiance announced Daiei Gothic, a box set featuring restorations of three of these very films. All three were based on stories that were already famous in their homeland and that my partner instantly recognised when I read out the titles, and while I expected them to be good, I genuinely wasn’t prepared for just how good they proved to be. As the box set title suggests, all were produced by the Daiei Studios, and the special features in this set do a solid job of explaining why the production values on Daiei films were so much higher than their equivalent at a rival studio like Toei. That’s certainly reflected in the striking visuals and thoughtful use of sound in all three films, but also in the sheer skill with which these tales are told, and the unnerving, cut-it-with-a-knife atmosphere that they each slowly build.

But enough with the introduction, let’s get on to the films themselves. There are some spoilers ahead, but I’ve indicated where it might be prudent for newcomers to skip past the offending lines or paragraphs.

| THE GHOST OF YOTSUYA (1959) |

|

OK, I feel the need to preface this one, and you’ll need to go with me on this. Given that this review and the subtitles on this disc are presented in a sans-serif font, there is something I need to address before I even start talking about the first film in this set, the 1959 The Ghost of Yotsuya [Yotsuya Kaidan]. The leading male character’s name is Tamiya Iemon, and for clarification that means his family name is Tamiya, followed what we in the west would call a given name or forename (which in Japan is delivered after the family name), which in this case is Iemon. The problem for a western audience, particularly when this is used in isolation in a sentence, is that it reads like the name of a particularly sour fruit whose juice we like to squeeze onto fish. This is particularly true when it appears in lines of dialogue like, “Let’s hear a little more about this Iemon.” This is all down to the simplified nature of sans-serif fonts, where a capital “i” looks exactly the same as a lower-case “L”, a confusion not present with traditional serif fonts. Thus, be aware that Tamiya’s given name is pronounced “EE-EH-MON” and not “LEH-MON” Keep this in mind when you see his name written both here and on the subtitle text, as you’ll be seeing it quite a lot.

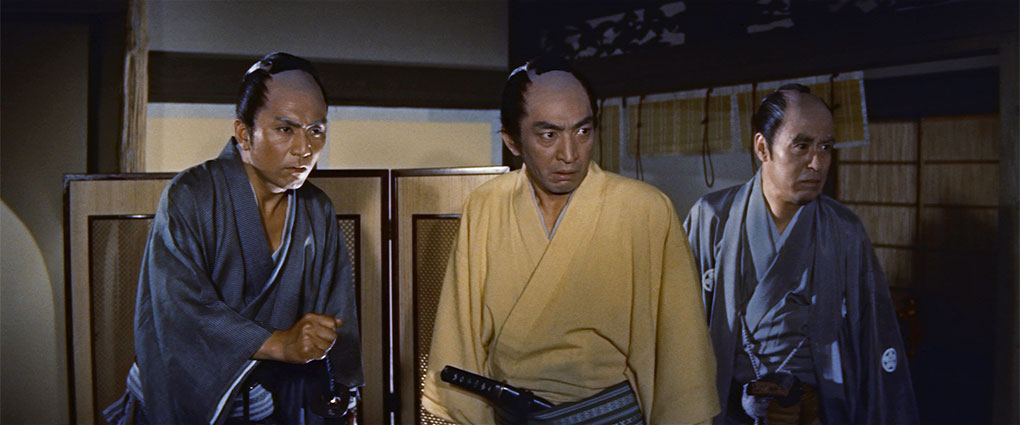

And so, to the film. The above-mentioned Tamiya Iemon (Hasegawa Kazuo) is an Edo-period samurai who lives in poverty with his devoted wife Oiwa (Nakada Yasuko) and is reduced to making a few ryō by crafting and selling umbrellas. That he may be a bit of a layabout is suggested early on when he quickly becomes bored with his work and decides to go fishing instead, which disappoints Oiwa, who is still recovering from a recent miscarriage and clearly wants to spend more time with her husband. This in turn upsets their servant Kohei (Tsurumi Jōji), who is completely devoted to his mistress, feelings that he knows he must keep to himself.

