|

The 1989 Australian drama Celia opens with an impactful incident that is presented so matter-of-factly and so soon after the film begins that its full implications do not immediately register. 9-year-old Celia Carmichael (an excellent Rebecca Smart) enters her grandmother’s room one morning to wake her and discovers that she has died in the night. The film then cuts immediately to the grandmother’s funeral, where Celia leans into the open coffin and whispers a parting message, “Take care Granny. I’ll miss you.” At this point, we know little about Celia or her relationship with her grandmother, but when she is woken that night by an alarming noise outside and the sight of a monstrous hand reaching through her bedroom window, her immediate reaction is to call out for her departed relative. Instead of just trying to reassure her and convince her that it was a dream, her sensible mother Pat (Mary-Anne Fahey) takes her into the garden and uses a torch to reveal that a possum was likely the source of the noise. Seconds later, however, Celia spots something more humanoid in shape scuttling away through the bushes.

We clued in to the identity of this creature when Celia and her classmates are at school the next day, listening to their teacher reading aloud from The Hobyahs, the sort of children’s story that would probably give its readers nightmares (a trait common to the original texts of many fairy tales). As the teacher reads, we’re treated to a wonderfully creepy visual interpretation of her words, a mix of book illustrations and live-action footage that provide us with a clear look at the creatures of the story’s title. No question, it was a Hobyah that was reaching into Celia’s room the previous evening. At this point in the story and we’re only six minutes into film that runs for 102 minutes – it’s easy to see why the film is sometimes misleadingly labelled as horror (in America, it was tackily and deceptively retitled Celia: Child of Terror), but even at this early stage it seems obvious that the Hobyah that visits Celia by night is no more than a waking nightmare fuelled by the repeated reading of a favourite story. She’s also having visions of her late grandmother, whose appearances and immediate vanishings also have the unmistakable ring of a mirage. Go into this film, particularly with that American title in mind, expecting Celia to be a demon child with supernatural or demonic powers and you’ll find yourself in very different territory.

The first sign that this is not a work of fantasy-driven horror comes early with a caption that specifies the temporal setting as December 1957. There are usually only three reasons for such a specific period setting: that the story is based on a factual incident; that aspects of it are relevant to world, national or even local events of that time; or that the tale is autobiographical in nature. Only rarely do these real-world specifications apply to a fantasy-based genre such as horror (Guillermo del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth are prime examples of films where they do). Celia falls into the second camp, and quickly evolves into a reality-grounded drama that kick-starts when Celia arrives home from school to discover a new family in the process of moving in next door. As they carry their possessions into the house, Celia catches the eye of friendly mother Alice Tanner (Victoria Longley) before her attention is drawn to boxes full of books waiting to be unloaded. It’s a simple shot that told me more about Celia (and, as it turned out, her bond to her grandmother) than anything she’d hitherto said. This is exactly the sort of low-key but thoughtful filmmaking that pulls me into a story like the one unfolding here.

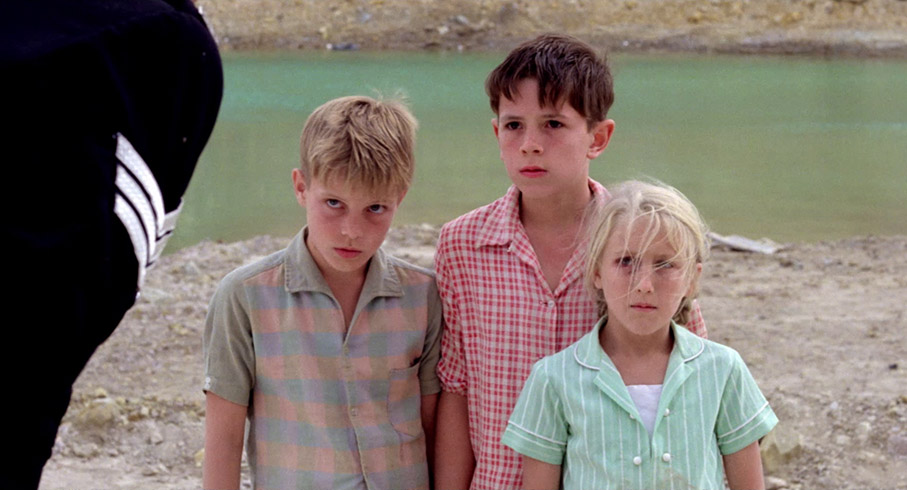

As an only child, Celia is immediately drawn to the Tanners and becomes firm friends with the family’s three children, Steve, Karl and Meryl (Alexander Hutchinson, Adrian Mitchell and Callie Gray). Alice fully engages with her kids in a way that that is almost alien to Celia, and while she also becomes friendly with Pat, she is quickly eyed-up by Celia’s father, Ray (Nicholas Eadie), who clearly fancies his chances with this attractive new neighbour. Celia and the Tanner children soon find themselves in conflict with a gang of kids led by Stephanie (Amelia Frid), the bossily smug daughter of Ray’s closest friend, John Burke (William Zappa),* who also happens to be the local police Inspector. Their playground and occasional battleground is a deserted a local quarry, in which sits a small metal shack that Celia has made into den. If the post-funeral hallucinations she experiences there are any indication, it’s also a place where she once spent happy times with her grandmother.

