|

It’s interesting and sometimes unsettling how current world events can lend aspects of a film a whole new relevance decades after it was made. Take the opening sequence of the entertaining 1974 cross-genre curio The Beast Must Die, in which an unarmed black man is shown to be running for his life whilst pursued by a squad of armed and uniformed men who are directed by a controller who is monitoring his target’s every move via a complex network of CCTV cameras. Not comfortable viewing in the current climate. Then something unexpected happens. The man is found by one of his pursuers and has a rifle pointed at his head, but instead of being captured or shot is told that he can continue. This, and the fact that this is taking place in Scottish woodland instead of the streets of New York, gives the whole thing more than a whiff of Richard Connell’s influential and oft-filmed The Most Dangerous Game. The man continues running and once again is caught when a pursuer appears behind him and – after prompting from the man – shoots him in the back. Well, he would if his gun had any bullets in it. Finally, the man runs out of the woodland and onto the large and perfectly groomed lawn of sizeable country estate, outside which a group of well-to-do white individuals is sitting taking drinks at what looks like a social gathering. The man looks desperately at them for a few seconds and is then mowed down from behind by automatic gunfire, much to the horror of the startled onlookers. When they reach him however, the attack appears not to have inflicted any serious harm.

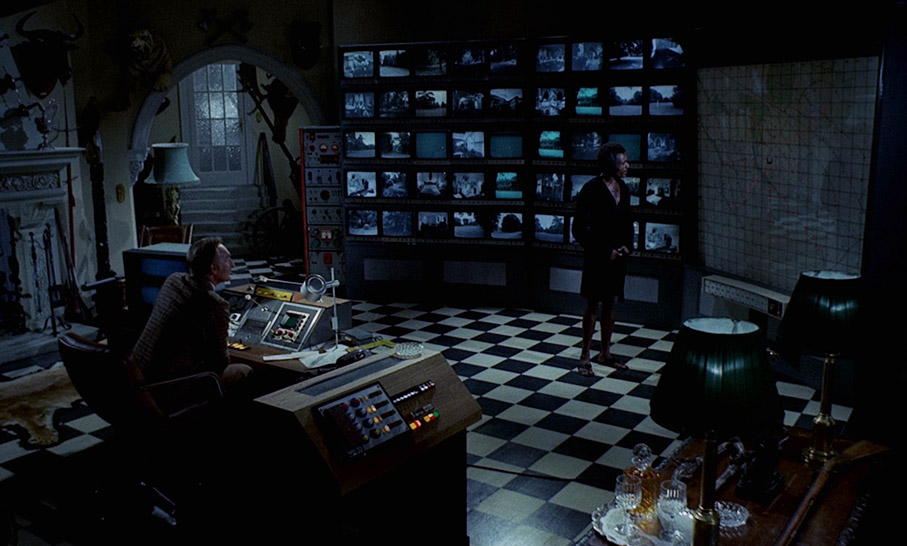

The victim’s name is Tom Newcliffe (Calvin Lockhart) and the man directing the operation to hunt him down is Polish surveillance expert Pavel (Anton Diffring), and in the very next scene the two are seen chatting cheerfully to each other. It quickly emerges that Newcliffe is a successful businessman with pots of money and that this whole exercise was designed to test out the effectiveness of the high-tech security system that Pavel has been hired to install and operate. Why does a man like Newcliffe need a setup elaborate enough to make even the most security-conscious Las Vegas casino envious? Well this brings us back to the aforementioned garden party, individuals that Newcliffe has invited to stay for a few days at his estate because he is convinced that one of them is a werewolf. He has his reasons. Three of them – Bennington (Charles Gray), Jan (Michael Gambon) and Davina (Ciaran Madden) – were each at the location of the violent death or mysterious disappearance of unnamed others, while Paul Foote (Tom Chadbon) has admitted to once eating human flesh, and all appear to have fallen from former grace as a result. Dr. Christopher Lundgren (Peter Cushing), meanwhile, has been invited because of his passion for the phenomena of werewolves, which he has made a detailed study of. The timing of this unusual social event is crucial, as the moon will be full for the next three nights and Newcliffe is convinced that one of his guests will transform into a ravenous beast, and as a big game hunter he relishes the chance to chase down and kill such a creature, one whose movements he plans to track with the aid of Pavel and his security system.

