| |

"Whenever I go to the cinema I'm always more interested in the girl at the box-office than in the film." |

|

Federico Fellini |

Although it's easy to mock (and I've been known to do it myself on more than one occasion), it's hard not to read a whole string of suggestive meanings into the deceptively straightforward opening shot – a subjective camera viewpoint of a train entering a darkened tunnel – of Federico Fellini's surrealistic fantasy City of Women. It transports us through a doorway from the waking world into a dream; it's a journey down the rabbit hole to a twisted Wonderland; it's the famed example of Freudian penetration symbolism that provided North by Northwest with its outrageously cheeky ending; it's a journey from a masculine light into a proto-feminist darkness; it's a descent into a hypnotic state in the psychiatrist's chair. Think I'm being fanciful? Take a look at the film first then re-examine that list and tell me I'm wrong.

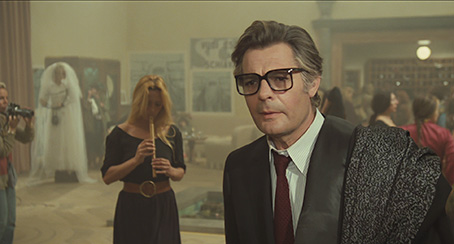

The man on the psychiatric couch here is middle-aged Snàporaz, engagingly played by Fellini favourite Marcello Mastroianni, who wakes from a motion-induced train carriage snooze to find himself sitting opposite an unknown but alluring woman, with whom he becomes entranced enough to follow to the train's toilet and hungrily grope. When she appears to respond positively to his sleazy advances, he follows her off the train and into a forest, in the midst of which is an anachronistically located hotel overrun by women attending a feminist convention.

Now some of you younger souls unfamiliar with what it once meant to be a committed feminist may wonder quite what is going on here. City of Women was released back in 1980 at the tail end of a period of assertive political action and protest by women who were sick to the back teeth of being treated as second-class citizens by men. And with damned good reason. They were paid less for doing the same work as their male colleagues (many still are), regularly objectified in demeaning ways (ditto), and rape victims were portrayed, even by supposedly neutral judges, as willing provocateurs who encouraged attacks though the manner in which they behaved and dressed. In this country it wasn't until the mid-1970s that it became illegal to discriminate against women in work and education, or illegal to sack a woman because she was pregnant. As recently as 1970, working women were refused mortgages unless they could secure the signature of a male guarantor, and it was another ten years before any woman could apply for a loan in her own name rather than that of her husband. I could go on. The political activism that made the 60s and 70s so special prompted sometimes angry responses both in Europe and America, one of the most extreme being The SCUM Manifesto drawn up by radical feminist Valerie Solanas (SCUM being an acronym for 'Society for Cutting Up Men'). The document called for women to "overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and eliminate the male sex." In 1968 Solanas did her bit for the cause by shooting celebrated pop-art superstar Andy Warhol in the chest. She later blamed her failure to kill him on her lack of target practice.

If Solanas was the extreme face of radical feminism, you didn't have to look far in the mid-to-late 70s to find women almost as angry about their unfair treatment by what was still very much a male dominated society. As a collective they upset and alarmed male traditionalists, who liked their ladies docile and didn't know how to handle women who were more forceful and articulate than them. And so was born the media-led mockery of feminism, in which such women were painted as ugly and aggressive man-haters who had taken to feminism because no guy would touch them. Men really were pigs. I'm not sure we've improved much in the subsequent years.

The feminists conferencing at the Grand Hotel Miramare are clearly shaped just a little by this paranoid male viewpoint, dressed-down women enthusiastic and even dogmatic in their determination to combat patriarchal oppression of the very sort practiced by the venerable Snàporaz, who chases after the woman on the train not because he's dazzled by her wit or even her beauty, but because he's mesmerised by the size of her arse. As he slowly makes his way through this lively throng in pursuit of his elusive quarry, there's almost a whiff of The Birds about it – you suspect that if Snàporaz does or says one wrong thing then these distracted women will suddenly stop what they're doing and verbally (or perhaps physically) tear him to shreds.