Shortly after Iemon departs, Oiwa is visited by her more gregarious sister, Osode (Kondō Mieko), who shows her material that her clothier boyfriend Yomoshichi (Hayashi Naritoshi) would like to make into a new kimono for his future sister-in-law. Their conversation is interrupted by the arrival of Gombei Naosuke (Takamatsu Hideo), a reprehensible opportunist who is looking for Iemon, whom he then locates at his favourite fishing spot by the canal. His two partners in crime, Akiyama (Sugiyama Shōsaku) and Sekiguchi (Suga Fujio) have run into trouble and are desperately in need of Iemon’s help. Reluctantly, Iemon accompanies Naosuke, and brusquely deals with the armed and angry men who are attacking Akiyama and Sekiguchi, and does so without once drawing his sword.

Unbeknown to Iemon, Oiwa has asked her influential uncle (whose name is never mentioned, so I’m not sure of the name of the actor who plays him) to help secure her unemployed husband a government position. When Iemon returns home, the uncle is waiting, and after berating his nephew for his failure to find work, tells him of an available position and advises that he should visit Lord Ito Kihei (Arashi San'emon) to secure it. Iemon is seemingly unmoved, and claims that such jobs can only be obtained with a substantial bribe, prompting the uncle to condemn him for his cynicism and ensure him that a bucket of sake is the standard gift when applying for such posts. What at first comes across as the idle Iemon inventing a reason for not even applying for the post proves instead to be an acute awareness of political reality when his gift of sake is mercilessly mocked by Ito while Iemon is still within earshot. Angry and humiliated, Iemon heads straight for the nearest bar, and when two frightened women, Oume (Uraji Yōko) and her maid, burst inside and beg for his help to fend off a band of drunken and entitled samurai, Iemon takes his bad mood out on the men, once again defeating them all without drawing his sword from its scabbard. The women are hugely grateful, but Iemon tells them that he didn’t fight the men for their benefit and that there’s no need to thank him, then pays his bill and departs. Oume, however, is bewitched by this skilled stranger and desperately wants to know his name and meet him again, a spoken desire overheard by the unscrupulous Naosuke, who leaps at the opportunity to make a little money at his supposed friend’s potential expense.

I should note at this point that we’re only 15 minutes into an 83 minute film, and in terms of twisty and intertwining plot strands, screenwriter Yahiro Fuji and director Misumi Kenji are just getting started. Still to come is Naosuke’s leery lust for Osode and his forceful attempts to take advantage of her, the night-time work as a courtesan undertaken by Osode that she keeps secret from her sister, the revelation that Oume is Lord Ito’s daughter and thus able to pressure him into reluctantly giving the vacant position to Iemon, and the ways in which her maid works with Naosuke, Akiyama and Sekiguchi to bring Iemon and Oume together, and ultimately put Oiwa out of the picture.

Before I proceed, I should confirm to anyone new to the site that I am a great admirer of the work of director Kurosawa Kiyoshi and regard his 1997 Cure [Kyua] as one of finest and most psychologically disturbing films of late 20th century cinema. But when, in the special features on this very disc, he suggests that the events that ultimately lead to Oiwa’s unjust fate were triggered from the start by her jealousy of her husband, I found myself wondering if we’d watched the same film. Oiwa’s only crime, if it can be so described, is that she dearly loves a man who too often takes her for granted, and who seems largely indifferent to her desires and needs, a situation that deeply frustrates their servant Kohei, whose genuine love for Oiwa decorum dictates must remain unrequited. Yet first impressions of Iemon also do not paint the whole picture, as despite his seeming self-centredness, when it comes to his relationship with Oiwa he takes the bonds of marriage seriously, seemingly blind to Oume’s initial expressions of gratitude and dismissing her later attempt to seduce him by reminding her that he is a married man. His more callous side still surfaces when he fails to notice the new kimono that Yomoshichi has made for his wife (“I thought it was one of your old ones from when you were young”), yet when his involvement with one of Naosuke’s schemes lands him some money, he buys Oiwa a beautiful comb and gives the remaining money to her. When Oiwa does become jealous, she does so with good reason, as by then Iemon is spending more time with Oume than he is with his wife and starting to fall under her determinedly cast spell.

