|

| Part 2: The Films and Disc Details |

|

1. Post Haste (1934 – 8:43)

Made soon after Jennings joined John Grierson's GPO Film Unit as a raw recruit, Post Haste was the first of three educational films made by Jennings for screening in schools. It recounts the history of the Post Office, from its establishment in 1635 to the 1930s, using two-dimensional visual material provided by the British Museum and the Postal Museum, material brought to life by some nifty camerawork. Delivery was initially a noisy undertaking. Letters, we are informed, were first carried between 'posts' by mounted post-boys, each briefed to "blow his horn as often as he meeteth company or passeth through any town, or at least thrice in every mile." Initially based in Lombard Street, in 1829 the GPO moved into a neoclassical building designed by Sir Robert Smirke, who also designed the British Museum. This new building on St Martins-le-Grand was, it was felt, "more worthy of British commerce...more honourable to British tastes and British opulence." We see the early days of highway robbery, the gallows, and "the Express Extraordinary" – a civilian service that, extraordinarily, carried military despatches. Junk mail was obviously a feature of the postal service even then; we 'watch' sacks stuffed with copies of The Gentleman's Journal being loaded onto carriages, before learning that it was not until 1902 that horses were superseded as the main means of delivery. The film ends with footage of the vans and trains of the 'modern' service.

2. Locomotives (1934 – 8:43)

Opening with a jaunty piano accompaniment redolent of silent cinema, the film begins by illustrating the principle of steam power with the use of a boiling kettle. The history of the train is traced from its humble origins in collieries, through to the arrival of Stevenson's Rocket and the spread of the railway network. The Darlington to Stockton line was opened in 1825, the Liverpool to Manchester route in 1830, before Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester are finally connected to London in 1839. The models used in the film were shot in close-up, on location at the Science Museum in South Ken. They are by turns Thomas the Tank Engine basic and impressively intricate. The camerawork, sadly, is never more than basic and the camera even slips out of focus occasionally, reminding us that Jennings was learning on the job, and needed to. Basic though the film is, it provides an early indication of Jennings' fascination with trains and with technology.

3. The Story of the Wheel (1934 – 12:04)

This film feels as if it were Jennings' first effort, it is certainly his least successful. The last of his three films for schools, it features one of the most annoying voices ever recorded. The female narrator tells us, in her shrill twang, that primitive man "carried his prey on his beck, for he had not discovered that animals could be used for other purposes beside food." The voice first tells us how the wheel was invented, then recounts the fascinating history of Britain's roads. The Romans were the first to make roads scientifically, the Normans were too busy making castles to worry about roads, and in the 12th to 15th centuries goods were transported by pack horse and barge. The 17th Century saw the appearance of the first, fine English carriages, very "feshionable" Lady Muck tells us. In 1673, it took eight days to travel from York to London but, fortunately, carriages became "fester and fester." By 1730, the journey could be completed in three days, by 1800, with a relay of horses, in 20 hours. The transfer from horse power to steam power revolutionised travel. The information delivered is fascinating but the production standards are, literally, comical. In one hysterically funny scene a twig attached to a piece of twine is dragged across a model landscape, perhaps by Jennings himself, to demonstrate...what? I forget; you'll have to excuse me, I was too busy laughing.

4. Farewell Topsails (1937 – 8:51)

This charming, touching film represents a quantum leap in Jennings' skills as a filmmaker. As the film begins, Will, a talented accordion player, "grinds out his haunting old tunes to an audience that is composed of the last survivors of a great race of seamen." Will now works as a miner, in the pit at St Austell, Cornwall. The area produces "the best clay in the world" and is home to the china clay industry. The clay is shipped aboard topsail schooners to paper mills at the mouth of the Thames, or else to Runcorn, near Liverpool, and from there, by barge, to the Potteries. As Will hammers out a rendition of "My Bonny Lies Over the Ocean," and men without a ship gaze on wistfully, The Alert sets sail on her regular run from Foy to London, her patched up sails billowing in the breeze. Her skipper, Captain Dudbridge, runs her at a loss because he can't bear to see her hauled onto the mud to rot like other schooners have been. Jennings is reminding us, here, of the human cost of technical progress. Farewell Topsails is beautifully made, melancholic, and gently moving. It reminded me of a poem written by an anonymous merchant seaman: "What was the secret of those splendid things/Whose passing filled mankind with vain regret/Those soaring pyramids of snowy wings/Where use and art in such sweet concord met/I only know the thought that comes to me/Of something precious vanished from the sea."

