|

As a viewer and especially as a reviewer, I always get a kick out of watching film operate on more than one level simultaneously, when it's enjoyable and engaging on the surface but also offers up a clear subtextual reading. In the past, I've made the argument that we as film analysts sometimes see implied meaning where none was intended, but there's also a case to be made for deconstructing elements that the filmmakers themselves were not conscious of at the time, reflections of their own fears, beliefs and influences that only become evident when viewed in the context of their whole body of work. Try doing a search for the Catholic undercurrents of Hitchcock movies and see how many hits you get. But in Czech New Wave cinema of the 1960s, you can bet your bottom dollar that much of the subtext was fully intended, smuggled messages designed from the outset to comment on the society of the day and a government that had the power to restrict artistic freedom and bury the work of some of cinema's most imaginative creators.

With that in mind, consider this early sequence from director Vojtěch Jasný, The Cassandra Cat (Az prijde kocour, also known as When the Cat Comes). It features two characters with very different world views who work for the same school in a small but architecturally beautiful Czech town, schoolteacher Robert (Vlastimil Brodský) and headmaster Karel (Jiří Sovák). Both men are captivated by the sight of two storks circling majestically over the town, but as Robert edges slowly forward whilst filming them with a handheld movie camera, Karen approaches at a similar speed from the opposite direction whilst taking aim at one of them with a shotgun. It instantly occurred to me (and to the contributors to the commentary track on this disc) that both men were defined by how they are choosing to shoot the birds, Karel with a weapon that will rob the targeted animal of its life, and Robert with a device that will preserve its grace and elegance without harming it or disrupting its life in any way. Only later did it occur to me that this dual meaning for the word 'shoot' might be specific to the English language, which could make this a happy accident for us as English-speaking viewers rather than an intended reading.

Right here and in the scene that immediately follows, the personalities of two characters that we've only just met and the beliefs that separate them are effectively defined. Karel is clearly representative of the ruling authority, an essentially corrupt man who professes to believe in the rule of law and whose abuse of authority extends to taking advantage of his compliant secretary, Julinka (Jirina Bohdalová), who also happens to be the unaware Robert's girlfriend. Robert, on the other hand, is a progressive humanitarian who sees all animal life as precious and keeps a variety of pets that he uses to educate the cheerfully inquisitive young children in his charge. Where Robert seeks to fire his students' creativity, Karel dismisses the whole concept of imagination as a unscientific in a brief conversation with Robert that slyly comments on the notion of the censorious state versus the creative artist. "There's only one path," Karel tells Robert, "just as there's only one truth, right?" to which Robert responds, "Especially if it's your truth," a response that clearly rankles Karel. If the allegorical aspect of this disagreement hadn't already landed, Karel then chastises Robert for walking on the red line of tiles the runs down the centre of the school's main corridor (that he does so like a tightrope walker also has later relevance), barking out correctively, "To the right, please, comrade teacher!"

Even before this scene begins, we've been introduced to a whole slew of characters, several of whom will figure prominently later. Delivering this economic overview of his town is castellan Oliva (Jan Werich), who starts his day by observing the citizens from his clocktower balcony home through an improvised telescope, passing comments on each of them and their activities for us as he does so. It's he who slyly establishes the tone of the film to follow in his opening address, which is delivered to camera through a maintenance hatch on the clocktower face. "Once upon a time…" he teases, then assuring us, "This really happened," a collision of two opposing storytelling proclamations that suggests a factually-based fairy tale. At the film's conclusion, he will modify this statement in a way that also invites an inescapably political reading.

It's Oliva who lays the ground for a turn of events that is set to have a hugely disruptive impact on all of the townsfolk when he is invited by Robert to sit as a model to be drawn by his pupils, all of whom would far rather hear one of Oliva's stories. The tale he spins is a fanciful one, of falling in love with a woman named Diana who worked in a traveling carnival, and who owned a cat whose gaze would turn audience members a colour that revealed their true nature and deeds – violet for liars and hypocrites, yellow for the unfaithful, red for the love-struck, and grey for pilferers and thieves. To prevent the animal from exposing the true nature of those who attended their shows, the cat wore sunglasses to shield its revealing gaze, but at one show, the curious young Oliva could not resist removing them, and the results proved true to Diana's claims. Not wishing others to know of this darker side of their personalities, the violet and grey people killed the cat, and Diana subsequently disappeared.