The decision to make him more sympathetic than he is in the story on which this film is based was apparently influenced in part by the casting of then popular actor Hasegawa Kazuo in the role, but it also helps differentiate this take from other film adaptations of the same story, which include Tōkaidō Yotsuya kaidan, released the same year and directed by Nakagawa Nobuo. Here, Iemon is not the villain, but an inattentive dupe who is manipulated by unscrupulous others to work against his own and especially his wife’s best interests. It seems only fitting that after winning two fights against multiple opponents without drawing his sword, when he finally does so it’s against those that have deceived him and so terribly wronged Oiwa.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about The Ghost of Yotsuya, particularly given the unambiguous nature of its English language title, is that it does not play as a ghost story at all for the first two-thirds of its run time, instead unfolding as a compellingly handled relationship drama. Indeed, you could almost be forgiven for wondering during the first two-thirds if the title is metaphoric, only for a key sequence involving what Oiwa has been mistakenly assured is medicine to then move the film rapidly into the realms of full-blown horror. What follows is littered with genuinely chilling and forward-looking scenes, with a spectral hand that emerges from a washing bowl prefiguring the final jolt in Carrie (1976), and a riverside encounter with a vast net of human hair that has echoes in a whole range of later J-horror works. It builds to a gorgeously dark and ferocious climax in which terrible wrongs are punished by a combination of supernatural intervention and physical action, and whose finale (big spoiler ahead, so skip to the next film to avoid), sees Iemon and Oiwa finally reunited in death, with the suggestion that, despite Iemon’s earlier indifference and unknowingly destructive selfishness, he is forgiven and embraced in the afterlife by the still loving Oiwa.

In the midst of a snowy mountain landscape, master sculptor Shigetomo (Hananuno Tatsuo) and his apprentice Yosaku (Ishihama Akira) stumble across the mighty tree for which they have so long been searching, and from which Shigetomo has been commissioned by the high priest to carve a statue of the goddess Kannon to fill an empty plinth at the provincial temple. When the weather deteriorates, the two men take shelter in an empty hut for the night, but as they are sleeping a legendary white-faced phantom known as the Yukionna – the Snow Woman of the title – enters and freezes the still unconscious Shigetomo to death. Her actions are silently observed by the petrified Yosaku, who is lying nearby and doubtless well aware of the legend that anyone who lays eyes on the Snow Woman will perish. The Snow Woman then realises she is being watched and approaches Yosaku, who remains rooted to the floor in fear. After briefly observing him, she tells him that because of his youth and beauty she has decided to spare his life, but only on the condition that never tells anyone what he has just seen, no matter how dear they are to him, “Not your parents, nor your children, nor even your wife.” If he breaks his promise, she assures him, she will return and kill him. Unsurprisingly, it’s a condition that the terrified Yosaku readily agrees to.

On his return to town, Yosaku tells Shigetomo’s widow Soyo (Murase Sachiko) that her husband froze to death after they forgot to put wood on the fire during the night, a story she accepts as the truth despite a nagging feeling that Yosaku is not telling the whole story. Having never had children or her own, and with Yosaku an unmarried orphan, Soyo treats him as the son she never had, and he in turn takes care of his surrogate mother. Both are excited when the tree that Shigetomo located is finally cut down and brought into the town, but Yosaku is then surprised when the High Priest commissions him to carve the statue in his late master’s place, a great honour that he humbly accepts but fears that he may not be up to. He nonetheless dedicates his time to improving his sculpting skills while the wood undergoes the slow but necessary process of drying out. Then one day a beautiful young woman named Yuki (Fujimura Shiho) takes shelter from a rainstorm under the awning of Soyo’s house and is invited by Soyo to come inside to dry off and stay the night, and Yosaku quickly finds himself falling for her, and she for him.