Much like Guido (also played by a spectacled Marcello Mastroianni) in 8½, the consensus seems to be that Snàporaz has been cast as Fellini's alter ego, allowing him to explore how his own lifelong fascination with women was effected by his fears and insecurities about the rise of feminist thinking. This is most starkly realised when he escapes from the house on the back of the motorbike of a homely woman (given how many women are in the film, it's surprising how few have been given character names) whose very direct attempt to seduce him he actively resists. Why? Well, she's about his age, on the rotund side and not classically pretty. Hmmm. Escaping her clutches, he finds himself in the company of a carload of distracted teenage girls, who behave irresponsibly and lose themselves in the rhythm of electro-beat music, and is soon being stalked on a dark road swathed in Hammer-esque fog by the dual threats of gender and the generation gap.

He's rescued by Katzone, a grotesque caricature of archaic alpha masculinity (his name apparently means "big cock", and we're not talking farmyard poultry here) whose house is littered with mechanical erotica and audio-visual trophies of his plethora of past conquests. Initially Snàporaz feels at home in his company, intrigued by his artefacts and a mausoleum wall of pictures of women he has bedded. It doesn't last long. A party thrown by Katzone to celebrate his ten-thousandth sexual partner (don't even try to do the maths on this one) is tainted for Snàporaz when his wife Elena shows up and has a good time, prompting a heart-to-heart that forces him to confront, if not conclusively respond to, his failings as a husband.

From here on in the tone starts to darken, as a storm brews outside, a jovial dance sequence is underscored by the howling of an ominous wind, Elena is transformed into a demonic and opera-singing sexual predator, and Snàporaz slides down a brightly-lit rollercoaster of female-themed memories, one that ultimately plunges him into dark isolation and places him on trial for his crimes against womankind. It's as wildly imaginative and visually astonishing a final act as you'll find anywhere in Fellini's oeuvre, crammed to the gills with extraordinary ideas and imagery and infused with a penetrating sense of personal doom, reflecting the director's original desire to make a film about death.

All of which may make City of Women sound like a bitter portrait of women as vindictive castrating bitches, which it most definitely is not. This is Fellini attempting to reconcile his long-held love of women with the reality of changing times, using the camera as his psychiatrist and Father Confessor. There's little real hostility here, only the apprehension of a man who feels out of his time, one intimidated by youth and the politics of feminism but equally uncomfortable with the machismo posturing of the Katzones of the world, who still exist to this day. And the film has exuberance and style to spare, in the inventiveness and wit of its storytelling, in Giuseppe Rotunno's seductively fluid camerawork, and in the eye-popping vision of Dante Ferretti's production design. Fascinating for its place in the oeuvre of a man with a long-standing cinematic fascination for women, its a hugely imaginative and entertaining ride and unquestionably the work of a great and talented artist, but one whose uneasiness at the notion of female empowerment can't help but feel like a last gasp of insecure chauvinism in an age of progressive enlightenment.

The restoration here undertaken by Gaumont in France (who also produced several of the extra features) is largely excellent, albeit with one small caveat I'll get to in a second. Sharp and detailed without resort to any obvious digital enhancements, the contrast is nicely balanced and generous in the range of visible detail. The colour palette has the sort of warm earthy bias common to some film stocks of the period, but when brighter colours appear they are richly reproduced – check out the vibrant glow of Katzone's jukebox if you're looking for an example. What does surprise a little is the quite pronounced digital banding that briefly appears on the backlit fog when Snàporaz is menaced by the teenagers at night, which is particularly evident on the image of an approaching airplane and the shots that surround it. Fog has always proved a serious challenge for digital transfers, but the higher bitrate and resolution offered by Blu-ray should, in theory, make this a thing of the past. It doesn't last long (though is foreshadowed by a less obvious but still visible occurrence on the train toilet door), and I did wonder at one point if it was an issue with my TV, but it's also visible on other screens and players I've tried and on screen grabs of that scene. On the whole, though, this is as good as I've seen the film look, and by a sizeable margin, easily justifying its Blu-ray incarnation.

The PCM 48 linear mono soundtrack has the expected range restrictions when compared to a modern digital surround track but is still clear and free of damage, and while the (post-dubbed) dialogue can feel a little harsh when the volume rises, the music always plays well and without a hint of distortion.