As Olivia tells his tale, and then joins Robert for a song, the class is secretly observed by the school's bootlicking Janitor (a nicely judged comical turn from Vladimír Menšík), and by the time he has called on Karel to witness what is unfolding, Oliva is dancing an energetic jig, spurred on by Robert and delighting the children. Karel hauls Robert out of the class to chastise him for inviting a man he regards as a vagrant into his school, and especially for the crime of encouraging imaginative thought. Before this discussion can evolve into full-blown conflict, it is interrupted by the arrival in town of a small carnival lead by a Magician who is the exact double of Oliva (also played by Jan Werich), next to whom is a beautiful, red-dressed woman named Diana (Emília Vášáryová) whom Robert is instantly besotted by, and who holds in her arms a cat whose eyes are shielded by sunglasses…

It's at this point that what starts as a tonally light-hearted drama with socio-political undertones makes its first moves into the realms of the fairy tale suggested by Oliva's "Once upon a time…" introduction. Following the locked-eyes and blown-kiss connection they make on the carnival's arrival, Robert and Diana then meet in a manner that is emblematic of the film's economic way with film storytelling, as well as providing the first signs of the delightfully offbeat direction in which it is soon to head. As Robert searches for his pet cat after it chased the sunglasses-wearing moggy Mourek (the attraction that these animals seem to have for each other being a reflection of the spark that has ignited between their owners), he is hit smartly on the head by the opening door of the carnival van. The blow spins him 180 degrees and points his eyes directly at the fountain on which his cat and Mourek are happily relaxing, and as he turns back he is greeted by the cheerily bewitching smile of Diana, who treats his injury – and I have to presume this was once a real thing – by pressing a cold clothing iron against his head. Emília Vášáryová really is fabulous casting here, her captivating beauty and radiant smile making it oh-so easy to see her exactly as Robert does and be similarly enchanted by her. That her clothing and the paintwork on the vehicle in which she arrives into town are bright red is also significant given the meaning assigned to the colour by Oliva's story.

Even before the arrival of the carnival players, director Jasný plays games with film form and edges the drama into the realm of magical realism when Karel's secretive and lascivious fondling of Julinka is interrupted so that his wife Ruža (Stella Zázvorková) and the Janitor can present him with the stuffed body of the recently shot stork. Wanting then to see a simulation of the flight of a bird that he prevented from ever flying again (oh, the irony), Karel has the Janitor run around the room holding the majestically posed animal aloft. As he does so, a raucous orchestral polka bursts onto the soundtrack, one that everyone in the scene seems able to hear and claps cheerfully along to. As the two women beam wide smiles at the Janitor and bob merrily and even alluringly to the music and Karel claps out a more restrained but encouraging rhythm, the janitor runs in increasingly dizzying circles around them. As he does so, his expression constantly shifts in amusing and slyly telling fashion, as initial elation gives way to briefly dour looks thrown at the headmaster, which switch on a beat to expressions of cheerful appreciation at the reaction his actions are prompting from the women, and increasing signs that the constant motion is starting to induce a degree of nausea. The vibrancy of the action and the music is matched by Jasný's direction and Jaroslav Kučera's scope cinematography, which switches back and forth between energetic pans of the Janitor as he runs around the room with the bird and his viewpoint of the others as he rapidly circles them.

More playfully experimental is the classroom scene in which Robert encourages his pupils to write or draw something they like or dislike about their town, and the thoughts of the students are visualised on the blank sheets of paper before them as flickering monochrome film clips from their lives. These give way to vocalised thoughts that tell their own small stories, as one child muses, "They teach us in school that the most beautiful things in the world are friendship and honesty, but some people never tell the truth…" and another ponders more soberingly, "I don't like my daddy but I won't write that down because he'll beat me." It's when Oliva starts telling the tale of Diana and the magical feline that the children really become inspired, which is captured in an entrancing montage of shots of the kids painting pictures that illustrate his story. So enchanted was I by this sequence that – for the first time in living memory – I had to stop and rewind the film to read subtitles I had found myself all but ignoring as a result. And oh, the emerging talent of some of these kids – just look what you get when imagination is fed and allowed to run free.