If you’ve never seen or read about the 1968 The Snow Woman [Kaidan yukijorō] and any of the above sounds remotely familiar, it’s because the ancient folklore-inspired short story by celebrated writer Lafcardio Hearn on which Yahiro Fuji’s screenplay is based was also realised on film as the second episode in Koboyashi Masaki’s more widely known and seen 1964 horror anthology, Kwaidan. Indeed, you could argue that the short format morality tale of Hearn’s original is better suited to the briefer running time devoted to it there than it would be to a feature-length film. Yet while the visually and aurally striking adaption in Kwaidan remains closer to the text of Hearn’s tale, Yahiro and director Tanaka Tokuzō creatively expand on it in interesting ways. By transforming the story’s young woodcutter into a talented apprentice of a master sculptor, Yahiro and Tanaka lay the ground for the introduction of a human antagonist in the shape of Lord Jito, an almost archetypal villain whose brash arrogance and sense of entitlement are nonetheless plausible traits of a man in his position of power at this point in Japanese history (and frankly are still on open display in Trumpian America today). They lay the ground for future conflict by having Jito become entranced by Yuki’s beauty, then by having him introduce respected master sculptor Gyokei (Suzuki Mizuho) to the High Priest, whom he then convinced to allow Gyokei to pit his skills against those of the less experienced Yosaku. He even has Yosaku arrested for cutting down the tree from which his sculpture is being carved, despite the fact that he had obtained official permission for its felling. It’s a crime that the arresting officers claim is punishable by life imprisonment, at least unless Yuki throws herself at Jito’s mercy and “earns his affection.” When she expresses her open disgust at this suggestion, she is told that Yosaku must instead to pay three ryō for the tree, a sum that a man of his humble means could never afford. A furious Yuki then tells them that she will pay the fee, which surprises the lead officer, who gives her just five days to raise the money.

Before I proceed, I feel obligated to issue a tepid spoiler warning for what lies ahead, tepid because the central moral of this tale is a simple one whose outcome most viewers should be able to predict at an early stage. Couple this with the fame of Hearn’s story in what became his adopted home country, and it comes as no surprise when the tale’s central twist is slyly confirmed just 30 minutes into this 80-minute film. Thus, if you are completely new to this story in any of its forms and would like to chance not being able to predict how it unfolds, then skip to the final paragraph of the review of this particular film.

Right, as all who know the story or have seen its earlier film incarnation them will be aware, the promise made by Yosaku to the Snow Woman early in the film is destined to be broken by the film’s end. Even if you’ve never encountered this tale before, the passing of time has ensured that such pledges are rarely honoured, and the expectation that the individual in question will betray their promise takes the sting out of any intended surprise when they do. Impressively, the filmmakers here exploit that foregone conclusion and the contemporary domestic audience’s familiarity with the source story to torture us with the forlorn hope that, just this one time, Yosaku might keep his idiotic trap shut. The fact that Yuki is the Snow Woman in earthly form will likely also not have come as a huge surprise to a Japanese audience, given that ‘Yuki’ is the Japanese word for ‘snow’ and ‘Yukionna’ literally translates as ‘Snow Woman’. Countering that is the fact that Yuki was a common female name during the period in which the story is set, and despite both characters being played by actress Fujimura Shiho, the striking, white faced make-up and golden eyes of the Snow Woman, coupled with Fujimura’s acting, ensure that she and Yuki really do look like different people. The late story revelation of her true identity may have come as a surprise in Hearn’s story, but Yahiro and Tokuzō here are wise to their audience, and openly confirm Yuki’s true identity early on in her marriage to Yosaku, when Yuki is recognised for who she really is by an ageing female shaman, who reacts to her presence at a public prayer meeting by launching purifying embers in her direction. This prompts Yuki to briefly flash a vengeful glance at the shaman, her eyes transformed momentarily to the golden ones of the Snow Woman, before rapidly fleeing the scene.

