"Give the public Mars, and public support for the space programme will fly like a rocket." |

Stuart Atkinson – New Mars, 7th March 2003 |

I have a close friend who is a bit of a conspiracy theorist. Actually, theorist is pushing it a bit. It's not a subject she's made a study of; she just believes that certain events are the result of sinister machinations. She is utterly convinced, for example, that Diana Spencer was murdered on the orders of the Queen, and completely stonewalls any attempt at debate on the subject. She's also never believed that anyone ever landed on the Moon and that the whole thing was faked in a film studio.* She remains stubbornly deaf to any talk of the retroreflectors placed there by the Apollo astronauts that anyone with a powerful enough laser can use to measure the precise distance between the Earth and the Moon. Then again, she probably has her suspicions about lasers as well, or at least those who own or operate them. I was thus not in the least surprised to learn that she is not only a big fan of the 1977 thriller Capricorn One, but to this day regards it as something of a factual record.

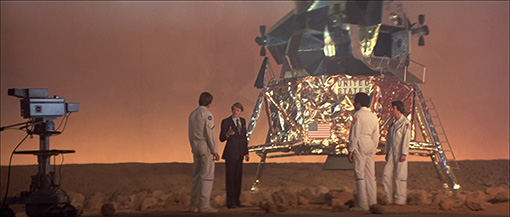

If you're new to the film then some clarification is probably in order. The three astronauts of the first manned mission to Mars – Colonel Charles Brubaker (James Brolin), Lieutenant Colonel Peter Willis (Sam Waterston) and Commander John Walker (O.J. Simpson) – are on the launch pad readying for take-off when the hatch of the capsule is opened and they are hurriedly bundled out. NASA specialist Dr. James Kelloway (Hal Holbrook) explains that they have discovered that the life support system supplied by an outside contractor is faulty and that if the launch went ahead all three astronauts would be dead within three weeks. But the space programme has fallen on difficult times and they need the mission to be a success in order to secure future funding. They have thus decided to launch the rocket anyway and fake the entire mission by transporting the astronauts to an abandoned Air Corps base, from where they intend to produce false transmissions from mock-ups of the capsule and the surface of Mars. The astronauts initially refuse to participate, but when Kelloway assures them that their families will pay the ultimate price for their non-cooperation, they reluctantly agree.

In conspiracy thriller terms, this does represent something of a deviation from the norm. Threats made by shady government departments or rogue military figures are certainly nothing new, but to find such wayward behaviour inside of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration is a rare thing indeed. Usually portrayed as adventurers and scientists driven by good intentions and the desire to explore, the suggestion that there are those within this hallowed organisation who would be willing to kill to protect their funding is an intriguing one.

It's established from an early stage that Kelloway is not working alone. It must have taken a sizeable team to construct the fake sets and rig the transmissions to convince onlookers that they were being projected across millions of miles of space. And let's not forget those involved in transporting the astronauts and concealing their departure from the watchful eyes of the public, the press and the men's unknowing families. After a while I began to suspect that, despite Kelloway's assertion that almost nobody knows about this deception, the only NASA department not in on it was Mission Control, who from the moment the rocket departs appear to be buying the whole thing as real. Here, of course, lies the weakness in Kelloway's plan, the assumption that in a room full of super-smart and dedicated people, none of them would spot that something is amiss. And that's just what happens when savvy technician Elliot Whitter (Robert Walden) discovers that the astronauts' transmissions are reaching Mission Control ahead of the spacecraft's telemetry, information he immediately takes to his supervisor, who quickly dismisses his findings as the result of a technical malfunction they've been aware of for some time (shouldn't you have got that fixed before the first manned mission to Mars?). Whittner is not convinced, and that evening voices his concerns to his TV journalist friend Robert Caulfield over a beer and a game of pool. Initially the information falls on distracted ears, but when Whittner disappears, along with all trace that he ever existed, Caulfield launches an investigation that puts his own life in peril.

