| |

"We can scoff and dismiss it as the last gasp ravings of a deranged opportunist. Or we can look, unflinchingly, at Von Trier's fantastically painful mirror and acknowledge the Id within us all. Now that is scary." |

| |

Kevin Maher, The Times Online review of Antichrist |

On its theatrical release there was an unholy (pun apologies) fuss made about Antichrist's content, and it split critics pretty much straight down the middle, with some deriding it as tasteless, self-indulgent nonsense and others lauding it with equal passion (see above quote). The Cannes premiere saw several mini exoduses from the auditorium, while many of those who stayed to the end raised the roof in applause.

There are two main reasons I can see for such polemic reactions, one lies in theme, the other in style. Antichrist is a film about many things, all residing in the dark side of human nature – but one of its main themes is grief. The grief of losing a child. On this basis alone I can understand parents' unease in watching such a narrative. The other is its totally uncompromising amalgam of stylistic approaches. These will both be elaborated on now as we move onto the actual text in detail.

Scrawled blackboard text introduces the prologue; clean black and white images of a couple having sex, in slow motion, to a beautiful aria by Handel – this is all that can be heard. A toddler escapes from his cot, makes his way to an open window. The couple are oblivious, caught up in the act of love making. The child falls. Close-ups of the enigmatic expressions of emotion in all three characters, before the boy descends to his death.

I found this a truly arresting opening sequence which by the genius of Trier manages to envelope myriad emotional responses. (It is a microcosm of the whole feature in this way.) The juxtaposition of a melancholy non-diegetic classical piece of music with the heightened physical emotion of sexual expression – the tension of the boy escaping – the climax of ecstasy and tragedy simultaneously; this is the main thread of the sequence, but there are many iconographic symbols foreshadowing events to come that can only really be seen on a second viewing.

So far a von Trier follower may be thinking they're not watching one of his films at all. And it is clear from this early stage, apart from the chapter headings which has become a von Trier staple, that he is taking a departure on this picture from the realist minimalism that has underlined his style since Riget [The Kingdom].

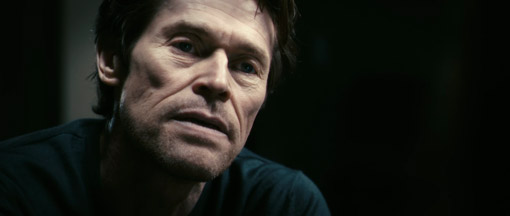

When we rejoin the grieving couple in the formally introduced 'chapter one', hints of his Dogme era are echoed in the handheld and jump-cut sequences of melancholy conversation. Willem Dafoe is the quiet strong psychiatrist husband and Charlotte Gainsbourg a shadow of a woman so consumed by grief she begins to retreat into herself. Horrific panic attacks ensue for her, so after finding out that her fears stem from the time she spent away with their son in the woods – known as Eden – when working on her thesis (on genocide, a recurring motif in the film), Dafoe initiates a trip back there to conquer her fears and appease her grief. In the transition to Eden, abstract motifs and strongly cinematic scenes become more prevalent in conveying Gainsbourg's growing anxieties about nature, although the struggle between them to regain normality is still at the heart of the picture at this point. It is here Dafoe and Gainsbourg, together with Trier's direction and Anthony Dodd Mantle's cinematography, create the most affecting portrait of a grieving couple since Nicolas Roeg's Don't Look Now. There are a few comparisons to be drawn with this film, not only the similar opening and the cosmetic fact that the protagonists consist of a quiet American man and a grief stricken English woman. A descent into desperation after changing location is present in both films, as is the characters' attempt to use sex as a way of dealing with grief, although Antichrist's brazen and explicit rawness is a far cry from Roeg's tasteful and touching sex scene. But that's the point. There is nothing touching about Trier's creation this time around. In the past he has been criticised for melodramatic sentimentality concerning his female protagonists, often having them as a single main character tackling whatever grim obstacles Lars puts in their way alone. But here Trier's male character shoulder's the burden, and, as the film goes on, shares the audiences sympathy. With the exception of the anomalous comedy The Boss Of It All, von Trier has not had a strong male protagonist for years – another return to an earlier work ethos.

