|

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power began life as a presentation given by American filmmaker Nina Menkes at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, “Sex and Power: The Visual Language of Oppression”. Large parts of this film are just such a presentation by Menkes, with shots here and there of the audience. (And yes, there are men as well as women in attendance.) Menkes’s thesis is that there is a visual language to films, specifically with regard to women on screen. And for the next hour and three quarters, that’s what she explores. She begins with a quote from James Baldwin: “Not everything can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

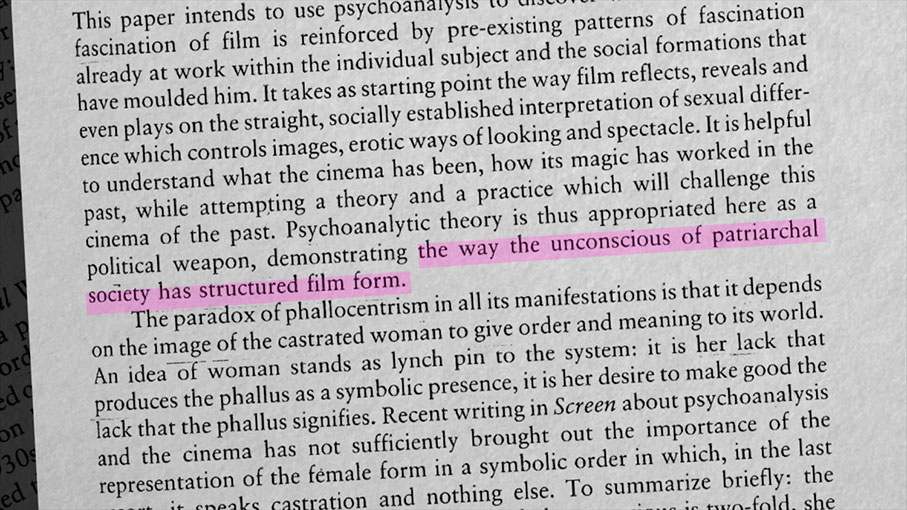

Shot design is gendered, she says, and men and women are consistently filmed differently. And from that difference springs two other issues: employment discrimination against women in the industry and pervasive sexual harassment, abuse and assault. Her jumping-off point is Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. Menkes describes Mulvey as “the original gangster film theorist” (would Mulvey call herself that?) who identified what became known as the “male gaze”, something mentioned just once in the essay. Mulvey described the gaze, the camera eye of the director and cinematographer, and the view of the audience, as specifically male and heterosexual (and cisgendered). To illustrate her points Menkes shows clips from around 175 different films.

To achieve this male gaze, Menkes identifies five different methods. The first is subject and object, men and women respectively. In films, and in cinemas, men watch, and women are watched, and the framing of shots encourages that. An extreme example is the 1947 film Lady in the Lake, of which almost all the film is shot with subjective camera, so is a male gaze looking at everything, women especially, for the duration of the film. The second and third are framing and camera movement. It’s often not women as a whole we see as so very often it’s a part of the woman we see: her lips, her breasts, her buttocks, her legs. It’s a sexualised view and not one that the gaze has of men, who are filmed usually in action. Sometimes this gaze is not presented as that of one of the characters onscreen, so it is that of the camera itself. If, for example, slow-motion is used it’s to linger on the women, but to emphasise men as they fight or are otherwise in motion, active rather than passive. It’s because of this male-mandated standard of beauty, Menkes suggests, that many women suffer anxiety and self-hatred.

The next is lighting. Men are often lit in three dimensions (in a usually 2D medium, mind) while women are lit in a softer way, flattening out those dimensions. Finally, narrative position. Menkes uses a scene from Raging Bull where Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro) and his friend (brother, actually) Joey (Joe Pesci) are talking while in the distance, Vickie (Cathy Moriarty) has caught Jake’s eye. We get the 3D versus 2D lighting again, and also Vickie’s voice is inaudible, despite her being close enough for the two men and us to hear her. These principles, Menkes says, have been in cinema for a long time. She uses as an example Metropolis, a favourite film by her, with a scene of an erotic and scantily-clad dance.

The second vertex of Menkes’s triangle is employment discrimination. From the sound era to the 1970s, just two women solo-directed feature films for US major studios: Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino. Interviewed about this is Maya Montañez Smukler, whose book Liberating Hollywood profiles the (count them) sixteen women who directed feature films in the US, for majors or independently, throughout the decade of the 1970s, and the two who worked independently in the 1960s. Nowadays, women directing films are more common: I’m writing this as the largest-budget film ever made by a woman opens in cinemas. However, to work, women often have to make “men’s films”, and the first woman to win an Oscar for directing, Kathryn Bigelow, did so with just such a film, The Hurt Locker. At present, the proportion of students at film school is roughly 50/50 male and female, but that isn’t reflected in the numbers of those who go on to work in the industry.

The third vector is sexual assault and harassment, something current in recent years with #MeToo and Time’s Up. Menkes produces a statistic that ninety-five percent of women employed in Hollywood have suffered sexual harassment or worse, and suggests that women being objectified in films has led to this, with glamorisation of sexual assault and implications that a woman’s no actually means yes. Some of the interviewees report threats if they didn’t appear nude or perform sexual scenes, possibly to the extent of ending their careers. If the boot is on the foot, with a woman looking at a man and coercing him into sex – Menkes uses a clip from Mandingo – it’s an expression of power but not sexuality and the man is not sexualised despite his being used as a stud.

