|

There's a moment in the opening scene of the 1970 Connecting Rooms that intrigued me in a way that I'm not sure was intended. As the unhappy-looking, middle-aged James Wallraven (Michael Redgrave) walks down a London residential road, dressed in a raincoat carrying a case in each hand, he pauses to look towards a boarding house window in a manner that informs us economically that he is looking for a room to rent. As he does so, the blonde-haired, female landlady pulls the net curtain back and smiles invitingly at him. Maybe it's just me, but what immediately came to mind was the Red Light district of Amsterdam, where the sex workers advertise their services by standing in the windows of the establishments in which they ply their trade. It's an impression given credence by James's response to this invitation, as he looks away in embarrassment an heads down the street to a more dilapidated building to try his luck there. As he's shown to his room by landlady Mrs Brent (Kay Walsh), he has brief encounters with two of the other residents, young aspiring songwriter Mickey Hollister (Alexis Kanner), and elderly concert cellist Wanda Fleming (Bette Davis). Wanda has the room adjacent to the one that James accepts, and he's not been installed long before discovering that the two rooms have a connecting door, one that can suddenly pop open under the slightest pressure. The first time this happens, Wanda seems keen to get to know her new, well-spoken neighbour, and while James is initially guarded in his response to her cheerful overtures, he slowly finds himself warming to her kindness, unaware that he's not the only one harbouring a secret.

As a quick aside, let's talk about the seemingly odd notion of connecting rooms, particularly as it manifests itself here. It's not that I'm unfamiliar with the concept, having seen enough films in which they play a key part in the establishment and development of relationships between the occupants of such interconnected lodgings. But with the exception of that sequence where the killers use them to get the jump on the cops early on in 48 Hrs. (1982), the majority of such rooms – at least in the movies – seem to be plush suites located in upmarket American hotels. I've only encountered this phenomenon in real life once, when I stayed for a night at a Holiday Inn near Heathrow Airport on my return from an overseas holiday. The room I was allocated had a connecting door to the adjacent one, and I have to presume that this was installed primarily to allow family members or friends to occupy adjoining rooms and move freely between them without having to step out into the corridor. When the rooms are occupied by two strangers, it's a different story. I found myself wondering whether the door in question could be opened by my neighbour, which in turn made me wonder how safe my possessions would be when I went out for dinner. It also proved to be the weak spot in the room's otherwise effective sound insulation – I could hear my neighbour's TV clearly through the door, and just about everything else when it was switched off, if you get my drift. The connecting rooms in the film bearing that name are situated in a boarding house in 1970 London, and not only is the door between them not locked, all it takes is a gust of winding to push it open. Anyone occupying either room would have free access of the day to the one next door, and considering how prissy landlady Mrs Brent is about what happens in her rooms, and that she secures all the rooms from the hallway with locks, it seems odd that she ignores this massive flaw in the security of two of them. And this door, unlike the far more robust one in my room at the Holiday Inn, appears to be surprisingly good at noise insulation, despite the sizeable gap between the base of the door and the floor. Am I being too picky? Don't answer that. Now, where was I?

Had I not been informed of the fact by the opening credits, I would not have been surprised to learn that Connecting Rooms was adapted from a stage play. It is, after all, driven almost exclusively by conversations and encounters in largely static locations, usually between two people at a time, until disrupted by the arrival of a third party. Even the title has the ring of a play by someone like Terence Rattigan or Alan Ayckbourn – a tad ironic, then, that this was the invention for director and screenwriter Franklin Gollings, as Marion Hart's source play was simply titled The Cellist. I was just feeling guilty at never having heard of it when I discovered that it was never produced or performed. I also came to the film knowing nothing about Franklin Gollings, whose only dramatic feature this proved to be as director. The two short films included in this disc's special features and the detail provided by accompanying booklet proved to be most enlightening on this score.