If it seems like I've given away a lot of the plot then let me assure you that while in some ways I have, this is effectively all set-up, and I've deliberately not mentioned the big midway twist that drives the film's second half (you won't have to look far if you want to know what it is). As a 'what if?' conspiracy thriller it's enthralling stuff, and the pace at which it unfolds, accelerated further by Jerry Goldsmith's driving score, makes it easy to turn a blind eye to a sprinkling of sometimes gaping logic holes. Pace is everything here, kicking the story off in the opening minutes and moving from one incident to the next with barely a pause for breath. Which is all well and good. The twists are nicely devised, a fair few of the dialogue scenes are neatly written and performed, and some of the set-pieces are genuinely exciting.

Where the film falters a little is in its characterisation. In his determination to get and keep the story moving as quickly as possible, writer-director Peter Hyams introduces characters only when they the plot requires them to appear. There are precious few character establishment scenes, and I had the sneaking suspicion that we are being asked to bond with people largely because they are played by instantly recognisable faces. Thus we're expected to connect with Charles Brubaker because he's played by James Brolin, and we liked him in Westworld and Marcus Welby M.D., and with Robert Caulfield because he's played by Elliot Gould. And you know Elliot Gould, don't you? That guy from M*A*S*H and The Long Goodbye? Of course you do. As a result the characters have precious little depth, and I have a feeling that I only really bonded with them at all because they are put in situations that we as film viewers have responded to for many years. Thus when the brakes on Caulfield's car fail and he is sent hurtling through traffic at death defying speeds (visibly so – the film has been all too clearly speeded up in places), the tension is created by the filmmaking alone rather than any personal investment we have in Caulfield's fate. And we want him to succeed in his quest because we love to see the well intentioned little guy win out against corrupt and murderous people in positions of ultimate power, whatever the noble acronym of their corporation.

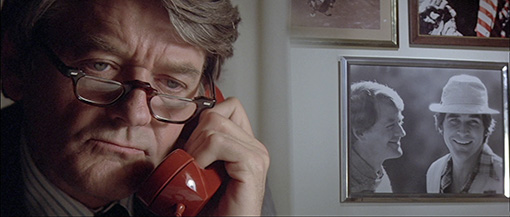

Which is a bit of a shame, as when your cast is this good and you do give them a scene that allows them to show their metal then they really deliver. The speech delivered by Hal Holbrook as Kelloway to the astronauts explaining why they've been pulled from the craft makes for compelling viewing, despite being delivered at some length in a single slow track to close-up. And the scene in which Caulfield first questions Brubaker's wife (presumed widow) Kay, nicely played by Brenda Vaccaro, is most convincingly handled, largely because Hyams allows the conversation to unfold in a believable manner, complete with all of Caulfield's carefully worded assurances and Kay's curiosity-driven questions. Perhaps my favourite such sequence comes when Caulfield tries to convince his boss Walter Loughlin (David Doyle) that he's on to a big story, only to have the man smilingly mock everything he says. A funny scene in itself (Doyle is a treat here), it also provides a little sorely needed backstory and a crying wolf reason for Caulfield's lack of editorial support.

In the end Capricorn One easily gets by on its breezy pace, its neat plot twists and its breathless set-pieces – a late film chase involving a crop duster and two helicopters boasts some of the most hair-raising aerial stunts and camerawork I've ever seen (on the big screen it's genuinely stomach-churning), all of which I recall from my first viewing of the film back when it was released in UK cinemas. What I didn't remember is how well written and handled some the later dialogue scenes are, good enough at times for me to wish I'd been allowed to get to know these people before I was being asked to fear for their fate. The film's underlying concern about not trusting the information and images fed to us by press or government, however, still comes through intact and is more relevant than ever.