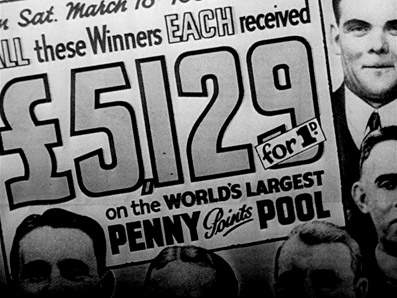

5. Penny Journey (1938 – 5:53)

Penny Journey – The Story of a Post Card from Manchester to Graffham, to give the film its full title, contrasts urban and rural English life, while tracking a postcard sent by a boy in a street of two-up-two-downs to his aunt – Mrs Thorpe, Tegleaze Farm, Graffham, Nr Goodwood, Sussex. His message to her is short and sweet: "Dear Auntie, Thank you very much for your letter. It must be nice to be in the countryside." Ar, bless im. The film is short and sweet too, while delivering detailed information with the same admirable efficiency displayed by the Post Office.

6. Speaking from America (1938 – 10:24)

Once again, Jennings delivers information in snappy, quick fire style, explaining the physics behind telephone communication effectively, if remorselessly. A businessman in London makes a call to Lawrenceville, New Jersey, and we follow his voice on its journey across the Atlantic just as we followed the postcard across England in Penny Journey. His voice is transferred from the local exchange to the GPO's flagship Faraday Building on Queen Victoria Street, which in 1933 had become the telephony centre of the world. From there his voice proceeds to Rugby, where it is magnified 120 million times, before being sent to the shortwave radio station that transmits it, by means of a system of aerials, known as Arrays, in the direction of New York. His colleague's reply is later received in Baldock, before being forwarded to the radio receiving station on Canvey Island. To demonstrate the power of transatlantic communication, the film ends with a broadcast by Roosevelt that prepares the way for war: "A few days ago a whisper, fortunately untrue, raced around the world, that armies, standing over against each other in unhappy array, were about to be set in motion. Your businessmen and ours felt it alike, your farmers and ours heard it alike, your young men and ours wondered what effect this might have on their lives." They did well to wonder.

7. The Farm (1938 – 12:58)

Springtime arrives on a farm in fictional Wessex, made famous by Thomas Hardy. Lambs and piglets gambol on the grass, free-range and content, picked out in their frolics in glorious Dufaycolor. The film's intention, besides its main one of promoting Dufaycolor, seems to be to remind us how important food is, while being jolly and entertaining. Tabby and Ginger are famished, sheep butt each other to get at the food laid out in troughs ("There's one old lady who's already booked a place in the queue."), the horses are hungry ("Their tummies will soon be crying 'cupboard'."), lambs are fed from a bottle ("Now you know what it means to take to the bottle."). As to the pigs and piglets, they are both hungry for food, and soon to be food ("It's sad to reflect that these youngsters do themselves so well now, so that we can do ourselves well later on."). The farm workers seem more interested in the free beer. Cheers! It is hard to know how Jennings arrived at this subject matter, but easy to see, again, his interest in another vanishing way of life. One ominous, curious comment, tossed off as an aside, stops us in our tracks, and seems designed to calm jitters. This, we are told, is "A peaceful scene, where thoughts of war and rumours of war have no place. Whatever may happen to us, nature has decreed that seedtime and harvest continue their unending round." Like English Harvest, the shorter version of the film, The Farm presents the countryside as tranquil, peaceful, dependable, stable, and wholly wholesome, rooted in the past but vital to the future. This amusing, colourful distraction reveals a couple of things about Jennings, his interest in the detail of working life and his respect for the farming community's ancient skills.

8. Making Fashion (1938 – 15:11)

If you love dresses, you'll love this film. There are dozens of dresses on display, 20 minutes worth of dresses, dresses with exotic names, dresses made from exotic animals, dresses made from all manner of materials, but, most importantly, dresses of various shades and – Dufaycolor – colours.

9. Spare Time (1939 – 14:29)

This influential, brilliant survey of the leisure time habits and hobbies of the pre-war industrial working class is the most important film in this first volume, and stands as an important record of yet another vanished way of life. Indebted to Jennings' work on Mass Observation, this is Jennings' first successful use of collage, and what a collage. We see folk acting, cycling, dancing, marching, rambling, singing, playing cards and darts, tending to pigeons, mending bicycles, walking dogs, watching the wrestling and football, folk at the zoo, at home eating 'Desperate Dan pies' fresh from the range, at home reading The Daily Herald ("Her Scent Was Bat's Delight"!), down the allotment or down the pub. The film oozes the energy and enjoyment of life of its subjects. Richard Cobden looks down disapprovingly from a pedestal in a park. It's an image reminiscent of that which Andrew Higson's suggests as an iconic definition of Kitchen Sink Realism: "That Long Shot of Our Town from That Hill." There aren't many activities left out of the film that could be shown, though the absence of cinema, reading and politics is striking. Scott Anthony, in his liner notes, tells us that art historian David Mellor regarded Spare Time as displaying "the strongest concentration of pop iconography in any work by a British artist until the emergence of Tom Philips and the Independent Group in the 1950s." This from a film made during a period when the working classes were almost completely excluded from our film culture. The film ends with a reminder that life isn't all play, as a group of miners clock on to the night shift. The film has its critics. The scene involving brass bands and kazoo bands were deemed to be patronising by those unfamiliar with that tradition. As Keith Beattie says, "Criticisms of Spare Time failed to recognise that Jennings' depiction of working-class life was a sympathetic one, attuned to issues of communal solidarity and regional identity.