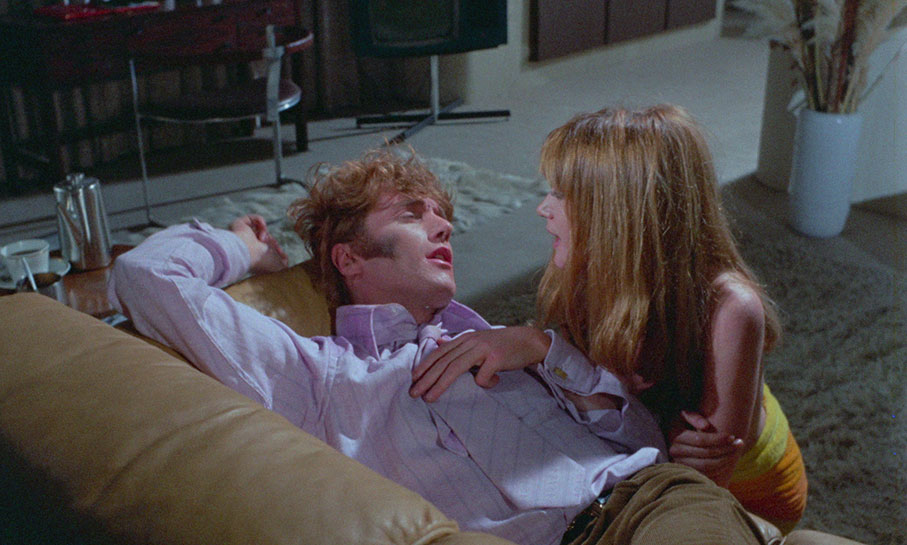

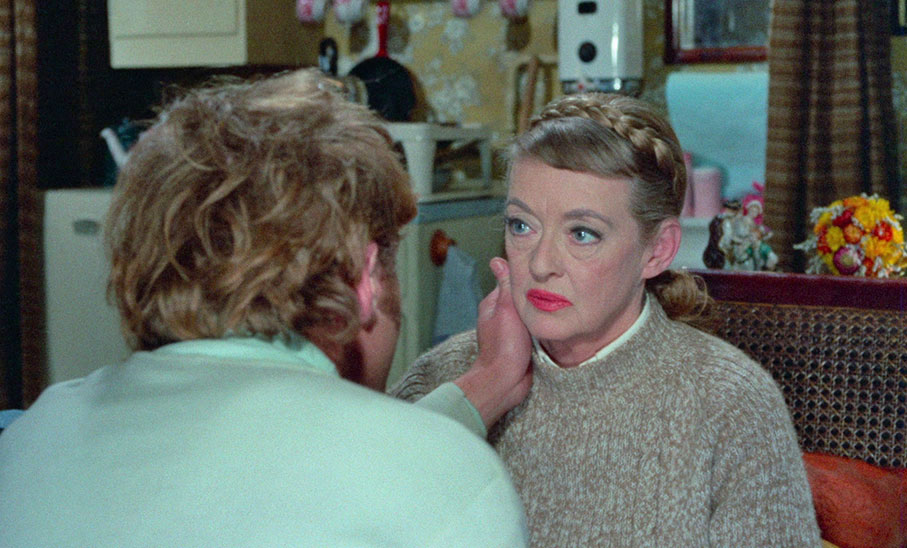

As indicated above, the story is driven almost solely by its dialogue and characters, and fortunately the latter all prove individually distinctive and intriguing in their own way. James is clearly carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders from the moment we first meet him, and while he at first appears to be taking a long-needed break from the pressures of his job as a school headmaster, it soon becomes clear that the source of his malaise is something altogether more serious. Wanda initially comes across as the complete flipside of James, a lively ball of positivity who seems keen to make friends with everyone, except for the nosey and cantankerous Mrs Brent, whom she seems to rather delight in winding up. Yet it soon becomes evident that Wanda's gregarious nature is rooted in a desperate loneliness, and that she'll do almost anything for a few moments of friendly companionship. Taking full advantage of this is Mickey, an amoral opportunist who is leeching off Wanda by pretending to romance her, despite being something like 40 years her junior. He simultaneously maintains a relationship with his girlfriend Jean (the delectable Gabrielle Drake), then puts her on hold in a heartbeat to woo visiting French singer Claudia (Olga Georges-Picot), but only so he can convince her to record a song he has written, which he sees as a path to personal fame and fortune. Quite why Claudia responds to his advances is a bit of a head-scratcher, but in a rather nice bit of gender stereotype reversal, it's she who proves to be the most amorously forward to the two, eventually seducing the reluctant and now booze-weary Mickey, who just wants to lie down and go to sleep. Although kept busy juggling his time between Jean and Claudia, he continues to take advantage of the sadly smitten Wanda, which throws a potential spanner into the altogether more genuine friendship that is developing between her and James. When Mickey marches on the two as they are taking tea in Wanda's room at one point, the delighted Wanda immediately turns her attention to him, which prompts the shyly uncomfortable James to retreat to his own room. The urge to lean into the screen and slap this self-centred git six ways from Sunday was by this point becoming increasingly hard to resist.

