|

I like coincidences, as does my fellow scribe Camus, who delighted in one he discovered whilst researching for his review of The Devil's Men, also newly released on Blu-ray by Indicator, and that you'll find at the foot of the second paragraph of that review. Here's another small, film-related one for you. Having received four review discs from Indicator this month, Camus and I agreed to split their coverage between us. I took on Bartleby and An Unsuitable Job for a Woman, only to discover that both films open on a naturally lit mid-shot of their respective lead characters sitting in a train carriage as it trundles its way into Central London, looking wearily and distractedly out of the window. Both also occur immediately after title cards announcing the film's production companies and a few seconds of black screen, and are immediately followed by the opening titles. Here, the individual in question is the wiry Bartleby (John McEnery) of the title, and his expression and demeanour are those of a deeply lonely and unhappy man. On reaching his destination, he walks the streets of the capital seemingly unaware that the people he passes even exist. He moves as if in an alternative dimension, a post-apocalyptic one in which he is the only survivor, thrown into a state of shock by the sudden loss of everyone and everything that he has ever known, from which he lacks the strength and willpower to recover.

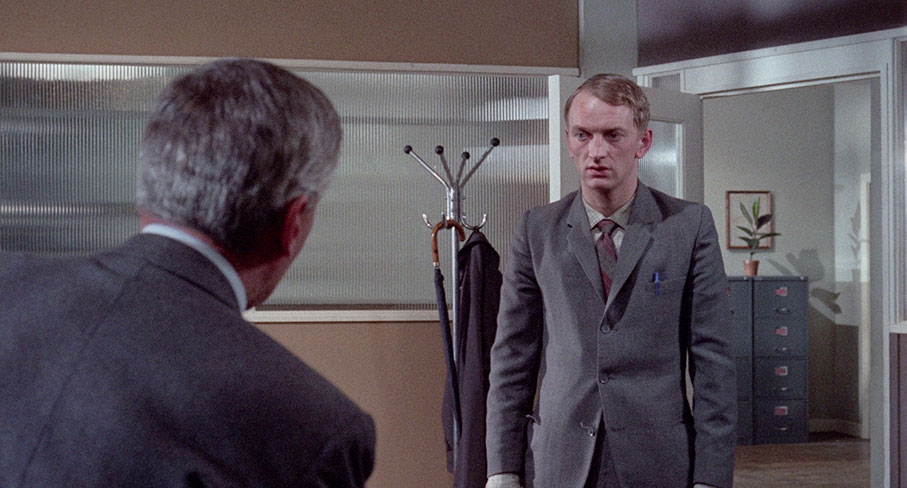

This sense of social dislocation is amplified by a soundtrack on which we hear him ticking off the information required on application forms for jobs he is heard applying for by phone, where his voice struggles to register with those to whom he is hesitantly speaking. Eventually, he rolls up at the office of a small accounting firm run by character referred to in the credits only as The Accountant (Paul Scofield), the first sign that we are meant to read at least some of what follows in allegorical terms. With no-one having so far been appointed to the vacant position of accounting clerk, The Accountant agrees to interview this quiet but smartly attired young man, and what follows could almost be used in business training as an example of how not to conduct yourself in a job interview. Bartleby is hesitant with his responses, lacking in enthusiasm, and intermittently fails to respond to The Accountant's questions at all, leaving them and his interviewer hanging in silence. When asked to talk a little about his background, Bartleby's response is to hand over the form he was asked to complete on his arrival and remark, "I put it all on the application." Clearly, verbal communication is not his forté. The Accountant is further confused by Bartleby's claim that the salary is not important and that "anything reasonable" will be fine. When asked if he thinks this job will suit him, he responds with a simple and almost mechanical, "I...will...accept."