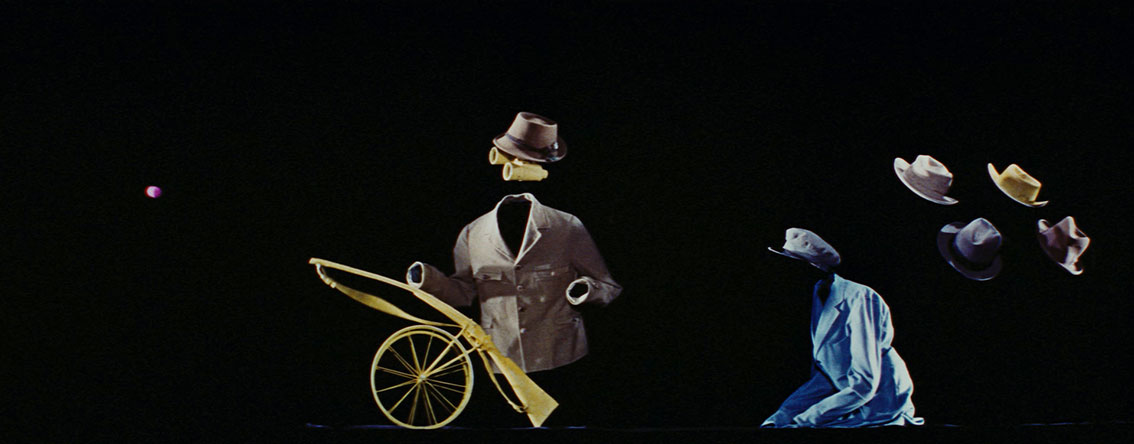

It's when the whole town attends a magic show put on by the visiting performers that reality takes a gloriously inventive and visually thrilling hike. As the velvet-clad supporting players move invisibly in the shadows on a carefully lit stage, manipulating objects to make them appear as if they are moving of their own accord, key personalities of the town and their earlier actions are symbolically recreated in what fells almost as a fanciful take on the play-within-a-play sequence from Hamlet. This already captivating illusion is further enhanced by some cinematic trickery borrowed from silent era photographic effects pioneer Georges Méliès, and moves into jaw-dropping overdrive when Diana removes Mourek's sunglasses and the cat's gaze has the same effect on the townspeople outlined by Oliva in his story. In a flash, the citizens are visually transformed and begin congregating in colour-coded groups, panicking, dancing and confronting each other in a scene that takes the essence of the Dance at the Gym sequence from West Side Story and runs with it in an exhilarating explosion of movement, energy, surrealism and vibrant colour, and Jan Chaloupek's previously deft editing moves into turbo-charged overdrive.

In the fallout from the dance, Oliva finally meets his doppelganger and nudges the fourth wall by asking him, "What is this, a symposium of doubles? Or is it a collision of matter and antimatter?" while Robert and Diana go on a date that is rife with relationship symbolism. After dancing in the countryside whilst glowing red with love, they row to an island where they sit at a pre-prepared table, and chess game-like movements of wine glasses become the visual equivalent of those tentative questions you ask each other when mutual attraction brings you together for the first time. Elsewhere, metaphor and political allegory are moved slyly to the fore, as Mourek is regarded as a disruptive revolutionary by town elders that its gaze of truth has exposed as corrupt, and they meet in secret to plot its assassination. They also attempt to scapegoat Robert in an effort to quash his influence on the children, whose purity of vision and collective strength cast them as progressive revolutionaries, a role they eventually play to the hilt, holding the town to ransom in order to secure their demands.

There is so, so much more I could talk about in this extraordinary film, but there comes a point where I have to just sign off and urge you to see if for yourselves. Although also enthusiastic fans, the contributors to the commentary on this disc seem to favour Jasný's 1969 Cannes award winner All My Good Countrymen [Všichni dobří rodáci], which I admit to not having seen (yet – I'm now really keen to do so), so I'm not in a position to make such comparisons. I went into this film knowing little about it and was quickly swept up by it, the smile that spread across my face intermittently widening to Cheshire Cat proportions but never fading for a second. It's a hugely and joyously inventive work that intermittently explodes with energy and imagination, its every scene underscored with social and political allegory that always hits home but is never blunt enough to metaphorically smack you around the face. Indeed, I needed a second viewing to start unpicking some of the more subtle symbolism, and have only touched on the many layers that you'll find in the scenes that I have chosen to discuss. I'm sure others will be more critical and good luck to them, but I loved every multi-layered scene, every performance, every carefully composed shot and smart edit of this remarkable, savvily political and ultimately life-affirming salute to the power and importance of imagination and free thought.