Inevitably there are quibbles. Some of these films were directed by women: for example an erotic dance in Julia Ducournau’s Titane, or the opening close-up of Scarlett Johansson’s knicker-clad backside in Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation. Menkes doesn’t comment on this fact until later in the film, so is she suggesting that Ducournau and Coppola and others are complicit in the patriarchal gaze of mainstream cinema, in short complicit in misogyny? Menkes does talk about the cinema of queer directors (male and female) and how they may do things differently. Pedro Almódovar might slowly pan across a male body, for example, filming him in a way that many women are filmed, while a woman looking at another woman, in Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire, the power dynamic is different. The latter is contrasted with other scenes of lesbian sexuality, such as Abdellatif Kechiche’s Blue is the Warmest Colour. That film is mentioned in the section dealing with harassment, abuse and coercion of women into nude/sexual scenes, with Léa Seydoux’s comments on Kechiche’s tyrannical behaviour on that film and his use of alcohol to facilitate unsimulated sex scenes in his follow-up Mektoub, My Love.

There’s also a question of context to some of these clips, which are presented outside of one. No director, male or female, gets the right to reply, though Menkes has said that many were approached but declined to be interviewed, one reason why the interviewees in the film are almost all female, with at least one non-binary person (Joey Soloway). Finally, Menkes uses examples of her own films as demonstrations of ways to bypass the usual patriarchal gaze. So is she suggesting that she (and some others) knows the right way to do this? It has to be said (see the Q&A on this disc) that she regards this question as misogynist.

There’s undoubtedly a lot of truth in Menkes’s thesis, and much that should not go unsaid, but often is. And if the purpose of a polemic is to provoke discussion and possibly argument, it certainly does. The film ends with a quote from Agnès Varda: “The first feminist act is looking. To say, ‘OK, you’re looking at me. But I’m looking right back.”

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power is a Region B Blu-ray release from the BFI. The film has an 18 certificate.

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1. Brainwashed has existed in the digital realm from the outset, other than the fact that most of the films extracted were shot in 35mm, and those clips respect the original aspect ratios and are of good visual quality. The lecture footage and animations were digitally captured. So you’d expect it to look pristine, and it does.

There’s a choice of two soundtracks: LPCM 2.0 and DTS-HD MA 5.1. I listened to the latter and sampled the former. You won’t find much difference between the two, which use the surrounds mainly for the music score and extracts from films which had stereo soundtracks (for example, the Playmates scene in Apocalypse Now). English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available for the feature only.

Commentary by Nina Menkes and Cecily Rhett

A track with the producer/director and editor of the film. You may wonder how you could discuss a film like this without much description of what’s on the screen in front of is. Given the discussion of the use of slow motion, Rhett likes the shots of Menkes walking to the lecture theatre at Cannes as “a warrior going to battle”. They talk about how they sourced the clips, which are included under US copyright law as “fair use”, with legal advice as to how much commentary over each clip would count as review or criticism and hence fair use. Having to license each clip would have made the film unfeasible.

Nina Menkes Q & A (31:26)

This was filmed at the BFI Southbank after a screening of Brainwashed, with Nina Menkes interviewed by writer and BFI curator Rachel Pronger (also co-founder of the feminist film collective Invisible Women). Menkes talks about how the internet and Google searches made research possible, so “young girl sexualised on film” led her to Pretty Baby, for example. Menkes answers questions from the audience, which appear on screen as text captions.

Theatrical trailer (1:45)

How do you sell a film like this? Answer, you use extracts from Menkes’s lectures giving the main points of the film, some of the illustrative clips and critics’ quotes.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing of this release only, runs to twenty-four pages. It begins with Nina Menkes’s director’s statement, in which she outlines how the film came about and her aims for it. Sarah Wood contributes an essay which begins by marvelling that Laura Mulvey’s essay is now almost half a century old, but its relevance is ongoing as following progress there is conservative pushback. This is nothing new: Susan Faludi’s book Backlash, describing this very phenomenon, came out in 1991. #MeToo has had its own pushback in its turn, with major feminist gains being overturned, for example the US Supreme Court’s revoking of Roe vs Wade. Menkes does say that she is not criticising Kathryn Bigelow, say, but states that she is part of a system. Wood also says that the cinema’s gendered view is present in other media, and she uses AI to prove that.

Kenneth Reveiz begins their essay by saying that Brainwashed is the most important film ever made and later calls Nina Menkes a genius. They don’t say much to back up this claim, to be sure, other than crediting their thesis second reader as to what they mean by “genius”. After a list of the film credits, Sophia Satchell-Baeza contributes an interview with Menkes reprinted from the May 2023 Sight & Sound, which covers her previous films, which aren’t covered much in this release, other than the clips shown in the main feature. They could be called experimental, but Menkes rejects that label. Also in the booklet are notes on the special features, and several stills.

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power is a polemic, intended to state a case. Although you might not agree with all of its conclusions, there is no doubt that classic narrative cinema, from early days to the present, in Hollywood and other countries, is often highly sexualised and Menkes makes a case for this to lead to employment discrimination against women and a pervasive culture of sexual harassment and worse.

|