We’re just past the halfway mark when Yuki’s true identity is confirmed beyond all doubt, when she responds to Lord Jito’s threat to imprison her husband by visiting the District Governor’s house, where her claim to be the daughter of a doctor sees her granted admittance on her promise to help the Governor’s seriously ill young son. This she does out of sight of the family using her power as the Snow Woman to gradually reduce his fever by lowering his body temperature, a task that leaves her physically exhausted but nets her the family’s gratitude and a three ryō reward that she uses to pay off Lord Jito’s men. This marks a real turning point for the film, shifting our sympathies from Yosaku to Yuki, who for me became the undisputed central character from this moment on. It also transforms the moral tale of the source material into a gripping tale of a strong woman who, after countless years in the wilderness in spectral form, finally find happiness and true love as a mortal woman, and who will do anything to protect her husband and the young son that she bears him. Despite the fact that she doesn’t age, her desire is clearly to remain in mortal form and with her family for as long as they may live, and she only calls on her powers as the Snow Woman when they, or in one crucial (and ultimately satisfying) case, she herself is threatened. This culminates an emotionally devastating climactic scene, where Yosaku’s decision to reveal what happened that fateful night after honouring his pledge for so long plays as a terrible betrayal, and leads to an ending that while definitely sad in the Kwaidan episode, is genuinely heartbreaking here.

On my first viewing of The Snow Woman I became a little too caught up in spotting the changes made to the source story and the similarities and differences to the Kwaidan adaptation, both of which I have become very familiar with over the years. On a second viewing I was able to put all this aside and quickly found myself immersed in the story and the hypnotically beautiful manner of its telling. Yes, the Kwaidan version is more visually striking, but not by a huge margin, thanks in no small part to cinematographer Makiura Chikashi’s gorgeous scope cinematography and Naitō Akira’s richly evocative art direction. Also key to the film’s success are a solid performance from Ishihama Akira as Yosaku and a knockout one from Fujimura Shiho as both Yuki and Yukionna. I also have to give a shout out to child actor Saitō Shinya as their young son Tarō, whose painfully desperate pleas to his mother in the final scene never fail to bring me to the brink of tears. It’s an extraordinary film any way you like to cut it, wonderfully eerie and unsettling as a tale of the supernatural, but really hitting home as an involving and ultimately heartrending story of love, betrayal and sacrifice.

| THE BRIDE FROM HADES (1968) |

|

In late 19th century Japan during the August Obon festival, a three-day period when ancestors are honoured and the spirits of the dead may return to the world, the members of a samurai family meet to discuss the fate of third son, Shinzaburo (Hongō Kōjirō). For them, the fact that that Shinzaburo lives amongst the poor and devotes his days to teaching disadvantaged children to read and write is bringing disrepute to a noble family. They thus believe that he should marry his late older brother ’s widow, Kiku (Uda Atsumi), a prospect that neither party appears to be remotely happy with. After defiantly saying his piece in his defence, Shinzaburo joins the villagers for an Obon ceremony in which the children carry lanterns to a nearby river, where they allow them to be carried away by the current in order guide the spirits back to their world. When one young boy ’s lantern becomes caught on reeds, Shinzaburo frees it for him, and he is just about to leave when he spots two other lanterns that have become similarly snagged. When he untangles them and sets them on their way, he is approached by beautiful Otsuyu (Akaza Miyoko) and her older companion Oyone (Michiko Ōtsuka), who reveal that the lanterns are theirs and thank him for his kindness.

A short while after returning home, Shinzaburo hears an unexpected knock at his door, and opens it to be greeted by Oyone, who once again thanks him for his thoughtfulness and requests that he grant her and her mistress an audience. When he invites them in, they tell him that that Otsuyu is also from a samurai family, but unfortunate circumstances saw her cast out by her relatives and sold to the Yoshiwara (a famed red light district) by a crooked moneylender. Due to skills learned as the daughter of a samurai, Otsuyu was able to achieve success as a courtesan whilst retaining her virtue but is now expected to submit to the carnal desires of a wealthy, elderly and lascivious client as soon as the Obon holiday concludes. Oyone reveals that Otsuyu has taken a liking to Shinzaburo and abruptly offers her to him, a request that startles and embarrasses the shy Otsuyu, but when Shinzaburo tells them of his work with the pure-hearted children of the poor and his ambition to open a school in the district, she eagerly hangs on his every word. As the women depart, neither they nor Shinzaburo realise that they are being observed by the drunken Banzō (Nishimura Kō), a deadbeat who works for and regularly scrounges off of the teacher. He recognises both women from the Yoshiwara and wonders why they would be visiting Shinzaburo, then realises that he could use this information to his advantage. Thus, the following day he flags down local gangster Rokusuke (Date Saburō), and over drinks tells him that he has information about a clandestine meeting that will interest his boss. When he reveals what he saw, however, Rokusuke laughs and tells him he must have seen ghosts, as both women died two years ago.