I have to admit that on first watching the film, I cringed my way through the above detailed interview and genuinely couldn't understand why The Accountant would hire this insular young man on the basis of it. And here's where it gets tricky. So intrigued by the film did I become – I'll get to why in a minute – that I sought out the story from which it was adapted, one written in 1853 by Moby Dick author Herman Melville and titled, Bartleby, The Scrivener: A Story Of Wall-street. Temporal and locational shifts aside – and the story lends itself well to such alterations – this is an otherwise fairly faithful adaptation, albeit one in which some aspects have been shorn or slimmed down. Amongst these are the story's detailed descriptions of the firm's other employees and the thoughts of Bartleby's employer, from whose viewpoint the story is told. I learned from this, for example, that Bartleby's quiet and studious nature appealed to The Accountant and made a refreshing change from the annoying "eccentricities" of his other employees. Of course, this raises the oft-discussed argument that you shouldn't have to read the source material to understand a seemingly opaque aspect of the film adaptation, and it's a valid point. But I should also note that the interview is mentioned only in passing in the story, and is thus largely the creation of first (and to date, only) time writer-director Anthony Friedman and his producer and writing partner Rodney Carr-Smith. And it's such a wonderfully discomforting and character-shaping scene that the question of why The Accountant would hire Bartleby was one that I quickly shrugged off and moved on from.

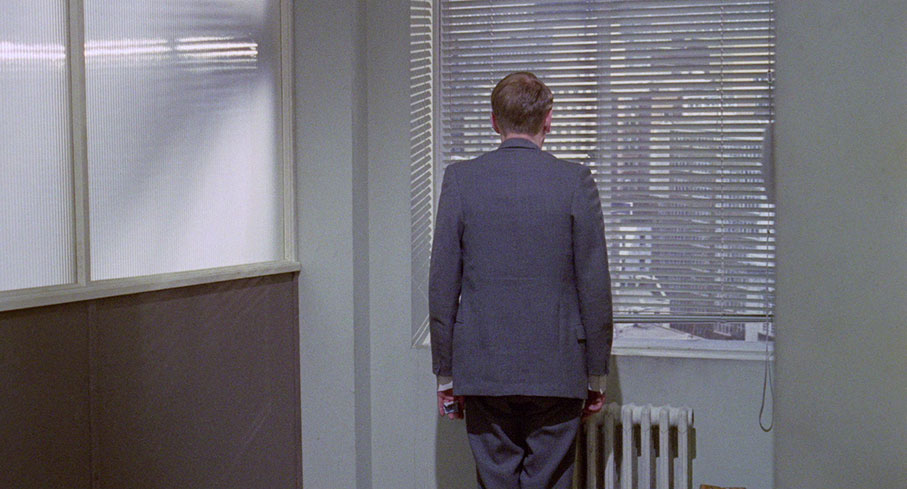

Once employed, Bartleby works alone at a desk just outside of The Accountant's office, and does so quietly and studiously. He is the subject of curious discussion amongst the other office workers, Tucker (Colin Jeavons), Dickinson (Tony Parkin), Miss Brown (Rosalind Elliot), and the unnamed Office Boy (Robin Askwith), and makes no effort whatsoever to interact with them. Then, one day, The Accountant asks Bartleby to bring the newly assigned Prebble file into his office for the two of them to discuss. "I would rather not, just now," Bartleby replies, then turns away and returns to his desk. This completely bemuses The Accountant, then infuriates Tucker when the Prebble file is assigned for him to work on instead. This proves to be the start of a gradual slide that sees Bartleby politely declining to do more and more work by repeating the phrase, "I would prefer not to," which eventually leads to him telling his employer, "I've decided not to do accounts anymore."