A Dream of a City of Women (30:25)

A retrospective documentary by critic and filmmaker Dominique Maillet featuring newly shot interviews with City of Women producer Renzo Rossellini, film historian and Fellini's friend Aldo Tassone, critic and filmmaker Carlo Lizzani, and director and Fellini's former assistant Dominique Delouche. Although constructed almost entirely of talking heads (there is some brief on-set footage cribbed from the documentary below), this proves consistently interesting stuff, outlining how the film came into being and revealing quite bit about Fellini himself, his response to the rise of feminism, his cinematic intentions, and his relationship with favourite actor Marcello Mastroianni. Particularly intriguing, at least for this newcomer to the story, was the news that actor Ettore Manni was a lot closer to the character of Xavier Katzone than I would ever have realised, and that – in what has to take some sort of prize for horrible irony – he died during the production when he shot off his penis. The jury's still out on whether it was an accident or suicide; Rossellini clearly had little time for the man and suggests that he died of stupidity.

Notes on City of Women (60:18)

Made in 1980 in tandem with the film itself, this is an elegantly shot and assembled behind-the-scenes documentary, with extensive footage of the filming of key scenes peppered with brief interviews with cast and crew members. The best of these is a walk-and-talk with Mastroianni, who at one point pauses to call out to a camera-mounted Fellini for advice on what to say, and whose ending is so perfectly timed that you can't help wondering if this was more rehearsed than it looks. The scale of production really comes across in the construction and size of the sets and the operational mechanics, particularly the exterior rollercoaster and the all-hands-on-deck train-journey fakery. The footage of Fellini directing is terrific stuff, though in what may be the most telling moment of all, some of the women recruited as extras worry that the film will not accurately reflect the progressive nature of feminism and suggest that to do so would really require a female director. Most behind-the-scenes documentaries you find on DVDs can only dream of being even half as good as this.

Dante Ferretti: A Builder of Dreams (21:20)

An interview with top production designer Dante Ferretti (whose impressive list of credits include Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, The Name of the Rose, The Age of Innocence, Casino, Gangs of New York and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street), who recalls working with Fellini, his own work on this film, and why he turned down the director's first request to work with him – "Call me in ten years," he told him, "I'll have more experience and you'll be fed up with everyone else."

Tinto Brass (11:07)

An interview with Fellini's friend and fellow filmmaker Tinto Brass, whose main focus of discussion is Fellini's love of women and how it manifests itself in his cinema. There are a couple of dodgy stories – Brass recalls an actress with whom he had a relationship solely by the size and shape of her breasts – but he also offers some interesting insights, suggesting that Fellini saw aspects of himself in his female characters and that presence of women in his films is more important than the story.

Italian Trailer (3:37)

A curious trailer constructed from stills and footage of Fellini directing; it almost plays more as a trailer for Notes of City on Women above.

French Trailer (1:27)

More recognisable as a trailer for the film itself than the above, this French trailer pre-empts the now common practice on UK and US trailers for foreign language films by not including any dialogue, presumably in the hope that subtitle-phobic audience members will not realise it's Italian.

Booklet

Rounding things off is the excellent-as-ever MoC booklet, which includes three revealing interviews with Fellini about the film, an on-set conversation with Marcello Mastroianni by Maurizio Porro, two recalled dreams by Fellini (the illustration of one is used for the booklet cover), credits for the film, notes on correct viewing and some high quality stills.

Even as I was writing the last line of the above review I was acutely aware of both the progress made in the still-ongoing fight for gender equality and how far there still is to go. Women continue to be abused and oppressed by men and objectified as sex objects on the pages of tawdry newspapers, and the rise of lad culture in the UK has seen the sort of idiot chauvinism that has created barriers for true female empowerment for centuries come depressingly back into fashion. In this context, City of Women's nervous response to the rise of female assertiveness comes over more as quaintly old-fashioned than reactionary, and while it may not be one of Fellini's very best, it's so imaginative in its ideas and execution that it's hard not to love it just a bit. The Masters of Cinema Blu-ray is a particularly good one, even by their usual high standards, the impressive transfer backed up by an excellent collection of first-class extra features. Warmly recommended.

|