I have heard it said many times that if you want to tell a consistently compelling story, the audience should never be ahead of the characters. Of course, this is not the universal narrative truth that some have claimed, and The Bride from Hades [Botan-dōrō] is a prime case in point. You won ’t need to have seen (or, indeed, read) many period-set Japanese tales of the supernatural to realise in from the moment they first appear unexpectedly at the lakeside that Otsuyu and Oyone are not of this world, and yet the fact that Shinzaburo is blind to this does not work against the film in any way. In essence, his lack of awareness leans into Alfred Hitchcock ’s famed comment about how to build tension, the bomb under the table that the audience knows is there, but the characters are blissfully unaware of. The scenes that follow are thus not about whether the two women are ghosts, but how and when Shinzaburo will realise this fact and how deeply he will have fallen under their spell when he does.

The Bride from Hades was based on one of the most famous of all Japanese Kaidan ghost stories, Botan Dōrō (also the Japanese title of this film, and which translates as its more commonly known western title, Peony Lantern), which itself originated as a 17th Century translation of a collection of ghost stories by Chinese author Qu You titled Jiandeng Xinhua (New Tales Under the Lamplight). The story has undergone a few revisions over the years, and this celebrated film adaptation was apparently drawn primarily from what is known as the Otogi Boko version, but still goes its own way with some of the key story elements. As a ghost story, it gets off to a gentle start, with Otsuyu and Oyone presented as sympathetic human characters with no evil intent who seem instead to have targeted Shinzaburo because his earlier kindness indicates that he might be in a position to help them. Only when Banzō attempts to spy on Shinzaburo and Otsuyu in the throes of passion do the women openly display supernatural characteristics, with Otsuyu appearing spectrally skeletal to the terrified Banzō, who is then confronted with the floating and fearsome figure of Oyone, an image so unexpected and gloriously sinister that I genuinely jumped in my seat. Mind you, by then Banzō has already been given a serious fright when, after learning that Otsuyu and Oyone died two years earlier, he sees the face of the waitress who is serving him as a white mask shorn of all facial features except a downturned mouth. It ’s a superbly executed and genuinely jarring jump-scare that nonetheless makes little sense in the context of the story, unless of course the waitress is also a ghost.

There ’s more than a whiff of Mizoguchi Kenji ’s 1951 Ugetsu monogatari in Shinzaburo ’s attraction to the ghostly Otsuyu, and to that and the episode Hoichi the Earless from Kobayashi Masaki ’s 1964 anthology horror Kwaidan to the later attempts by local official Hakuōdō (Kurosawa favourite Shimura Takashi) to protect Shinzaburo and prevent the two women from entering his home. Once Otsuyu and Oyone’s ghostly nature is confirmed, and especially once Shinzaburo becomes aware of their true nature, the on-screen presentation of the women is subtly but unsettlingly transformed. The night of their third visit is a prime example, their approach to the house quietly announced by the karan karon clacking of their clogs, shifting then to a supremely eerie wide shot in which they are observed seemingly floating down the road towards us accompanied by Ikeno Shigeru’s ghostly score, their faces betraying their spectral true selves. When they reach the house, they glide around the outside in search of an open door, ultimate drifting in through a narrow gap and materialising before the startled Shinzaburo and behaving as if they were warmly welcomed in some time earlier. It’s after this that their voices undergo a small but chillingly significant change, their spoken words having a faint but dissonant reverberation, less an echo of what was said than an almost simultaneously delivered alternative reading of the same line.

This all contributes to a sense of steadily building dread so vivid that it seeps into every aspect of the drama, only to be then unexpectedly disrupted by the arrival home after a leave of absence of Banzō’s wife Omine, a loudly gregarious opportunist who is clearly used to getting her own way and whose scenes tip the film in the direction of broad comedy. Opinions will differ the wisdom of such a tonal switch at such a crucial stage in the story – it certainly threw me a little on my first viewing – but it does ultimately dovetail into the main story, as greed conquers fear and Omine pushes Banzō to cheekily strike a deal with the ghosts that stands to enrich them at the expense of their unfortunate neighbour. It should come as no surprise that they effectively seal their own fate with this bargain, but I was still caught out by the violent manner in which it concludes.