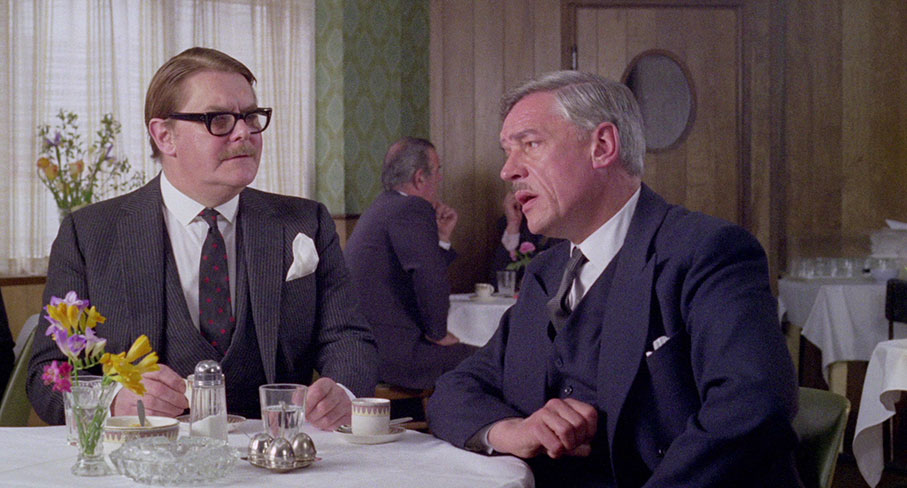

As a drama, Bartleby is strangely compelling, and I say strangely because the lead character – just like that of Melville's story – is someone I felt I was observing rather than identifying or emotionally engaging with. Indeed, for much of the time it's The Accountant whose views I found myself in sympathy with, even if his refusal to fire or even reprimand Bartleby when he refuses to carry out his assigned tasks seems to initially kick against normal business logic, and that's coming from someone who spent 25 years of his working life as a union steward. This reluctance on The Accountant's part is addressed in a brief scene in which he dines with a business colleague (Thorley Walters), during which he expresses an almost paternal interest in Bartleby's development and the belief that with the right sort of encouragement he could become a first-class clerk. Mind you, even this seemingly generous attitude is tested when he discovers that the reason Bartleby is at the office first thing and is always last to leave is that he has taken to living there.

In the exchange with his business colleague, The Accountant at one point identifies Bartleby's polite refusal to carry out certain tasks as a form of passive resistance, and herein lies the key to the most commonly observed allegorical reading. It's one that the director, in his interview on this very disc, admits was part of what attracted him to the idea of updating this 19th century story for film, but for those of you who enjoy exploring the subtext in movies, be warned, as once you get started here, it's hard to quit. Bartleby was made at the tail end of the 1960s, a time in which the counterculture flourished, fuelled in part by increasingly widespread opposition to the war in Vietnam. Timothy Leary's 1966 call (borrowed from Marshall McLuhan) to "Turn on, tune in, drop out" still resonated, and the generation gap had widened to a chasm. In this light, Bartleby is a symbol of both of the so-called drop-outs who turned their back on the capitalist system, and those who refused to fight in the Vietnam war. He is, as The Accountant observes, passively resisting, but against what is deliberately never made clear. In this analogy, it is enough just to resist, an action neatly illustrated when Bartleby responds to his employer's pleas with, "At the moment, I'd prefer not to be a little reasonable." In light of the fact the Melville's story is told from the viewpoint of Bartleby's middle-aged employer, however, what Bartleby may instead represent is the how the older generation perceived the non-compliant youth of the day, as disconnected, uncooperative, workshy, and almost impossible to communicate with. In this reading, The Accountant becomes a symbol of reason, of the more tolerant element of the older generation, and if even he can't bring the boy to his senses, what hope has anyone of doing so?

A third, more grounded reading largely dispenses with the analogous and instead sees Bartleby as a victim of clinical depression, a condition he exhibits – on the surface at least – many of the symptoms of. Quite what the cause might be is something shrewdly sidestepped by the film and the story alike, with Bartleby politely declining questions about his background or instead referring The Accountant to his application form, one whose contents are never shared with the viewer. What intrigues about this reading and continues to feel relevant at a time when mental illness in general is better understood and more openly discussed, is how the other characters respond to Bartleby's behaviour (and there are spoilers ahead, so skip to the next paragraph to avoid them). His colleagues are irritated by his insular nature and speculate that he must be epileptic or gay, while his employer takes an interest in his welfare and tries to help him, but remains bemused and frustrated by his refusal to conform. When he ends up in hospital, malnourished and uncommunicative, the doctors encourage him to eat and briefly put him on an intravenous drip, but otherwise leave him to his own devices and fate, an abandonment of duty and care that reawakened some painful personal memories for this particular viewer.

The casting of the two leads is pitch perfect here. Paul Scofield convinces completely as The Accountant, exuding a calm authority but completely selling the notion that he has taken a genuine interest in Bartleby's welfare and is unable to fire him because he is "so utterly civil, so dignified." His pained response on discovering that Bartleby is living in the office captures an entire paragraph of thoughts from Melville's story in a single, saddened expression, and it's this earlier attempt to understand and help that makes his later abandonment of these ideals feel like a betrayal. He's matched at every step by John McEnery's extraordinary performance as the titular Bartleby, his reluctance to engage with others and lack of social skills emphasised by his gaunt looks, hesitant conversational pauses, and awkward body language. Never for a second did this feel like an actor playing a part, and so completely does McEnery immerse himself in the role that I was genuinely startled by director Friedman's assurance in his on-disc interview that the actor was in true life the polar opposite of Bartleby.