As the narrative progresses and the couple (who are never named) continue their struggle, the mood becomes increasingly disquieting. Set to a soundtrack of Lynch-esque sinister rumblings (all made from natural source material recordings), the imagery of the natural landscape becomes a malevolent force and as the woman's madness deepens and Dafoe's character uncovers more clues to her anxiety, naturalism mixes with heightened symbolism to create a nightmarish and sometimes surreal state of allegory. Von Trier mixes raw documentary style footage with static camera vignettes – arresting images showing sinister natural forms, light passing over the gnarled bark of an old oak tree, a foreboding presence over the log cabin and a recurring motif connoting the lasting strength of nature. Dafoe's disturbing sightings of wild animals are powerful illustrations of constant marriage between life and death; the deer with a still born foetus protruding from its body is particularly evocative. It is at the climax of these sightings, in which a fox interrupts the chewing of its own rotting flesh to slaver 'chaos reigns' at Dafoe that provoked incredulity from certain critics. Personally I find this lapse into surrealism (another Lynch-like aspect) is both bravely experimental and quite horrifically bizarre. It jars the audience out of any safety zone they may have been retreating into, and prepared you for the sensory assault to come.

The final third of the film involves the kind of eye-wateringly brutal and unflinchingly horrific scenes of sex, violence and despair more in keeping with Asian extreme directors such as Takeshi Miike, the mood invoking the darker body horror days of David Cronenberg. Far more is it allied to these auteurs than the torture porn sub-genre of Saw and Hostel that some less imaginative or less informed critics have compared it to. The reason that it always manages to remain on a higher plateau than Eli Roth and his contemporaries is because it never strays from its strongly psychological foundation. No matter how violent or surreal the action becomes, there is always the thread of grief and loss running deep within its core, and this is in no small part down to the two mesmerising central performances. Gainsbourg draws from the darkness she reached in the wonderful The Cement Garden to create a truly powerful portrait of a woman in mental collapse that puts me in mind of Gina Rowlands' bravura performance in Cassavetes' A Woman Under The Influence, one of my all time favourite films. Willem Dafoe has no trouble equalling this with a quiet and masterful gravitas that he manages to sustain throughout his ordeal. Probably the strongest male character written by Von Trier to date.

The film ends with a monumental closing scene every bit as enigmatic as the rest of the picture in the style of previous artistic vignettes. This epilogue bookends the film with Handel's Lascia ch'io pianga, its haunting lament a fitting accompaniment to the sombre conclusion.

Antichrist was made towards the end of von Trier's chronic depression and it shows. But not in a bad way. This is not a misogynistic film (would these critics please change the record on Trier as misogynistic), but a study on the effects of grief and depression and a critique into the historical negative representation of women; a look at the follies of man underestimating the female and allying nature's power and unpredictability to femininity. It is these and more. What we also have in Antichrist is an artist exploring the very darkest corners of his psyche – as Maher mentions in my introductory quote, he is holding up a mirror to his own soul. This is Trier as Francis Bacon, as Hieronymus Bosch, as William Blake as much as he is Polanski, Roeg or Kubrick. Antichrist sees a culmination of Trier's career as an experimental director – all his previous styles are represented here, and some more to boot. The result, in my mind, is an opus of darkly magnificent standing. A film that more than stands up to his previous achievements, and one the open minded should invest time in. Have a look into Lars von Trier's mirror, but beware of what you might find staring back at you.

The 2.35:1 transfer is tricky to accurately evaluate due to the film's varied and experimental techniques and post-production grading and manipulation. Following the stylised slow-motion monochrome prologue, the depth of field is stepped down at times to a few millimetres, focussing our attention on specific areas of the frame but making judgement calls on sharpness hard to make. Adding to the difficulty is that much of the action takes place in subdued light and is shot in almost documentary fashion, while the anxiety montages have been filmed through distortion lenses. Things are a little easier in the woodland scenes and the sometimes striking tableaux imagery, but even these have been digitally manipulated. Given that the disc was released by von Trier's own production company Zentropa, I think we can safely assume that they are true to the director's intentions. Personally I was impressed with the transfer, not so much for specifics of picture detail and integrity of contrast and colour but for how correct it feels in its coveyance of mood and atmosphere and how it is able to accommodate a range of visual styles without compromising one to better showcase another. Make no mistake, though, when the camera settles and the light is right, the crisp level of detail and subtle punchiness of the contrast justify the Blu-ray transfer, and the ability to clearly distinguish detail in the ultra-wide shots of the woman's visions of her arrival in Eden really benefit from the extra resolution that high definition provides.