It’s an intriguing setup that melds elements of the traditional werewolf movie with an Agatha Christie-style country house whodunnit which it laces with action movie chases and gunplay. The decision to cast a black actor in the leading role and make him a successful and wealthy businessman certainly feels progressive for an early 70s British genre film, but while I’d love to believe that the filmmakers were following the genuinely colour-blind lead of George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, it’s confirmed in the extras that the decision was shaped by the international success of Shaft. This is echoed in composer Douglas Gamley’s funkadelic title music, and confirmed by the news that the screenplay was not written with a black leading actor in mind. Whatever the motivation, the filmmakers still deserve some credit on this front.

Back in my film school days I remember banging out a quick one-paragraph review of The Beast Must Die for the ‘movies on TV’ section of the college rag, and recall being a little dismissive of the film, despite saluting a couple of interesting elements and being amused by the late film ‘werewolf break’ (I’ll get to that later). Then again, that piece was written at a time when there were genuinely terrific and sometimes groundbreaking genre movies playing every few weeks at local cinemas. Start judging every horror feature by the standards of Suspiria, Shivers and The Hills Have Eyes, to name a few, and it becomes a little too easy to give short shrift to latter-day Hammer and Amicus titles. And yet just as one of classic-era Hammer’s final features – the Shaw Brothers collaboration, The Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires – was a cross-genre work that is absolutely worthy of re-evaluation, Amicus’s multi-genre horror swan song plays considerably better today than my fast-failing memory had convinced me it once did.

Not all of it holds up. A second chase sequence in which Jan jumps into his car and attempts to flee and is pursued across the expanse of the estate by Newcliffe in his Land Rover, is a largely gratuitous sequence that goes on long enough to feel a little like action padding and occurs too early in the story to build any real tension over how it will conclude. The werewolf, meanwhile, is a big dog dressed up in a hairy coat and appears to be so fond of its handler (who doubles for the actors when required) that shots of it attacking its human prey often look a tad too much like the playtime wrestling it doubtless was. On the surface at least, the characters are an interesting bunch, but I never got to know any of them well enough to get too concerned about which of them the werewolf might eventually prove to be, or to worry that much about the prospect of any of them being bloodily offed by the creature. Animal lovers, meanwhile, had best steel themselves for a thankfully short sequence in which the dog and the werewolf do battle, which the director admits in the extras was not faked but staged by getting the two animals angry at each other.

If all that seems a little damning then I’m probably overemphasising aspects that don’t come close to ruining what is otherwise an intriguing, well-made and rather enjoyable game of Werewolf Cluedo. The setup offers a neat twist on the traditional werewolf tale, and by focusing on the mystery and character interplay, first-time feature director Paul Annett ensures that the more well-worn elements of the sub-genre are effectively relegated to a supporting role, which has the unexpected effect of quietly reinvigorating them. His eye for camera placement is intermittently noteworthy, and considering there are times when Newcliffe is so annoying that I found myself secretly hoping he’d come a cropper, the film still milks a surprising amount of tension out of scenes in which he is shown stalking the beast by night. Mind you, he’s such a poor shot that I began to wonder if his big game hunter stories were boastful blarney – in the course of one pursuit he must offload a couple of hundred rounds from his machine gun at the beast, but all he manages to hit is his helicopter.

The cast is almost worth the price of admission alone. As Bennington, Charles Gray does the world-weary cynic act that by this point he had honed to perfection, Peter Cushing is in thoughtful professor mode and wearing a subtle Scandinavian accent as Dr. Christopher Lundgren, and Anthony Diffring is at his most enjoyably naturalistic as Polish surveillance expert Pavel. Best of all is Tom Chadbon as Paul Foote, a carefree, heavy-drinking bohemian artist who makes amusing light of just about everything, including almost killing his host with a bow and arrow. Given the progressive step off having a black leading man, it pains me to say that that Calvin Lockhart sometimes plays to the gallery when most of his fellow cast members are showing commendable restraint – when he gets angry I was occasionally reminded of The Art of Coarse Acting author Michael Green’s description of Shakespearean acting as one in which you deliver every line as if hailing a ship in fog. But it’s worth remembering that Newcliffe was clearly written to be a self-centred and arrogant prick with no regard for the feelings of others, including his long-suffering wife Caroline (Marlene Clark), and Lockhart absolutely nails that aspect of his personality. When it matters, notably in the quieter moments and the scenes in which he is stalking his prey or teasing his guests, he’s on fine form. I particularly liked his response to Bennington’s annoyance at being called out on his suspect past – “I don’t have to take that kind of talk from you,” say Bennington, to which Newcliffe smiling replies, “You just did.”