The 1080p transfer on Second Run's Blu-ray, which is framed in the film's original aspect ratio of 2.55:1, was sourced from a new 4K restoration by the Czech National Film Archive, one whose strongest aspect is, intriguingly, not immediately apparent. The image is very stable and largely clean of dust and any former damage, and although not exactly reference quality, the sharpness and clarity of the detail are very good and pleasingly consistent. The colour palette has an earthy tone to it that I initially put down to the age of the film and the stock used, yet come the centrepiece magic show scene, I was given cause to suspect this was a deliberate decision. I then wondered if the drab colour palette was used specifically to capture the mundanity of everyday life in the town, as the show itself is littered with bright colours and moves onto another level when Diana removes Mourek's glasses and the townspeople display their true personalities. Here, the colour absolutely sings with a vibrancy and intensity that you can almost taste, which is all the more astonishing when you consider that the effect was achieved not using visual effects but through costume and make-up colouring.

And then we have the soundtrack. Few who know their Czech New Wave cinema would be surprised if this early entry in the movement had a mono soundtrack, and that's certainly what I was expecting. I was thus genuinely startled to be presented with a DTS-HD 5.1 Master Audio surround track instead, one that may not have the tonal range of a more modern work, but that still really impresses in its clarity its muti-channel separation of dialogue, ambient effects and music. This has clearly also been restored and those responsible have done a very fine job.

The English subtitles that kick in by default can be switched off on the fly or on the main menu if your Czech is up to the job.

Projection Booth Audio Commentary

This variation on the usual audio commentary formula has Mike White, Spencer Parsons and Chris Stachiw discussing the film, not as they watch it but a while after after having done so for an episode of The Projection Booth podcast. The fact that it runs for the exact length of the film suggests either a happy coincidence, a deliberately set episode time limit, or some judicious editing. I also have a suspicion that some or all of the men were in different locations when this was recorded, hence the early boisterous nature of Chris Stachiw's contribution – it's almost like he wasn't sure his mic was working properly. It matters little, as all three individuals here really know and love their movies and what they've seen of Czech New Wave cinema, something that White is clearly the main authority on – he has the others jumping in excitement when he tells them of Jindrich Polák's 1977 Tomorrow I'll Wake Up and Scald Myself with Tea [Zítra vstanu a opařím se čajem] (also avialable on Second Run Blu-ray), a film they've previously never heard of and instantly want to see. There's a lot of ground covered here, including the lead actors, the smuggling of critiques of the government into a live action fairy tale, the nature of truth and perspective, why taking a while to get the plot going ultimately proves rewarding, the telling use of close-ups, the technical wizardry, and plenty more. Comparisons are made with director Jasný's later All My Good Countrymen, which as I noted above they appear to hold in even higher regard, and connections are drawn to several other notable works, from Rear Window to Mulholland Drive. There also a really interesting discussion about the ending, which for obvious reasons I'm chosen not to touch on above. Well worth a listen.

Badly Painted Hen [Špatně namalovaná slepice] (13:38)