7. SS Ionian (1939 – 20:29)

A GPO film designed to reassure the public that His Majesty's navy is patrolling the high seas, this film takes us on another journey, with the Steam Ship Ionian, from Gibraltar, across the Mediterranean, via Cyprus and Malta to Alexandria and Haifa. This is another film remarkable for the detail Jennings packs into it. It is also fascinating for its footage of the ports visited along the way. Cargoes, the alternative version of the film included among the extras, makes the message of the imminence of war more explicit. Just as well that it did, for war was declared shortly after the film was completed. Jennings had unwittingly filmed the Ionian's final peacetime voyage. Although she survived the war, she ultimately shared the same fate at the beached schooners that featured in Farewell Topsails, being broken up for scrap in 1967.

8. The First Days (1939 – 23:09)

Made, like London Can Take It!, by Jennings with Pat Jackson and Harry Watt, The First Days is an impressionistic account of the early days of the war. After John Grierson's departure for Canada, the GPO Film Unit was left leaderless. It drifted, rudderless, for a while. Even when war broke out, and the Ministry of Information was formed, there was no move to put the filmmakers of the Unit to productive use. Harry Watt, recalling that time of inactivity during the period colloquially called "The Bore War," says: "Nothing happened for six weeks. We sat on our backsides looking out of the window, watching the tarts in Savile Row." When Alberto Cavalcanti took a unilateral decision to put them to work, all the filmmakers of the Unit shot footage. The result is a wonderful film entirely, partly accidentally, in keeping with Jennings' commitment to collage. The film assembles riveting footage of Londoners preparing for the worst by fortifying their city with sandbags; children, pets and paintings being evacuated; the training of young recruits and civilian volunteers to face war. As Lindsay Anderson says, the film "captured – in the plain, ordinary faces confronting catastrophe – the poetry and pathos that Jennings in particular was to make memorable in his later work."

9. Spring Offensive (1940 – 20:01)

Spring Offensive is a slightly stagey film made to extol the virtues of War Ag's work in reclaiming unfarmed or derelict arable land. This was necessary in response to the desperate need for an increase in food production and because of a lack of available labour. The film records the arrival of reinforcements in the form of machinery and the Women's Land Army, which had been formed in 1939. "Many of colts have joined up, so the fillies come to the rescue!" Set in Suffolk, not far from Jennings' native Walberswick, the film also presents a rosy picture of evacuation, suggesting that evacuated children integrated easily into the lives of their host families and the life of the countryside. The film represents Jennings' first use of dramatised re-enactment and it isn't entirely successful. Jennings' interest in machinery is apparent throughout. The film ends with a plea to posterity not to forget rural England: "Remember, we've looked after the land properly only during periods of war...Now the countryside asks you to do something in return...When peace comes, don't forget the land and its people again."

10. Welfare of Workers (1940 – 8:48)

The film begins by proclaiming the advances made by organised labour and concludes by suggesting that everybody was happy to surrender hard-won industrial rights. As Kevin Jackson points out, the film's hidden agenda was to persuade socialists to support the war effort. This is the most blatantly and straightforwardly propagandistic of Jennings' films. An army of factory inspectors, we are assured, will ensure that working conditions are of an acceptable standard. Young women can also rest assured that, should they venture forth after being called up for factory work, conditions will be so impressive that they will feel they have stepped from the 19th into the 20th century. The film ends with footage from a works canteen, in which Minster for Labour Ernie Bevin gives a pep talk to a group of slightly sceptical workers. We'll win, he says, and we'll win cheerfully. What's more, "We won't have to order very much. We'll all go along together."