In his trailer commentary, Kim Newman makes a convincing case for 80s action movie tropes that get their first airing here, but coming back to the film after a gap of many years I was struck by the similarity of some sequences to those in more widely seen later films of note. The scene in which Newcliffe hunts the werewolf whilst being guided through a headset by Pavel anticipates the air shaft sequence in Alien, complete with electronic heartbeat proximity beeps and verbal warnings from Pavel that the creature is definitely around there somewhere and moving towards his employer. The two werewolf tests that Newcliffe runs on his guests – the first requiring each of them grasp a silver candlestick, the second (and more oddly erotic) to place a silver bullet in their mouths – plays a little like the blood test sequence in The Thing, and there are echoes in the actions of Blair in that film and Jack Torrance in The Shining in Newcliffe’s disabling of the vehicles of his guests to prevent them from leaving. I could even make a case, were I not avoiding spoilers, for how the final reveal of the werewolf’s identity has a lineage that runs through several films right up to a key episode of The Walking Dead, but that’s probably a discussion for another day. And given that the film was released in 1974, the security system installed and operated by Pavel – one that includes a wall of video monitors and cameras that watch every move made by Newcliffe’s guests and microphones that record their words – looks unsettlingly forward to a society in which we are watched by CCTV cameras almost everywhere we go and where our phones and other so-called ‘smart’ devices can be repurposed to allow the security services to listen in on private conversations.

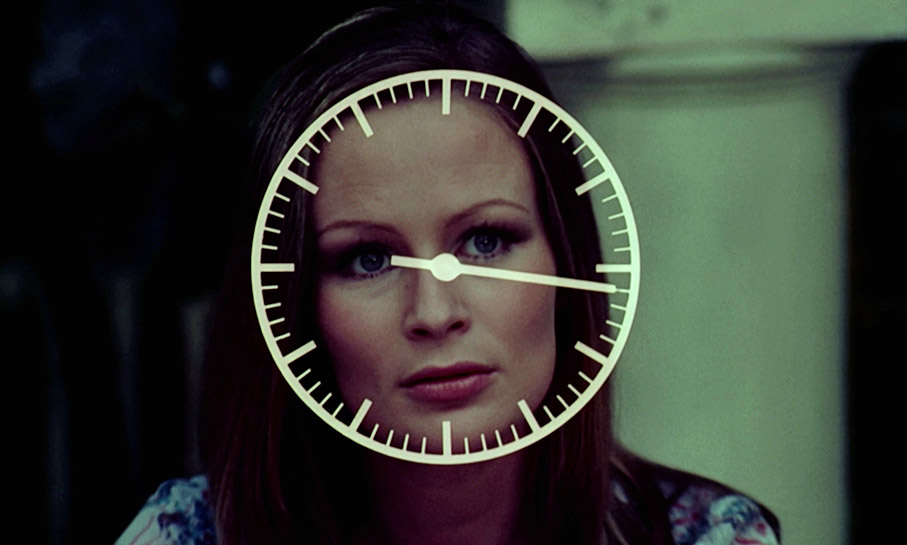

Of course, the film has become most famous for the above-mentioned werewolf break, a William-Castle inspired gimmick in which the audience is given 30 seconds to guess who they think the werewolf is, complete with a ticking clock graphic, Valentine Dyall narration and pictures of the suspects. This was not a scripted element and was added by producer Milton Subotsky at the editing stage without the knowledge of director Annett, who detests it to this day, and while I’m fond of Castle’s box of promotional tricks, it seems more obvious than ever that the film didn’t need it and that it disrupts the dramatic flow at a key moment in the story. That said, as long as you know that it’s coming then it fails to do any serious harm to the subsequent reveal and the impressively melancholic ending – like a fair few of Castle’s own works, there’s a lot more to enjoy and appreciate here than the marketing trick for which the film is most widely known.

A clean 1.66:1 1080p transfer from a StudioCanal HD remaster that recreates the moody dark nights and warmly hued days of Jack Hildyard’s atmospheric cinematography, nailing the black levels without sacrificing detail, though this is probably not the best film to watch in a sunlight-bathed room on a bright summer day. The day-for-night work is sometimes a little inconsistent even within the same scene, but I’m guessing this was down to how it was originally filmed and graded rather than an issue with the remaster. Detail is consistently crisp, brighter colours pop and there are none of the digital artefacts I have little doubt a DVD transfer would have struggled with in the striking early morning shot when Newcliffe walks out of the mist towards the house.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is also in solid shape, a tad restricted on its sonic range in a manner common to pre-Dolby films but with consistently clear dialogue and very decent reproduction of Douglas Gamley’s score.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available.