The Bride from Hades is an unpoetic English language title for a film whose supernatural elements work their magic not by hitting you in the face in the manner of modern jump-scare Hollywood horrors but by getting under your skin and chilling your bones. The decision to shoot even the exteriors on studio sets adds to the film’s otherworldly feel and allows Lone Wolf and Cub and The Snow Woman cinematographer Makiura Chishi free reign to create some hauntingly beautiful scope compositions. The building atmosphere of sinister dread is immaculately handled by director Yamamoto Satsuo and his talented cast and crew, and if you can deal with the unexpected late film tonal switch, the sequence that precedes it (and sets the scene for the couple's treachery) in which Otsuyu and Oyone glide desperately around Shinzaburo’s prayer-protected house in search of a way in is one of most tensely unsettling I’ve nervously watched all year. It also ties together those Freudian favourites of sex and death with the notion that a human could have sexual relations with a ghost, and even (once again, spoiler ahead, so skip to Sound and Vision section to avoid) slyly suggests that the death of the main character could have an upside if it means that he finds love and sexual fulfilment in the afterlife. I mean, if you have to go, there are certainly worse ways.

Both The Bride from Hades and The Snow Woman have undergone new 4K restorations, while The Ghost of Yotsuya was sourced from an HD digital transfer, and all three are presented in 1080p on separate Blu-ray discs and framed in their original aspect ratio of 2.40:1. And they all look terrific. Detail is really crisp and cleanly defined on all three transfers, and the contrast very nicely graded, with the solid black levels only softening a little on the darker scenes, presumably to avoid crushing shadow detail. There’s an earthy hue to the palette in some scenes, but the brighter colours, as seen on plants and costumes, are vividly rendered. Dust spots and damage have been almost completely banished (I spotted a couple of brief thin scratches but little else) and the image sits rock solidly in frame. The discs are encoded to regions A and B only.

The original mono soundtrack has been encoded as Linear PCM 2.0 mono on all three films, and while the tonal range on each is inevitably restricted, the dialogue is always clear, and the subtle ghostly echo of the voices on The Bride from Hades is most effectively reproduced. The loud treble-leaning sound that accompanies the Snow Woman on her first appearance is a little shrill, but there is no distortion, damage or obvious signs of wear to contend with, and the music scores are often tonally richer than expected.

Optional English subtitles are available for each film and are activated by default.

THE GHOST OF YOTSUYA

Kurosawa Kiyoshi (19:33)

J-horror pioneer and director of such genre masterworks as Cure (1997), Pulse [Kairo] (2001) and Creepy [Kurîpî: Itsuwari no rinjin] (2016), outlines why he regards Musimi Kenji’s Ghost of Yotsuya as the scariest film adaptation of this story, which began life as a kabuki play and one of the most famous of its kind in Japan. As I noted above, I find myself at odds with his view that what happens to Oiwa springs primarily from unfounded jealousy on her part, but he’s on the nose when he says that for the first two thirds it plays more like a relationship drama than a horror film, and when he notes how rare it is for an individual to transition into a ghost over the course of the narrative, as the ghost is usually already in existence at the start of such tales.

The Endless Curse of Oiwa (22:08)

A visual essay by Japanese film historian Hirano Kyoko that explores the evolution of Yotsuya Kaidan from its origins as a 17th century kabuki play through the various film adaptations over the years, including ones directed by such luminaries as Fukusaku Kinji (Crest of Betrayal / Chūshingura gaiden: Yotsuya kaidan, 1994) and Miike Takashi (Over Your Dead Body / Kuime, 2014). Unsurprisingly, the prime focus is Misumi Kenji’s take on the story, with discussion on the changes made for this adaptation, and key scenes that a Japanese audience would have known were coming and would have eagerly anticipated seeing. There’s no blaming of events on Oiwa’s jealousy here, with Hirano instead identifying a common trope in Japanese ghostly tales, where a wronged woman in a patriarchal society enacts revenge on the men who have mistreated her.