Network has delivered a generally strong 2.35:1 transfer that shines when the light levels are at their most favourable, with a generous contrast range that hangs on to the black levels without punishing shadow detail and boasts a pleasing rendition of the naturalistic colour palette. The level of detail is very good, particularly on daytime exterior wide shots (Hyams is fond of these), the film grain is visible without being distracting, and the image itself is spotless, as you'd hope from a recent restoration. There are, however, a few occasional drops in quality, notably on what I'll coyly refer to as the desert hunt sequences and specifically shots involving two helicopters. On a few of these there is a marked increase in grain and loss of sharpness that indicates the frame has been enlarged, which is an editing decision and perfectly understandable. But on a few others there is a colony of indistinct blobs at the top of the image that move with the camera, suggesting either that there was dirt on the camera lens (which seems unlikely on such a project) or something went a little awry at the processing stage. It could also be a fault that crept in during the transfer from film to digital, but why just these shots, and by association this particular camera at this one location?

It's also worth noting that there is a brief encoding glitch near the start of the film on the review disc. Normally I wouldn't mention this, as such issues are usually sorted before the release version, but this one has apparently crept through onto a few copies of the retail Blu-ray. If you do end up with one, Network are offering to replace them (see below**).

The Linear PCM 48K stereo soundtrack is in very good shape, having a most reasonable dynamic range for a film of its time, although don't hold your breath for room-shattering bass. The dialogue and especially the music are always clear, and there are no traces of damage and not a hint of background hiss.

Optional SHD subtitles have been included.

Theatrical Trailer (3:09)

A really seductive and well assembled trailer that has a few too many spoilers to be watched just before the movie itself.

What If...? The Making of 'Capricorn One' (6:49)

Made at the time of the film's production and fluffy in its image quality, this is essentially an EPK but with a surprisingly (and pleasingly) cynical edge, as a number of the actors suggest that you can't really trust the government on anything, while Peter Hyams plays the straight man and provides an outline of the plot and characters. There is also a fair amount of footage of the shoot itself, including material not included in...

Desert Filming (38:21)

You see, this is why we have editors. What we have here is a collection of behind the scenes footage of the prep and the shooting of some of the desert scenes, which while definitely of interest and of a very decent length is presented here in its raw and unedited state. Thus useful long-held shots are mixed with ones that last only as few seconds and contain little of value and include comments made by the sound recordist or cameraman. And every single one of them is headed or tailed by the annoying beep of the device used to synchronise the picture to the sound. And there are a lot of these to contend with. Fortunately there is more than enough good stuff here to make it worthwhile.

Studio Filming (4:07)

More unedited rushes, this time of the prep for the fake Mars surface set scene. Useful for the footage of Hyams directing James Brolin (whilst someone sings in the background), and easier on the ear because the crew used mic taps to synchronise the sound.

Gallery (4:06)

A rolling HD gallery consisting of a few posters (good ones, too) and a lot of publicity photos.

I've always held Capricorn One in higher regard than my fellow lead reviewer Camus, who never felt that the elements successfully gelled into a complete movie, and watching the film again there were definitely times when I really did get where he was coming from. But despite the lack of depth to the characterisations, I still enjoyed the film for what it is, a sometimes implausible, perhaps insubstantial, but rather exciting conspiracy-driven action thriller. It may seem an odd inclusion in Network's 'The British Film' collection, given it's American setting, director and cast, but it was produced by ITC, the British TV and film production and distribution company behind such classic cult favourites as The Champions, The Prisoner and Thunderbirds, to name but three. The transfer is generally fine, and the extra features, although unpolished, are certainly of interest. Recommended.

* This conspiracy theory surrounding the moon landings has been around for decades and still refuses to die, despite the fact that just about every piece of evidence offered to support the theory has been soundly debunked. You can find a list of them and more at the Moon Landing Conspiracy Theories Wikipedia page here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moon_landing_conspiracy_theories

** From Network's Facebook page: "It has come to our attention that a small number of the initial shipment of the new Capricorn One Blu-ray have a picture fault which is visible on certain home video setups. If you believe that you have one of these discs then please contact us directly at shop@networkonair.com with your contact details and where you bought the Blu-ray."

|