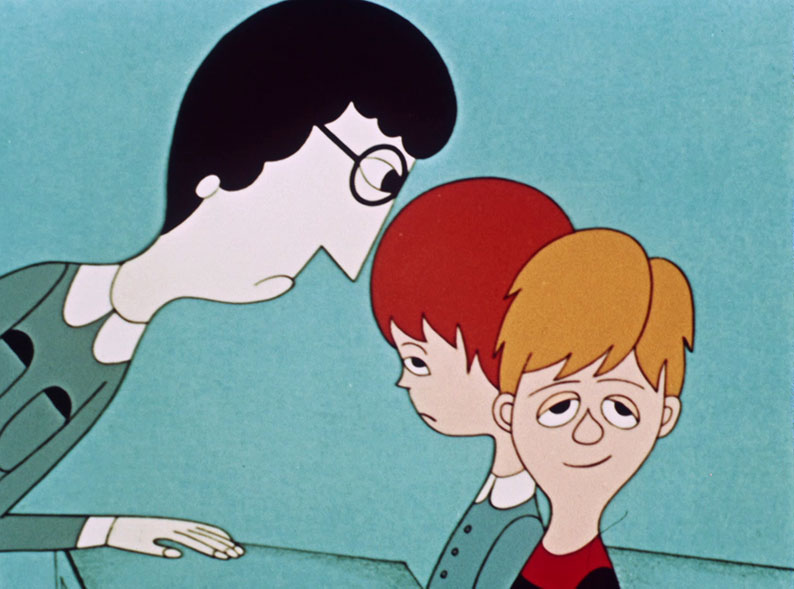

This delightful animated short (which I've also seen listed as the slightly more officious Incorrectly Drawn Hen) was written and directed by The Cassandra Cat co-writer Jiří Brdečka, and shares several of that film's socio-political undercurrents. At school one day, an overly fastidious schoolteacher chastises one boy for dreamily looking through the window and mentally repainting the industrial landscape outside instead of paying attention to her stern teachings. She then sets the class a project to copy a meticulously scribed lithograph of a hen that she displays on the wall, inviting each child to make their own interpretaion. The class swot, who looks like a young Jacob Rees-Mogg and is every bit as insufferable, recreates every line of provided example with technical drawing accuracy and is praised by the teacher as an example for the rest of the children to follow. Perish the thought. As she works her way through the other completed pictures, she comes across the one created by the daydreaming boy and is horrified by its inept crudity. It ends the day torn up and tossed in the bin, but that evening comes to life and flies into town, where a chance encounter sees its status unexpectedly elevated.

The central theme here is evident from the moment the prim and proper teacher chastises the young boy for using his imagination instead of toeing the line that she sets with her mathematically accurate placement of objects on her desk (at one point her gaze wittily measures the distance both ends of a pencil are from the desk's edge). As with Robert in The Cassandra Cat, this is all about the creative artist verses the restricyions of a censorial ruling authority, and the film absolutely comes down on the side of the former. For a start, the daydreaming boy's drawing may be crude and nowhere near as technically accurate as Rees-Mogg Junior's, but as a minimalist interpretation it's pretty damned good. This can't help but cast the boy as representative of those game-changing art movements of the late 19th and early 20th century – as well as film movements of the 1950s and 60s, Czech New Wave included – that kicked against and upset the established norm, but ultimately broadened the scope of art in general and sent it in exciting and rewarding new directions. As with those movements, the boy's vision is later validated, though he is still denied recognition by the establishment representative, none of which seems to bother him in the slightest. A political statement this may be, but it's emchantingly and inventively handled, with most communication visually represented (as an example, affection is expressed by the simple stroking of the hair of another), and occasional brief spells of vocal interaction are delivered as comically voiced gibberish. And as a parting statement of intent, I can't be the only one who beamed a wide smile when the boy's newest artistic creation takes an aerial crap on the young Rees-Mogg's head.

Theatrical Trailer (1:36)

A dialogue-free 2021 re-release trailer whose first half consists of shots from the schoolroom painting sequence, while the second half boats tantalising snippets from the magic show.

Booklet

The accompanying booklet contains only one essay but it's an absolute belter, a richly detailed, informative, and hugely engaging look at the film, director Jasný, the bumpy journey the film undertook from conception to eventual production, its release, and its influence. The main credits for the film are also included.

If the claims of the enthusiastic trio on the commentary are correct, I may be at a slight disadvantage viewing The Cassandra Cat without having also having seen the director's later and more widely acclaimed All My Good Countrymen. Then again, maybe not, as I was able to approach the film without any expectations shaped by Jasný's other work, which doubtless contributed to the positive impression it made on me. I loved this movie, for its energy, for its invention, and for the sheer density of its subtext, which is both playful and political without ever coming across as didactic. A terrific film with a handsome transfer, a busy and informative commentary, an excellent booklet essay, and a short film that's almost worth buying this disc for alone. Highly recommended.

|