Audio Commentary with Paul Annett and Jonathan Sothcott

An engaging commentary with director Paul Annett, who is usefully prodded for information by author Jonathan Sothcott and who covers a lot of ground, some of it general, some of it related to what’s happening on screen. He outlines how he landed this, his first feature, and in the process reveals that Milton Subotsky hated the film and took over the editing, only revealing his decision to add the werewolf break to Annett shortly before the preview screening, a gimmick that ruined one of the best edits in the film (for confirmation, see the interview with Annett below). He talks about working with the actors, wanting to cast singer Shirley Bassey in the role of Caroline Newcliffe, the problems of creating a convincing werewolf, his offbeat first meeting with Peter Cushing, and a whole lot more. He admits to rewriting Michael Winder’s screenplay with his friend Scot Finch and wishing he had read the short story on which it was based (There Shall Be No Darkness by James Blish), as there are elements in it he would have included had he done so. He also reveals that the early car chase was added on Subotsky’s insistence and that he unsuccessfully made the case to the producer that the audience didn’t know either of the characters involved well enough to have any investment in the outcome, a point in which I am in complete agreement. For the first couple of minutes the soundtrack almost overpowers the commentators’ words, but this quickly settles down. A fine extra feature.

Archival Interview with Max J. Rosenberg (47:18)

An interview with Amicus co-founder and producer Max J. Rosenberg, conducted by author and producer Jonathan Sothcott in 2000 for the purpose of research rather than broadcast, which means that the audio quality is a little fluffy. Just occasionally you’ll have to listen carefully to make out what Rosenberg says, but for the most part I had no problem making out his words. Essentially, Rosenberg delivers a whistle-stop history of Amicus and its films, but it soon becomes apparent that his main focus is his former partner, Milton Subotsky, whom he clearly did not part with on amicable terms. Indeed, he spends a surprising amount of time highlighting what he clearly believes were Subotsky’s faults and failings, which reach a sort of peak when he recalls a time during the filming of The Skull when director Freddie Francis, whom he claims never usually swore, told Subotsky to his face that he was a cunt (his word, not mine). He certainly backs up Annett’s claim that Subotsky had a fondness for taking over films at the editing stage and then claiming he had saved them. It’s fascinating stuff, though there’s a frustrating moment for fans of Tales From the Crypt (that includes me), when Rosenberg describes it at the most important picture they made and seems to be gearing up to credit Subotsky’s love of EC comics for getting it off the ground when an interruption cuts this part of the interview short, and when we return it’s moved on several years to The Land That Time Forgot, so no mention here either of The Beast Must Die.

The BEHP Interview with Jack Hildyard (92:00)

Also playing in the manner of a commentary track, though with slightly better audio quality than the one above, is this British Entertainment History Project interview with cinematographer Jack Hildyard, which was conducted by filmmaker Alan Lawson on 7 January 1988. With a few prompts from Lawson, Hildyard takes us on a journey through his film career, from his early days as a focus puller and operator through to a number of his key films as director of photography. There are some interesting anecdotes along the way, including a stand-off with director Fred Zinnemann over the cruel treatment of kangaroos on The Sundowners (where his camera operator was none other than Nicolas Roeg) and a confrontation with Anthony Quinn regarding his rudeness in front of young women. There’s a saddening sign of the times when he claims that director Cavalcanti didn’t inspire confidence in his crew on the 1948 The First Gentleman because he was homosexual, and his curt dismissal of The Beast Must Die suggests he had no time at all for the film. The cameraman in me ensured that I found his clear explanation of the different lighting requirements for colour and black-and-white film and when and why he uses a light meter the most interesting parts, though I was intrigued by his claim that the requirement of a good director is that they should know how to ride a bike and properly boil an egg.