None of this, however, is specific to the time and place in which the film is set. What does become relevant is Celia’s long-held desire for a pet rabbit at a time when the Australian countryside was overrun with the animals, and the government had embarked on a program of mass extermination. It’s a pet that her rival Stephanie owns and taunts her over, but something that Celia’s father repeatedly refuses to buy for her because he regards them as vermin. This, it turns out, has its human equivalent, as Alice and her husband Evan (Martin Sharman) are active members of the Communist party at a time of growing anti-communist hysteria. We soon learn that Ray is as hostile to communists as he is to rabbits, and when he learns about Alice and Evan’s political convictions, he forbids Celia to ever associate with them again. This clearly drags up bad memories for Ray, first hinted at when Celia takes refuge in her grandmother’s former bedroom, a corner of the house she has been forbidden from entering and in which books on Marxism and Lenin line the shelves, books Ray later angrily and symbolically burns to the protesting Celia’s despair. Aware that his daughter will likely defy him, Ray then tries to dissuade her from seeing the Tanners by buying her the rabbit she has been so long clamouring for. It’s the moment at in which the film’s political subtext almost becomes the main narrative, as Ray effectively tries to bribe his daughter with what he regards as the lesser of two evils, both of which Alice is drawn to, and both of which her father would like to see wiped from the land.

Celia is a film that functions simultaneously on several levels, developing from its horror-tinged opening into a coming-of-age drama, a history lesson, and an allegory on governmental manipulation and how prejudice is shaped by propaganda, and on that score the UK release of this Blu-ray couldn’t be more timely. As our own deeply corrupt and incompetent government, aided by its loyal media outlets, attempts to turn public opinion against our former allies and see them as the enemy in order to distract from its own monumental failings, many still refuse to accept an alternative narrative because they have bought into the lie and are now too invested in their original decision to reverse course. Ray is attracted to Alice and clearly regards her as a good person, at least until he learns of her political beliefs, which in his mind somehow transforms her into something that he has been propagandised into believing is inherently evil. In such a situation, civilised debate becomes impossible, as disagreements degenerate into off-the-peg sloganeering rhetoric, and whatever argument Alice might attempt to put forward, her words are always doomed to fall on deaf ears. Sound familiar?

Of course, none of this would hit home if the surface drama did not fully engage, but on this level Celia also really delivers. The film may be set before I was born, but the picture it paints of a pre-internet and pre-social protection childhood is one that transported me back to my own younger days. Just like Celia, my friends and I had our improvised playgrounds on little-used public land a safe distance from home base, while similar rivalries between young gangs that could also escalate into missile-throwing battles. In the film, this conflict is escalated by the anti-communist chants of Stephanie’s gang, a ready-made and government-endorsed prejudice that in my youth could take on any form that those looking to stoke division could dream up. The film also really touched a nerve with me in what it reveals about Celia’s relationship with her grandmother. I’m not going to claim that I was as close to mine as Celia was once to hers – we never shared a house and even lived several miles from each other – but I got the clear impression that while my rather conservative father and uncle both loved my grandmother dearly, they were never really comfortable with her committed socialist beliefs. I, on the other hand, increasingly found myself more in tune with her politics than those of my parents, and given that she was also an avid reader and a devoted film fan, the two of us developed a special bond that I dearly missed when she passed away.

Despite what I said earlier, it is worth noting that the film’s (re-) classification as horror – which I still think is misleading – comes from more than just Celia’s early dark fantasies, and while I’m not going to get into the specifics of what happens to darken the tone, I will admit that the first time I watched the film, it send a cold shudder through me that stayed until the closing credits, and beyond. It’s something that newcomers should not be aware of in advance, and with that in mind, I’d avoid the film’s IMDb page, which features a poster that acts as a partial spoiler, and which made me wonder what fuckwit decided that this was an appropriate image with which to advertise this film. There are certainly dark moments that act as pointers to this late-story turn of events, particularly in Celia's definatly rebellious nature and the ritualistic pinning and burning of effigies of enemies, but for me this still rang true, awakening distant memories of an time in my life when I had yet to develop a clear moral code or even consider the true consequence of my actions. Maybe it’s just me. Well, not just me…

Celia is one of those rare debut features that is so thoughtfully structured, so impressively acted – there’s not a wrong note in any of the performances here – and so confidently directed (the politics that connect Celia’s grandmother to the Tanners is a beautifully handled reveal) that it becomes, a little unfairly, a yardstick by which the filmmaker’s subsequent work becomes judged. Whether this has been the case for then first-time writer-director Ann Turner I’m not currently in a position to say. I came unforgivably late to Celia, and despite the high regard in which it is held, I was still left with the feeling that I’d stumbled across a little-seen and previously undiscovered work of the New Australian Cinema of the late 1970s and early 80s. It’s a captivating and ultimately haunting film, one in whose spot-on depiction of the adventures and traumas of childhood is underscored by a still-pertinent allegorical subtext, before a discomforting move into considerably darker psychological territory. It’s a film that never shouts because it never needs to, but which still managed to leave me quietly reeling, and itching to watch it again. Remarkable.