The stage play origins of Connecting Rooms are also evident in other ways. Although heavy on dialogue, it is well written, but does lacks the sort of standout exchanges and monologues that elevate some stage-to-screen adaptations to a higher tier. I'm guessing the number of locations has been expanded from Marion Hart's play, but the film still has a very enclosed feel, although this does add an intriguing spin to the title, with the various rooms in which the story plays out all interconnected through the characters story arcs.

Solidly written stage adaptations do sometimes bring out the best in the actors they attract, and that's certainly the case here. It's the subtlest of work done by Bette Davis and Michael Redgrave as Wanda and James that really engaged my sympathies, with both actors getting beneath the skin of their characters in a way that makes the developing friendship between them both believable and touching. Their final scene together, and particularly the knowing looks that pass between them, genuinely brought a warm glow to my stony old heart. Working as well but in a different vein is Alexis Kanner, whom we all have a soft spot here for his iconic role as The Kid in The Prisoner. As the infuriating but oddly enigmatic Mickey, he is simultaneously charming, egocentric and duplicitous in a way that may or may not have been intended to be read as symptomatic of his generation. I'd happily have watched more of Gabrielle Drake's radiant but increasingly frustrated Jean, and if you only know her for her role as purple-haired Lieutenant Gay Ellis in Gerry Anderson's UFO, get ready for a surprise in the mid-film art class scene.

Although it does deal with adult themes, Connecting Rooms is a sometimes rather cosy and very British affair, whose most startling secret has had its impact considerably watered-down by the passing of time and the plethora of considerably more outrageous scandals involving public figures that have hit the headlines since the film was made. Despite its brief dip into the filmmakers' idea of what constitutes swinging London, it often has the feel of a film made in the late 1950s, a sensation enhanced by John Wilcox's Technicolor cinematography. Indeed, so convincing is this period feel that the groovy nightclub scene and the documentary footage of a real-world anti-war demonstration (one that then breaks into a staged riot) make it almost feel like a 50s drama that intermittently makes ten-year hops into the future.

For all that, Connecting Rooms is an easy film to like, if not one I found myself getting particularly fired up by. I certainly enjoyed my first two viewings and am glad to have had the chance to see it (hats off once again to Indicator here), and have a feeling that it may just grow on me further with the passing of time. I can definitely see myself revisiting it at a later date, if only to watch Davis and Redgrave at work, as despite solid direction and the high standard of the acting all round, it seems only appropriate that it's ultimately their movie.

As a final side note, my research suggests that Davis's seemingly impressive cello playing skills were faked by a clever bit of costume and lighting work. From what I'm, able to deduce, British classical cellist Amaryllis Fleming sat directly behind Davis and threaded her arms through the modified top that the actor is wearing, replacing the arms of the actor in a way that gives the impression that it's Davis who is playing the cello. It may sound a little had to swallow on paper, but the effect is surprisingly convincing on screen.

Sourced from a 4K restoration by Studiocanal, the 1080p, 1.66:1 transfer here is generally very pleasing, and certainly captures the Technicolor look that visually aligns it with other British films of the late 1950s. The skin tones have a slightly artificial hue, but one that is consistent with other Technicolor films of this period, and brighter coloured costumes and décor are vividly reproduced. The contrast is pleasingly graded, and while the black levels are generally solid, they do soften a bit in darker scenes to retain shadow detail. The image is crisp and the detail well defined, and picture as a whole has the sort of richly filmic look that I have still yet to see reproduced on digital formats. As expected, the transfer is clean of any dust or signs of wear.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack has the sort of narrow dynamic range that adds to its period feel, but not in a detrimental way. Dialogue is always clear, and Joan Shakespeare's music score comes across well enough. There are no obvious signs of wear here, and even when I cranked up the volume I heard no background hiss.

Optional English subtitles are available for the deaf and hearing impaired.

The John Player Lecture with Bette Davis (32:06)

An audio recording of an on-stage interview with Bette Davis, conducted by Joan Bakewell in 1971. It does appear to have been edited, presumably to remove screened film clips and their introductions, the inclusion of which would have caused copyright issues and made less sense anyway in an audio-only extra. With so many films on her CV and an interview running time of about half-an-hour, it's inevitable that only a few of them get coverage here, but there are engaging stories about Jezebel, Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, All About Eve and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane, and some interesting recollections of how the studios tried to shape the look of some of their female stars. It's often a fun listen and Davis is on lively form, whether providing serious answers to Bakewell's questions or amusing responses to ones from the audience. The best of these comes when one male questioner opens with, "Miss Davis, something I've wanted to ask you for thirty years," to which Davis responds enthusiastically, "To marry you?"