I've no doubt at all that both Melville's original story and Friedman's film were intended to be read as analogies, and both are left open for the individual reader and viewer to interpret and extrapolate from. That Friedman was able to update a text written the mid 1800s and set in America's Wall Street to late 1960s London, without major changes, is a comment on the unchanging nature of some aspects of society and work life in itself, and has kept it glumly relevant 50 years on. Is it a critique of the soulless nature of the modern office environment and work? A reflection on the disconnect between the generations? A commentary on a lack of understanding of depression and mental illness in general? A cynical view of passive resistance as ultimately self-destructive? All are feasible, and more besides. It's this, coupled with Friedman's impressively unshowy direction and the quietly excellent performances of the two leads, that make an odd but also oddly captivating and ultimately sad film like Bartleby worthy of wider awareness and appreciation.

Bartleby was restored by Powerhouse Films at Final Frame Post in London, with the original 35mm camera negative scanned at 4K, and restoration work undertaken at 2K to remove dirt and unstable frames. Framed in its original 1.85:1 aspect ratio, the resulting 1080p transfer captures the film's clean, naturalistic lighting and deliberate drab colour most impressively, with image detail crisply rendered (save for a couple of shots where the focus appears to have been just a whisper off) and a fine film grain visible throughout. As expected, there's nary a dust spot or mark to be seen. This is a really nice transfer.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack was remastered from the original 35mm optical element and is clean of blemishes and any signs of wear and in robust shape. This is a primarily dialogue-driven film, and the vocal delivery is clearly rendered, as is Roger Webb's score, which is at its best (and least dated) when used to subtly underscore the emotion of a scene.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available if needed. Unless, of course, you'd prefer not to use them…

Audio interview with Anthony Friedmann(14:31)

Audio only, perhaps, but this interview with writer-director Anthony Friedmann is a most welcome inclusion, providing as it does information of his background, his time at what was then the newly established London School of Film Technique, and how he and classmate Rodney Carr-Smith got this film adaptation of Bartleby into production. There are some interesting areas of discussion here, including whether a literary adaptation can be successfully updated or should be period-faithful, how the film was financed by a scheme that was ended by 'Thatcher', and the ways in which the film's distribution was messed up by people who distribute films for a living.

Bartleby's London (3:37)

A useful guide to the London locations featured in Bartleby, which are identified using captioned clips from the film set to music from its score. For those who know the locations, it's interesting to see how much some of them have changed.

Theatrical Trailer (1:41)

This is unusual. It's clear that those tasked with selling the film hadn't a clue how to do so in what was then the standard manner, so they kick this trailer off with the following textual scroll: "IMPORTANT ANNOUNCEMENT. Owing to the usual theme of the Pantheon Film Productions presentation BARTLEBY and the difficulty of conveying its content by conventional means, we have dispensed with an orthodox trailer so as not to spoil your enjoyment of the film." Nice try. We are then treated to shots of various characters talking about Bartleby, but only one shot in which the lad himself appears, and even then he's sitting statically some distance from the camera. The narrator then tries to sell the film as a mystery by barking, "Who is Bartleby? What is Bartleby? See it and find out!"

Image Gallery

27 screens of production stills, behind-the-scenes photos, scans of Anthony Friedman's The Genesis of Bartleby the Movie, press kit pages and Special Mention certificates from the San Sebastián International Film Festival, and a couple of posters, the first of which I want on my wall.

Script Gallery

32 screens containing scans (two page per screen) of the film's shooting script.