Trailer (1:43)

This original Japanese theatrical trailer is comprised of an almost randomly ordered collection of clips that include a few spoilers, albeit ones that would not have been spoilers at all to a Japanese audience of the day, given the fame on home turf of the story on which the film is based.

THE SNOW WOMAN

Ochiai Masayuki (15:50)

Director Ochiai Masayuki, whose many horror titles include the 2004 Infection [Kensen] and the 2008 remake of the Thai supernatural gem Shutter, explains the difference between ghosts and yokai, creatures from Japanese folklore that would, he suggests, include Yukionna in their number. He praises the way the film combines makeup, lighting and practical effects, and echoes my partner’s words with the observation that it’s mostly women who turn into ghosts in Japanese stories. He relates this to their oppressed role in a once heavily patriarchal society, noting pertinently that “Society behaves like a classroom bully and everyone becomes an accomplice by staying silent.”

The Haunted Mind of Lafcadio Hearn (6:47)

Asian cinema expert (and producer of what looks like all of the special features in this set) Tom Mes narrates this concise visual essay written by Lafcadio Hearn biographer Paul Murray, who provides a useful introduction to this hugely influential author and his work, from the early influence of various religions to his masterwork Kwaidan.

Trailer (2:16)

The original Japanese trailer is a scattershot collection of disconnected clips from the film, but given that this is ultimately a pitch for a supernatural tale, it ends superbly.

THE BRIDE OF HADES

Audio Commentary by Jasper Sharp

Critic, author, filmmaker and independent scholar specialising in Japanese cinema, Jasper Sharp, provides a considered and informative commentary on The Bride of Hades, a film he describes as more unnerving than jump-out scary, but also as a beautifully austere period film and more sophisticated that other horror movies of its day. He provides information on the then struggling Daiei studio, usefully clarifies some cultural and language elements of the film, profiles some of the actors, director Yamamoto Satsuo and screenwriter Yoda Yoshikata, and praises the beautiful cinematography and attention to detail.

Takahashi Hiroshi (17:39)

The screenwriter of the hugely influential J-horror Ringu (1998), Takahashi Hiroshi, discusses the Chinese origins of the story on which The Bride from Hades was based and its almost symbiotic relationship with the tale that inspired the similarly themed Ugetsu monogatari (1953). He recalls first seeing the film at a summer film festival and enthusing about it with Ringu director Nakata Hideo, talks about the film’s subtle use of wire work, speculates on how one eerie shot was achieved, and praises lead actress Akaza Miyoko, whom he believes was perfect for the role and of whom he says, “it’s literally scary how beautiful she is.” He also comments on the difference between the incorporeal ghosts of Japanese and British tales and the more solid apparitions of Latin countries such as Italy, and suggests that their Chinese equivalent is a combination of the two.

Trailer (2:24)

The original Japanese trailer is certainly creepy, but it cuts to the supernatural chase and reveals way too much, including the ultimate fate of the lead character. Save this until after your first viewing of the film.

Also included in the set is a Limited Edition 80-page Perfect Bound Book featuring new writing by authors Tom Mes, Zack Davisson and Paul Murray, newly translated archival reviews and ghost stories by Lafcadio Hearn, but this was not available for review.

Wow. If you’re already a fan of Japanese ghostly horror then this three-film set is an absolute must-have, and if you’ve yet to dip your toes into these particular genre waters then this trio of films makes for an excellent introduction. All three are superbly handled works with excellent production values and fine performances, and all succeed as supernatural tales not by delivering jump scares by the dozen but by slowly but surely burrowing under your skin in ways that stay with you for long after the films themselves have come to a close. Just today my partner asked me which of the three I liked the most and I found it impossible to choose, as all are excellent in the own specific ways, and the presentation on this three-disc Blu-ray set is exemplary. I know I have missed the release date by a couple of weeks (I was, after all, in the films’ country of origin for the whole of October), and so my recommendation comes late, but it’s a heartfelt and enthusiastic one nonetheless. No question, this has to be one of my favourite disc releases of 2024. Superb.

|