A lovely, rich 1080p transfer in the film’s original 1.85:1 aspect ratio. Detail is sharp and clearly defined without a whiff of edge enhancement, and the handsomely rendered colour has a warm, pastel feel whilst keeping the flesh tones naturalistic and nailing the black levels, all of which contributes to the film’s unforced period feel and the look of a work made during the New Australian Cinema heyday. In the daylight exteriors in particular, the contrast, light levels and colour are all absolutely spot-on, and the National Film Archive of Australia restoration has cleaned the transfer of dust and damage. A fine film grain is visible throughout.

The Linear PCM 2.0 dual mono track is consistently clear and with a decent dynamic range, not that this is a film that makes use of punchy bass notes. Again, the transfer is clean of any wear or damage.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Celia’s World (61:22)

An unexpected but hugely welcome and informative documentary, directed by Ann Turner in May and June of this year in Melbourne during the Covid lockdown, and constructed almost entirely from video conference interviews with primarily female academics, many of whose parents were members of the Communist Party during the period in which the film was set. They include Ann Curthoys, whose book Better Dead Than Red: Australia's First Cold War was a huge influence on Turner when she was writing Celia, and Annette Blonski, who acted as script consultant on the film and was the child of Polish Jews who emigrated to Australia. Through this, Turner explores in considerable detail the experience of growing up in Australia as a child of committed left-wing political activists during a time of anti-communist rhetoric, why many became disillusioned with the party after Khrushchev’s Secret Speech and the suppression of Hungarian Uprising, and how their political beliefs sometimes triggered a prejudicial response. Memories of owning a pet rabbit when the law was passed banning them are shared, as are those of being able to play freely wherever you pleased and the sometimes violent behaviour of young gangs. Dr. Mary Tomsic, Research Fellow at Australian Catholic University, champions Celia as a feminist work and examines how sits in the recent cycle of women-directed horror films. I was utterly fascinated by this extra, and despite being just over an hour in length, it never feels repetitive or remotely superficial.

Interview with Ann Turner (14:16)

Shot on analogue video for Second Run’s 2009 DVD release of Celia, this interview with writer-director Ann Turner is an excellent first port of call once you’ve watched the film itself. She recalls how she got into film school and the range of world cinema titles it opened her up to, the inspiration for Celia and how the film functions as a metaphor for governmental behaviour, the casting of Rebecca Smart in the title role, the influence of growing up in 1960s Adelaide, and more. Turner is a most personable interviewee, and this proves an enjoyable and educational watch.

There’s Something About Celia (17:33)

A recording made after a screening of Celia at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne on 11 April 2021, in which Maria Lewis talks to film critic and writer Alexandra Heller-Nichols about the film, which is captured in a single wide shot whose framing is doubtless enforced by the participants’ social distancing. Heller-Nichols reveals that her first viewing of Celia really messed her up, but also that it has since become a favourite film that she watches regularly. She praises the performances of the adult female leads and the relationship between the two mothers, talks about director Ann Turner’s early short film, Flesh on Glass, and notes that many of the best horror films draw from real life and blend fact with fiction.

Image Gallery (2:00)

120 screens (including title slides) of production stills and behind-the-scenes photos, many of which are of very high quality.

Booklet

There are three key inclusions here, all of which are essential reading. First up is an excellent essay on the film by freelance writer and multimedia producer Michael Brooke, who offers an insightful analysis of the film and its release, and contextualises it in terms of the female-dominated Antipodean New Wave. I was particularly pleased to see Alison McLean’s extraordinary but rarely seen short film Kitchen Sink getting a mention here. Celia is examined from a more socio-political angle by Joy Damousi, Professor of History at the Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences at the Australian Catholic University, in an essay that includes some discussion on the Celia’s World documentary detailed above. Finally, there is a most welcome reproduction of the story that inspires Celia’s nightmare fantasies, The Hobyahs, which is prefaced by some background on its origins and appropriately sub-titled A traditional tale to keep children awake at night. No kidding. It’s an excellent booklet, but one that should not be read or even opened before watching the film – the centre-page photo could count as a major spoiler.

I can offer no excuse for why it’s taken me so long to see a film so tuned to my tastes, sensibilities and memories as Celia, and even though I was sent a review disc by Second Run, the release date had come and gone before found the required time to sit down and watch it. I’m so glad I did. As an unsentimental tale of the struggles of childhood, it’s up there with the best, and its socio-political subtext has found new relevance in a world that is increasingly divided by cultish and government-led ideologies. There’s not a single sequence in this film that could not be expanded into a layered analytical essay if you were so inclined, yet it still grips as both a character study and social history lesson, and can be watched and enjoyed for the performances alone. A terrific film on an excellent Blu-ray. Highly recommended.

|