|

London. Sylvia (Anne Raitt) is a secretary for an accountancy firm. Her best friend there is fellow secretary Pat (Joolia Cappleman). Outside work, Sylvia is the sole carer for her mentally disabled, twenty-nine-year-old sister Hilda (Sarah Stephenson). She meets teacher Peter (Eric Allan) and begins a tentative relationship with him...

Bleak Moments was Mike Leigh’s first feature film, after some short films. Fifty years on, it stands up well, both in its own right and in the ways it looks forward to his later work. While not without flaws, it belies Leigh’s lack of experience behind the camera.

Leigh was born in 1943, a doctor’s son, and brought up in Salford. Les Blair, who produced and edited Bleak Moments and went on to become a director in his own right, was at school with him. With a scholarship to RADA in 1960, he moved to London, and his adoptive city became central to much of his work. As an actor, he mostly worked on stage in repertory, though in 1963 he had his first and almost only credited role on screen playing a mute boy in an episode of Maigret. (He also apparently has an uncredited role in West 11 the same year, but as I haven’t seen that, I can’t comment further.) He soon moved away from the stage and worked in theatre. Inspired by John Cassavetes’s film Shadows and Peter Brook’s celebrated stage and later film production of Peter Weiss’s The Marat/Sade, he began his interest in developing plays not from an original script but via a series of workshops and improvisations with his cast. At the end of this process, a final script was produced and the play put on. (Contrary to what some would have you believe, Leigh’s plays – and later films for both cinema and television – are not improvised in the final performance or on set, as there is a firm script by then. This is different to Cassavetes’s methods, where he did have his cast improvise on camera.) One such play was Moments, put on at the Open Space Theatre in Tottenham Court Road in 1970. The play had a cast of five and one set, but even so, Leigh thought that it should be expanded to become a film.

Les Blair wrote to various bodies and individuals looking for financing for what would inevitably be a minuscule budget. One of those individuals was Albert Finney, who put up almost all of the £18,500 budget (£100 came from the British Film Institute Production Board). Finney’s name isn’t in the credits, but the name of his production company, Memorial Enterprises, is. Finney also supplied the production with short ends from recent Memorial Productions, as this was still a 35mm shoot despite the budget. The major part of the budget was film stock and processing. The film was shot in early 1971 with Sylvia’s house and neighbourhood a real one (with some production-design tweaks) in Tulse Hill. The cast and crew got themselves to the shoot by their own means – no drivers here – and there was no catering, with the production eating at a cafe around the corner.

Leigh is credited with the scenario rather than taking a standard writing credit as well as his directing one: it would be “devised and directed by” for his television work, but union rules meant that when he returned to cinema filming his credit would have to be “written and directed by”. There’s an inaccurate impression of much of Leigh’s work that he is wallowing in his character’s misery. That isn’t true, on the whole, though putting the word Bleak in his title was possibly asking for it. (Similarly his first Play for Today, which he called Hard Labour.) His empathy for the majority of his characters is palpable, however awkward and sometimes annoying they can be. They are often in pain, and many of Leigh’s films build up to an ending that’s a catharsis rather than a conventional plot resolution: a boil is lanced, the pain let out, and there is hope that the characters can rebuild their lives. That said, there is humour in Bleak Moments, not least in Sylvia’s habit of coming out with jokes at not always the most appropriate moment. (The use of jokes as a way of avoiding deeper feelings is a trait that other Leigh characters have had, though here it’s unusual for being located in a female character.) Leigh himself summed this film up, less than seriously, as “Antonioni with jokes”. The characters are all in their different ways find it difficult to communicate with each other, for reasons of disability in Hilda’s case, emotional repression for the other characters. Leigh stages their interactions for maximum awkwardness, often holding shots intentionally just a little too long, so silence expands to fill the gaps. There’s no music score. Even body language is hard to manage: when Sylvia and Peter have a restaurant meal, they’re sitting side by side instead of facing each other. Leigh is an admirer of Yasujiro Ozu, whose films he first saw when he moved to London: he included Tokyo Story in his top ten in Sight & Sound’s 2012 poll. Like Ozu, he often stages the action in front of the camera, which is usually static or at most moving almost imperceptibly to follow the characters. The few times the camera moves more overtly – such as a handheld shot keeping up with Pat as she walks along the street – it comes as a visual jolt. The cinematography by Bahram Manocheri (spelled Manoocheri in the credits) is impeccably naturalistic. Working as a camera assistant was Roger Pratt, who later shot Leigh’s Meantime and High Hopes and the eighteen-minute The Short & Curlies, having become a leading cinematographer in between with Brazil, Mona Lisa and others.