11. London Can Take It! (1940 – 9:21)

The message London Can Take It! sent to its intended US audiences was: 'We'll keep our end up but it'd be nice to have some help'. There is a hint of disapproval in Quentin Reynolds' voice when he says: "These are not Hollywood sound effects. This is the music they play every night in London – the symphony of war." The film was hugely popular in the States and had a significant impact on public opinion there. It might be argued, therefore, that the film constitutes the single most successful piece of propaganda produced during the war, as well as the most beautiful. Meanwhile, the message sent to those at home by Britain Can Take It is spelt out on a huge poster adorning a building in Covent Garden: "Carry on London. Keep Your Chin Up!" Despite the film's insistence that "London is not taking its beating lying down," it was criticised for an overemphasis on stoicism at the expense of belligerence. Harry Watt certainly felt so. He recalls: "We were getting very tired of the 'taking it' angle." Watt promptly made Target for Tonight (1941), his film about a Bomber Command raid into Germany, in order to rectify that perceived imbalance.

Note: This is a dual format release containing both DVD and Blu-ray discs, but this review was based solely on the Blu-ray.

The fact that this collection is being released as a dual format package – and thus includes high definition transfers of all of the films on Blu-ray – will inevitably play on expectations for what the format can deliver. It is, however, important to remember what we are dealing with here, seventy year-old public information films whose restoration did not extend to the sort of frame-by-frame clean up employed by the likes of Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung. It's thus hardly surprising that none of the films are in pristine shape, and that scratches, dust spots and other damage are sometimes commonplace, though the situation does improve as the production timeline progresses. Dufaycolor may well have looked rather nice in its day, but time has drained most of the films shot using this process of most of its pigmentation, with only The Farm still looking like it was actually shot in colour rather than tinted in post-production. What does impress is the generally well balanced contrast range (there is some flickering typical of films of this vintage) and the sometimes eye-opening level of detail – while this is something you should expect of any film shot on 35mm, it's a sharpness that we're not used to seeing on films of this genre and vintage. The image quality on sunlit exteriors in films such as Speaking From America and Welfare of the Workers is often exceptional.

The only gripe I originally had was a very visible patterning on the Dufaycolor films, particularly Making Fashion and The Farm, something I wrongly put down to digital enhancement, a supposition that was corrected by Doug Weir of the BFI's Technical Department, who provided this useful and detailed explanation of the cause of this patterning:

In fact no digital enhancement was used on any of the films in this set. The visible patterning is very typical of the films made using the Dufaycolor process. Dufaycolor is an additive lenticular colour process that utilizes the combination of the three additive primary colours, red, green and blue, in a geometric pattern or mosaic applied to the film base which is visible when projected. Dufay colour was primarily a process for creating photographic transparencies/slides but was eventually developed for the motion picture market. It's because of the visible mosaic patterning (even if quite striking) that Dufay never made it as a major colour process (only two British feature films were ever made).

Intriguingly, the patterning is apparently only visible at all due to the increased resolution that Blu-ray allows and is almost invisible on the standard resolution DVD.

The PCM mono soundtracks are also victims to age and the ravages of dust and storage conditions, with plenty of crackle and a few lively pops on the earlier films, though the volume of this background wear-and-tear once again decreases as the timeline progresses. The narrow dynamic range is par for the course, but there is an unexpected level of clarity to narration and music and none of the distortion you might expect from the latter.

I have already covered the films below, above, but it is worth reiterating that they offer valuable insight into Jennings' development. The Birth of the Robot is a startlingly inventive, if kooky experiment in early animation, and, if we take time to compare the alternative versions here with their counterparts, we learn much about the inner workings of Jennings' creative mind.

The Birth of the Robot (1936 – 6:44)

English Harvest (1939 – 8:57)

Cargoes (1940 – 9:23)

Britain Can Take It! (1940 – 8:16)

Booklet

The British Film Institute, as repository of our national store of moving image treasure and knowledge, can always be relied upon to produce lavish, painstakingly researched booklets to accompany their releases. This one opens with an excellent essay by Mary-Lou Jennings and continues with another on Jennings by the peerless Julian Petley. Each film receives its own compact essay and full production credits are included, along with evocative stills.

The BFI's release of The Complete Humphrey Jennings is an important cultural event. Everyone who admires Jennings, all who love film, even anyone interested in England, will regard it as an essential purchase. Volume One: The First Days contains 15 films, including previously neglected or unavailable work, and an authoritative booklet. It represents incredible value for money. The quality of the films assembled in this first volume is, it must be said, patchy. Given that Jennings was a filmmaker developing his craft and prepared to takes risks, one or two of these films are feeble, as one would expect. Fortunately, they are all fascinating, and two or three are sublime. Humphrey Jennings is one of our great directors, and when this volume is added to the imminent second and third volumes, owners of the complete collection will count themselves blessed to hold in their hands the full body of his work, one of the great achievements of cinema.

<< Part 1: An Overview

|