The BEHP Interview with Peter Tanner – Part Two (80:17)

Functioning as a generous fourth commentary track, this interview with editor Peter Tanner was conducted by filmmakers Roy Fowler and Taffy Haines on 6 August 1987 as part of the British Entertainment History Project and has the best sound quality of the three audio interviews included on this disc. The fact that this is labelled Part Two: 1939-1987 might on the surface seem a little confusing, as you won’t find Part One on any other recent Indicator discs, but worry not, it’s apparently coming on the label’s Blu-ray of I, Monster, a film that Tanner doesn’t have fond memories of working on. Personally, I’m now looking forward to that, as despite plenty of interesting talk about his later film career – and Tanner has worked on a wide range of prestige projects – it’s the tales of his early wartime work that I found most fascinating. And Tanner is an enthusiastic talker with clear and detailed memories of all stages of his many years in the industry, though thanks to this when I next watch The Cruel Sea I’ll be looking out for backwards-flying seagulls during a key scene.

Introduction by Stephen Laws (3:34)

Repeatedly at Outsider we find ourselves having to assure anyone reading our disc reviews that we wrote them before watching any supplementary material, only to end up banging our heads against any available hard surface when what we‘ve written is also stated almost word-for word in the extras. For the record, we take this approach in the hope that our views on a film will not be influenced by those of others, yet when our words are echoed so closely in the extras, that’s exactly what appears to have happened. I’d almost finished my review of The Beast Must Die when I sat down for novelist and Amicus enthusiast Stephen Laws’ concise introduction, and just a few seconds in was groaning at the realisation that he’d highlighted many of the very same elements and influences as I had, including my belief that the film plays better now than when I first saw it. He even connected the title music with Isaac Hayes’ Main Theme from Shaft through its use of ‘wacka-wacka’ guitars, the exact term I’d used and that I felt oddly guilted into removing from my first draft as a result. It’s actually a really solid introduction and I did learn something from it I didn’t previously know about the poster artwork, but damn you Laws and your perceptive observations.

Paul Annett – Directing the Beast (12:58)

Depending on which order you tackle the extra features, this enjoyable chat with director Paul Annett will either be enlightening or a repetition of various segments from the commentary. These include how he landed the job of directing the film, his desire to cast Shirley Bassey, his first meeting with Peter Cushing, and his response to the addition of the werewolf break and how it messed up one of the best cuts in the film, which here we get to see as it was meant to be (and it is good).

Super 8 Version (18:36)

Almost age-drained of its colour and compressing the film into a fifth of its original running time, this home viewing version replaces the main titles with a single cheesy graphic, and dumps the entire first 56 minutes (!), the character of Pavel and – a tad surprisingly – the werewolf break. The bare bones essentials are there, but what a way to see the film for the first time.

Theatrical Trailer (0:58)

A short trailer that builds itself around the idea that you have to solve the mystery of who the werewolf is, then disregards the specifics of the narrative by including almost everyone with a speaking part on the list of potential suspects.

Kim Newman and David Flint Trailer Commentary (0:58)

With just 58 seconds to make your case, David Flint barely gets a word in as Kim Newman states with real passion that “the werewolf is not very good but everything else about it I unreservedly love,” and makes a brief but solid case for its influence on later action movies.

Image Gallery

95 screens of sometimes pristine promotional and behind-the-scenes stills (including one of actor Marlene Clark displaying way more cleavage than she does in the film, and another of the principal cast members sitting down in the drawing room with a werewolf), posters and press book pages. Intrigued to see that it played on a double-bill with Brian De Palma’s Sisters (or Blood Sisters as it was titled in the UK).

Booklet

Following the expected credits there is an engaging and perceptive essay by Neil Young (the film critic, not the famed musician), who examines the film, the cast, the career of Calvin Lockhart, and the short story on which the film is based. He also made me realise I’d missed a trick by comparing the on-screen clock during the werewolf break to the one on the TV quiz show Countdown. Up next is an extract from a 1974 article on Amicus by Chris Knight from Outsider favourite Cinefantastique that was written as The Beast Must Die was nearing its release, and a really useful piece on author James Blish and his splendidly titled short story, There Shall Be No Darkness, extracts from which are reproduced to give an idea of how the film differs from its source material source material. A profile of lead actor Calvin Lockhart sourced from the film’s press book leads in to the expected extracts from two contemporary reviews. As ever, the booklet is generously illustrated with stills and press material.

The Beast Must Die is one of a number of British movies from the early 70s that helped to mark the death of old school period horror but that still seemed unaware of the direction in which the genre was heading. As the extras have confirmed, however, I’m not the only one who found himself enjoying the film more now than I did just a few years after its release. As ever with Indicator, the probability that the film will only be familiar to genre devotees has not prevented the label from sourcing a spanking transfer and lavishing the disc with quality special features. I’m not going to claim the film is a somehow forgotten classic, but this excellent disc still comes warmly recommended.

|