Anne Raitt and Sarah Stephenson didn’t work with Leigh again, but many others in the cast did so. Nowadays, it might be an issue that Hilda and the other mentally disabled adults at the remedial centre are all played by non-disabled actors, for all the obvious research they did. The film doesn’t underplay the toll that being Hilda’s carer has taken on Sylvia and on others, and with the fraught undercurrents between work-colleagues-become-friends Sylvia and Pat. Sometimes Hilda effectively becomes a bargaining chip between the two.

Bleak Moments premiered at the 1971 London Film Festival before going on release in May 1972, to good reviews but not much in the way of box office. By then, the British film industry was in a downturn, as the investment from American major studios on which the production boom of the previous decade had gone away. It would be seventeen years before Leigh made another cinema feature. In between then, he worked on television, the next film being the twenty-minute piece for BBC Schools in 1973, A Mug’s Game? on the dangers of gambling, which included Eric Allan in the cast. (A Mug’s Game? still exists, but did not appear on the BBC’s box set from 2009, Mike Leigh at the BBC.) The same year, he made his first Play for Today, Hard Labour, starring Liz Smith (who has a small role, her screen debut, in Bleak Moments as Pat’s mother), and his reputation grew over the rest of the decade and much of the next, with his work for the BBC and, in 1983 for Channel 4 with Meantime, before he returned to the big screen in 1988 with High Hopes.

Bleak Moments is released by the BFI on an all-regions Blu-ray disc. The film had an A certificate on its cinema release and is now a PG (it’s the only contemporary-set Leigh cinema film where no-one swears). However, Leigh does let slip an F-word in his commentary and the interviews, which might have given these items a 12 if they had been submitted to the BBFC.

The film was shot in 35mm. The Blu-ray transfer is based on a scan and remaster in 4K resolution of the original negative, in the ratio of 1.66:1, approved by Leigh and his longstanding DP Dick Pope. The cinematography is intentionally naturalistic, and is sharp with strong, if not bold, colours and natural grain.

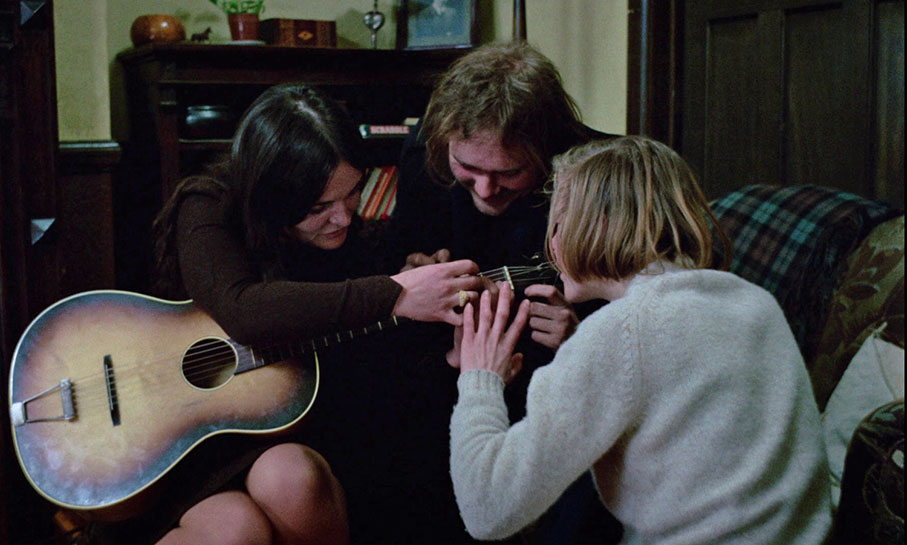

Bleak Moments was released in cinemas in mono. Leigh in his commentary apologises for the quality of the soundtrack, which more than anything else reflected the film’s low budget. It has been cleaned up for this Blu-ray and is presented in both mono (rendered as LPCM 1.0) and a newly remixed stereo version, playing in surround (LPCM 2.0). There’s frankly little difference between the two as the film is very much driven by dialogue. The only piece of non-diegetic music is Chopin’s Nocturne E Flat (Opus 9 number 2) for solo piano, over the opening credits. The rest of the music is all diegetic, including the same piece played by Sylvia near the end of the film on a very out-of-tune piano, and drug-related folk songs played on an acoustic guitar by Sylvia’s neighbour Norman (Mike Bradwell), some of which were written by the actor. In the stereo track, the surrounds are used for ambience. There are English hard-of-hearing subtitles available on the feature.