Beat the Bomber (16:08)

Oh, this takes me back. Made in 1975 during a period of high sectarian violence in Northern Ireland, this short information film outlines what business owners and employees should do if they discover that a bomb has been planted on their premises, as well as what to look for, what precautions to take, and what not to do. Directed by Anthony Friedmann for the Northern Ireland Distributive Industry and Catering Industry Training Boards, it delivers its messages with a blend of sober narration, clearly presented visuals, to-camera advice from unnamed individuals (one is clearly a high-up police official), documentary coverage of military deployment, and news footage of actual bombings. I'm old enough to remember this time, and while this was shot in Northern Ireland and targeted primarily at Northern Irish businesses, much of the information here was also relevant to the British mainland, which also saw its share of terrorist attacks. More than once I had to evacuate buildings due to a bomb scare, and for one of my first-year projects at film school, I wrote a short drama designed to heighten public awareness of bombings that were still taking place. This all thankfully ended with the signing of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, and that's why the Northern Ireland Protocol is so important, despite what some reckless and history-ignorant right-wing twerps try to claim.

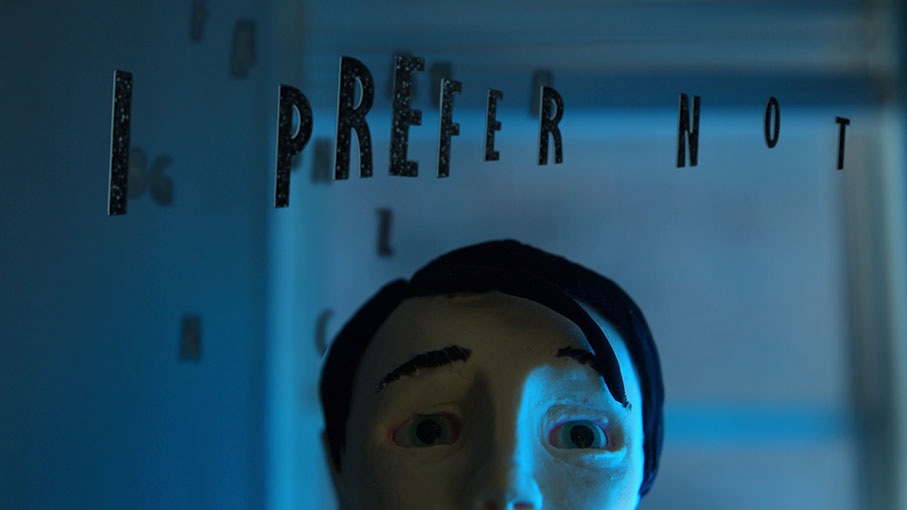

Bartleby (2017) (11:25)

A stop-motion animated version of the Melville story, directed by Kristen Kee and Laura Naylor in 2017. By compressing the story down into just 11 minutes, narrative corners inevitably had to be cut, and a substantial part of the final act is reduced to an email and a newspaper headline, but the film is nicely designed and animated, and there are some intriguing ideas at play here. Most notable of these is the decision to present dialogue visually as float-away text, its delivery accompanied by the sound office actions and machinery such as writing and printing. Modern office workers as machines, anyone? That's certainly the inference of the final shot.

Booklet

The opening essay here by freelance film writer, researcher, and film historian Jeff Billington is a detailed examination of the film, its themes, its making, and its relationship to Melville's story, and shows me up a little by covering more ground, more concisely in what feels like fewer words. Up next is a short interview with actor Paul Scofield, conducted by Sydney Edwards for the 30 September 1970 issue of Evening Standard, and an interview with writer-director Anthony Friedman by journalist Bart Mills, in which he talks about Bartleby, working with Paul Scofield, and his career to date. Following this, there are extracts from four contemporary reviews, where interesting points are made, with Helen Frizzell of the Sydney Morning Herald noting similarities to the German Kasper Hauser legend, and a single paragraph from Michael Channon's lengthy 'philosophical investigation' for Art International proving so enticing that readers are encouraged to hunt out the full article for themselves. Finally, there is a paragraph on Beat the Bomber and full credits for the Bartleby short film, together with a brief appreciation. Full credits for the main feature have been included, and the booklet is illustrated with promotional stills and artwork.

A film that is guaranteed to alienate and irritate some but that I liked a great deal. I've since read Melville's story and have gained further insight into elements that are more opaque in the film, and for me it updated well and still feels oddly relevant, particularly to those of us who have spent much of the pandemic in almost complete isolation, and are now finding it hard to reconnect with the outside world. A fine transfer and some neat special features make this an easy recommendation for those who are game.

|