Theatrical Trailer (2:57)

Not the most convincing of sells really hammers home the generation gap-clash that pits middle-aged characters against swinging 60s London before dissolving into a series of strung-together shots that hint at the story without getting too specific. It's narrated by our old friend, Patrick Allen.

Image Gallery

30 screens of promotional photos (including a sprinkling of glamour shots of Gabrielle Drake), lobby cards, press pack scans, and a single poster.

Bette Davis Eulogy

A transcript of a speech – first broadcast on Clyde Radio on 11 October 1989 – delivered by Franklin Gollings shortly after Bette Davis's death. He recalls first falling in love with the movies via Lon Chaney's now lost London After Midnight (my jealousy here knows no bounds), and eventually meeting and working with Davis on Connecting Rooms, He also has a story about a special screening of the finished film, and Davis's reaction to it. This is presented as typed text, two columns per page, over seven screens, which are advanced manually.

Spotlight at the Fair (1951) (18:26)

A documentary short from the Spotlight series, directed by Franklin Gollings, which takes a look at travelling fairs in the UK, as well as the larger-scale attractions on Blackpool's famous Pleasure Beach. Although in the mould of many an info-short made for public consumption, this is really well assembled, thanks in no small part to Robert Johnson's snappy editing and Ian D. Struthers cinematography, which is peppered with eye-catchingly framed shots and even includes a few POV shots taken on the various rides. The process of taking a travelling show's attractions apart for transportation is eye-opening (think dismantling and loading an entire bumper car arena onto trucks), and I did smile at thrill-promising signs like "See the ram with five legs and six feet alive!" and a similar one for a dog-faced monkey.

The Way to Wimbledon (1952) (17:00)

Another documentary short directed by Franklin Gollings, this time for Pathé and narrated by (or, as the credits here have it, 'described by') renowned actor John Mills. This one takes a look at the annual Wimbledon tennis championship, its preparations and the work involved in maintaining the grounds and running the competition. As someone with no interest in tennis whatsoever, I have to salute a documentary made about it that manages to hold my attention, and that's certainly the case here. I will admit that I found the behind-the-scenes look at the work of the groundskeepers and competition support staff a lot more interesting than the airy hopes and dreams of the young tennis players, but the film gets the balance between the various aspects about right – even the process of selecting who will be invited to participate proved educational to this sport-averse viewer. Once again, the film is smartly photographed (this time by George Stevens) and edited (by Terry Trench), and is briskly marshalled into an informative and engaging whole by Collings, more of whose short films I'd now rather like to see.

Booklet

Following the credits for the main feature, the lead essay here is by film and media lecturer Laura Mayne, and provides a useful overview of the production, the actors and the director. Extracts from a 'fact sheet' included with the film's press kit that explore the film's characters, actors, story, and themes are followed by a 1969 Daily Mirror piece on a party hosted by Bette Davis for colleagues and the press following the completion of Connecting Rooms. Next is a most welcome 1971 interview with Franklin Gollings by Linton Mitchell of the Reading Evening Post (hats off to the researchers for locating this), in which he talks about his early work and the production of Connecting Rooms. Extracts from three contemporary reviews of the film follow, two of which are critical, the other more positive, and rounding things off are credits and overviews of Spotlight at the Fair and The Way to Wimbledon. As ever, the booklet is attractively illustrated with promotional material.

Generation gap dramas of the late 1960s and early 70s often seem retrospectively hamstrung by the fact that they were generally made by middle-aged establishment figures with little understanding of the youth-driven societal shift that they seemed to distrust or fear. There's certainly an element of that in Connecting Rooms, albeit one that is balanced a little by James' fiercely expressed belief that the student protests are fully justified, something that blows up in his face in one of the film's few less-than convincing scenes. It's no lost masterpiece, but is still an enjoyable and ultimately involving slice of cinematic theatre whose performances alone make it worth hunting out. Indicator's Blu-ray sports an excellent transfer and some worthwhile special features (I particularly liked the two Franklin Gollings documentary shorts), and it thus comes warmly recommended.

|