Commentary by Mike Leigh

This was recorded in 2008 (not 2015 as the booklet says, or at least it does in the PDF copy I was sent to review) and featured on Soda’s DVD release, which he mentions towards the end. Oddly, the commentary wasn’t included in the Bleak Moments disc in Spirit Entertainments’s 2009 box set The Mike Leigh Feature Film Collection which included all of his feature films (including Meantime) up to that point.

Leigh is proud of his work in this film, though he does have a tendency to describe particular scenes in his own work as “famous” and “epic”. He does however acknowledge the film’s shortcomings, some due to budget and some due to inexperience, including scenes he would now have shot differently. He does impart a lot of information on how this tiny-budget film was made, including some unexpected ones. (After the film was released, he was presented with a bill for the use of the in-copyright song “Freight Train”, sung and played in the film by Mike Bradwell. Albert Finney paid for the song’s use.) Leigh’s commentary is worth listening to.

In Conversation: Mike Leigh and Les Blair (27:41)

This was shot on rather noisy black and white video in 1972 as part of the University of London’s In Conversation series. The interviewer is David Sharp. Much of the talk is on how low-budget films are made, with specific reference to Bleak Moments, and there is talk of the film’s distribution. It played at the Paris Pullman, which was in Chelsea so not in the West End, and taken off once the audiences began to slacken off. The cinema was owned by the film’s distributor who seemed to be more in favour of releasing good films rather than making money, or “bread” as Leigh calls it more than once.

Interview with Mike Leigh (35:40)

This was recorded in 2019 at the Riverside Cinema, Woodbridge, after a showing of Nuts in May. Also on the programme was A Light Snack, one of the five Five Minute Films that Leigh made in 1975 but which were not shown until 1982. Those showings were part of a BBC2 Leigh retrospective, which included an Arena documentary on him and when I first saw many of Leigh’s films. (All of these, including the documentary, can be seen in the BBC DVD set Mike Leigh at the BBC, which came out in 2009 and is still in print.) The Q & A is conducted by Neil McGlone. Much of the discussion is about Nuts in May, which came about because Dorset-born BBC commissioner David Rose asked Leigh if he could make a film set in his home county. As both films on the programme were made for television (although shot on 16mm) Leigh does talk about how the British film industry, for the type of films he wanted to make, was almost always in television at the time. It was David Rose who took the idea of giving the films a cinema life before they turned up on the small screen to Channel 4 when it started up and it began to fund British films, including several of Leigh’s.

The discussion ranges over Leigh’s career and then he takes questions from the audience. The sound quality for those questions isn’t great, but fortunately Leigh or McGlone repeats them for the benefit of the audience and in a few places the questions seem to have been edited out.

Bleak Moments: 50 Years On (9:08)

A new interview with Leigh, as he looks back at his film, describing its inception as a play and its expansion to the final feature, illustrated by clips. This works as effectively a capsule version of his commentary, which was recorded thirteen years earlier, as it does repeat much of the same material. However, he does talk about the film’s use of music, as Bleak Moments and his next two feature-length films, Hard Labour and Nuts in May, don’t have scores, and does point out that the soundtrack has been cleaned up for this new release. He sums up by saying that the film is undeniably an acquired taste and the work of younger people but he still thinks it works and is proud of it.

Image gallery (1:43)

A self-navigating selection of production stills (all in black and white), plus two poster designs.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available in the first pressing only, runs to twenty pages. The essay, by Ellen Cheshire, sums up much of the response to Bleak Moments on its first release, “Never heard of Mike Leigh?”. In fact, that’s what Roger Ebert openly said in his review. Cheshire covers Leigh’s early life and career, including his school friendship with Les Blair, up to his debut in the theatre in 1965 and five years later, the original play version of Bleak Moments, with the cast of five being the same lead actors as the film. In addition to talking about Leigh’s television work, Cheshire pays some attention to his stage productions, which continued into the 1990s and then into the twenty-first century with Two Thousand Years (2005) at the National Theatre and Grief (2011) with his frequent collaborator Lesley Manville, and ends by pointing out moments in Bleak Moments which seem to foreshadow later work.

It’s a mark of the critical attention Bleak Moments received that not just the Monthly Film Bulletin but also Sight & Sound reviewed it, and David Wilson’s review for the latter is reprinted here. Also in the booklet are notes on and credits for the extras, and stills.

Bleak Moments was Mike Leigh’s debut feature for the cinema, and it would be seventeen years before the next. Fifty years after the film was made, it holds up very well, despite shortcomings largely due to the tiny budget, and it’s well presented on this BFI Blu-ray.

|