You can choose between Dolby Digital 5.1 and DTS-HD 5.1. Both have a lovely clarity on the opening aria, cope well with the sequences of quietly spoken dialogue, and boast the sort of tonal and volume range that you would expect of a modern digital soundtrack. It's in the deep sinister notes of foreboding that accompany the visions of Eden that the DTS-HD track gets to really flex its muscles, delivering the sort of kick that you physically feel as well as hear. The sudden shock moments are effectively startling on both tracks. There is very clear separation of sound on both tracks.

The standard trailer kicks off a rather well supplied disc.

This is followed by a good set of featurettes. Behind the Test (6.31) shows the preproduction test scenes shot to see how some of the camera and green-screen effects would work out. It's a technically interesting feature that depicts von Trier's growing experimentation with technology. The Evil of Woman (7.41) is about the research done into historical depictions of women as evil, from the occult to philosophy, with input by producer Meta Louise Foldager. Von Trier also explains his intentions in the movie regarding this theme. The Visual Style of Antichrist (15.30) concerns the different styles of cinematography used in the film, with input from von Trier's long time collaborator Anthony Dodd Mantle. Another fascinating insight into the experimental techniques used in the production. Eden – Production Design (5.09) contains locations scouting and set design footage, focusing largely on the log cabin and its location. The Three Beggars – The Animals of Antichrist (8.05) is concerned with how the animals were used in the picture and includes interesting on and off set footage of the animal handlers at work, as well as Willem Dafoe getting a bad pecking from a raven! Confessions about Anxiety (4.56) is largely von Trier talking about his own experiences of panic attacks and how it informed Gainsbourg's performance. The Make-up Effects and Props of Antichrist (8.12) shows a couple of the more grisly prosthetic effects used in Antichrist, with make-up effects and special props men Morten Jacobsen and Thomas Foldberg. The Sound and Music of Antichrist (12.59) is more up my street, showing how the sound design was done using only the recordings of organic materials with sound designer Kristian Eidnes Anderson. There is also footage of the recording of the Handel piece featuring violinist Bjarte Eikeand and his orchestral band 'barokksolistene' and Tuva Semmingsen, the mezzo soprano who sings in the haunting piece. I love how von Trier is obsessed with it not sounding too 'nice'. Chaos Reigns at the Cannes Film Festival 2009 (7.21) is the final featurette of this type and is a all too brief glimpse into Lars and co.'s trip to Cannes. It contains press conference footage of a Daily Mail dimwit demanding that Von Trier justifies his making of such a film. His response is suitably eccentric, and possibly a little arrogant!

Next there are interviews with the two characters. Charlotte Gainsbourg (6.18) is articulate in a mousy kind of a way, discussing how Trier made her feel comfortable with physically demanding and explicit scenes. Willem Dafoe (8.04) is a true gentleman, humbly expressing his delight in how he got the role and peppers the interview in admiration for Trier as a director and a writer, yet sympathetic to his mental trials of the time.

We finally come to the Commentary with the Director and Prof. Murray Smith (based local to us, at Kent University). This is a packed audio track with Smith's scholarly and methodical approach the perfect foil to Trier's ambiguity. They discuss and analyse many aspects of the film including technical and stylistic decisions and how Antichrist was influenced by many directors from Tarkovsky and Polanski to Coppola and Kubrick. The use of sound and music is also discussed and the unusually highly symbolic use of mise-en-scene Trier utilises. Smith has the habit of rambling slightly, and it would have been nice if he had given Lars a little more breathing space, as he is not the fastest of talkers! Von Trier is characteristically self-effacing and self-deprecating, although he finally admits he now finds the film 'charming '...possibly not first word I would associate with it.

A haunting, thrilling and sometimes scary journey into the primitive elements of the human condition, Antichrist may not be to everyone's taste but is a truly stunning piece of contemporary cinema in an age when originality is hard to come by. The Blu-ray package is pretty good, with the stand out feature being a very informative commentary track. Buy it, and let chaos reign for a couple of hours in the comfort of your own home.

|