'Tastemaker' |

Noun. |

A person who decides or influences what is or will become fashionable. |

A Conceivably Arrogant Foreword

I recently entered a competition. I did not win nor was I shortlisted. That's fine. If I were to write without rancour or sour grapes of any kind (yes, it may just be possible) I would say that I thought I was being invited to submit a piece of work of a certain standard and above, a 'crafted apple' if the fruit metaphor (sour or otherwise) can hold its ground; a short narrative with subtext, word-play, signposts, pay offs and strong characters. I also know that the judgement of most of these aspects in any story is inevitably wildly and frustratingly subjective. One person's Keats is another one's Tennyson. Some may not 'get' things that others will find in plain sight or perhaps regard as being too subtle or too 'on the nose' to be effective. The final arbiter of the competition was a successful author (somehow, you can't argue with success). I read one of his/her books. It was a simple and one-note 'orange' and from that moment on, I knew my 'crafted apple' was as good as pulped. I was a little frustrated. Where are those people whose judgements set standards of quality? Where are those people who push art and craft forward as exemplars of their kind? The winning entry was as much of an orange as the judge's own work (IMHO, IMAO) and that does not mean 'laughing my ass off...' You may sneer at such arrogance (I would) but it is galling to see such an overall drop in quality across the arts and crafts. Is this because we are all at it thanks to the internet? If I were to write with rancour and sour grapes, I'd probably just say this; where are the bloody tastemakers when you need them?

Whoah!

There are people who do that? What or whom did I used to think actually did this? Robots? God? A democratically elected body? The consensus of a thousand experts? You could argue that modern tastemakers are those artists and craftspeople who reveal our tastes rather than set them. H. R. Giger (R.I.P.) certainly redefined the iconography of horror. J. K. Rowling released our inner love for orphans, boarding schools and magic, from which ingredients emerged essentially beautifully crafted stories. And you have to nod to the varied but hugely influential career of a Mr. Steven Spielberg. But what if it was a real profession, tastemaker? How do you get experience for this job? Who drew the line? Who dotted the 'i's and crossed the 't's of the 'What's now 'in'' decree? Who, in short, set the bar? Welcome to the 21st century. In the art and craft of media, there're very few tastemakers out there anymore because we all have movie studios in our pockets and publishing houses on our laptops. We're all on our own. But should we be?

Yes, we all have the power to make, to produce for the tiniest fraction of what used to cost hundreds of thousands. The real power lies in the ability to propagate the product (sorry but the parlance is necessary if you want to shift some books or get eyes on your movies). The tiresome, ubiquitous mantra of the malaise of the British film industry is that we have no distributors. We are a nation of creatives with scant resources to get our work out to an audience. Well, that's just not true anymore, is it? Starting out in the media in the 80s, I had a vague but very real standard that existed swirling like smoke in my mind, one that fellow professionals would all work towards or use as a guiding line of excellence. And I don't believe I was being naïve. If you've been in any industry long enough and have an inkling of an aptitude for it, you can recognise quality almost instinctively. I've been invited to judge at film festivals and watching sixty-nine hours of hopeful contenders, you soon come to understand, with a profound exhale of deflation, Sturgeon's law... There's only ten per cent of quality in the universe... I think the science fiction writer said in a lecture given in 1951 that "...ninety percent of anything is crud."

Sturgeon had a point. The ten per cent he managed to produce sits highly on my shelves; the classic novel of human gestalt, 1953's More Than Human (I cannot praise that book highly enough); the Star Trek episodes he wrote contained the series' most enduring ideas and icons. Yes, these can be favourites locked into my mind from early exposure but the fact they are still up for debate many decades after their creation tells you there is a quality bar that these efforts have vaulted with feet to spare.

Beyond personal preference, is there a gene for recognising the essential quality of something? For example, you may dislike Pink Floyd's music but it can almost be scientifically proven that Dark Side of the Moon is one of the greatest musical recordings ever committed to disc, vinyl or otherwise. And that was in the pre-digital age of 1973. Any Steely Dan album is routinely used to test sound systems... Why? "Because they cared," said a managing director of a major sound company that I happen to know. If you ever judge your own work, chances are you are automatically setting a baseline of adequacy, a standard of OK-ness. But what if your work is so original (good or bad) that there is no line of OK-ness to judge it against? I guess that's what we call innovation (or failure, depending on most people's reaction). To quote Stephen Sondheim from his Pulitzer Prize winning musical Sunday In The Park With George, "Stop worrying if your vision is new. Let others make that decision… they usually do." And then, I heard this...

"There's less good, more bad. Because everybody's able to do whatever they want to do. The democratisation of it, fantastic. But I think my kids will suffer. They won't have the quality we had growing up because there isn't somebody there... there isn't a tastemaker involved..."

These are the words of producer Lorenzo di Bonaventura, interviewed by Keanu Reeves in the hugely relevant film vs. digital doc, Side By Side. Keanu's response was telling; an impressed or disbelieving "Wow!" I couldn't tell what inspired the 'Wow!' In an argument for the importance of tastemakers, I'd say that Bonaventura has my abiding support for producing one of my favourite fantasy pictures in the last decade, Stardust. In an argument dismissing the importance of tastemakers I have to add that the man also produced (and heaven help us, continues to produce) the Transformer movies.

The man is the very personification of cognitive dissonance, the idea of holding two contradictory ideas in one's head at the same time. But is he right? Is the overall quality of cinema diminished because we all have access to the means of production? Let's look at that from another craft's perspective.

Getting published as an author was and is, in my book (sorry), the mark of perceived quality. Someone out there (experienced or not) has decided that someone else's writing is worth investing time, effort and money into promoting. We have all implicitly accepted the 'judge' as qualified without any proof at all except for perhaps having a track record of publishing that is, successful or otherwise, more based on serendipity than strategy, public whim than surefire marketing. There are no university degrees in recognising literary merit and understanding how to (what's that awful You Tube verb, 'monetise'?) generate money to sustain both writer and publisher. The stamp of approval is a bit like Terrence, a terribly seductive one. Like the real thing, it invites the tongue (a stamp, not Terrence, although…) Ask any writer. Positive feedback launches us to the stars. No reaction or a negative one, we just want to curl up and if we're generally of sound mind, die just that little bit. That confidence emanating from a publishing company is psychologically a massive step forward whether you sign a far from lucrative deal or not. It's like putting on an Edge Of Tomorrow exo-skeleton; you feel protected, armoured. I think the relevant word is 'prestige'. If you self-publish (in the past), not only were you admitting failure with that very act, you were telling your audience "It's not really very good because no one (of any note or significance) is actually publishing me..." It's the embedded subtext whether we like it or not.

Things are changing.

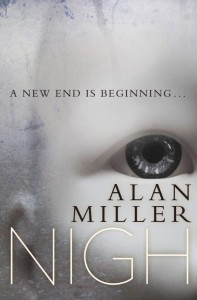

I have just finished a novel. I have created a one-minute trailer for that novel. I have rewritten the book in HTML to make the Kindle experience flawless. I have carefully formatted the Word document so Smashwords will not send it back to be re-done. I have commissioned original book cover artwork and have joined Create Space in case any of my potential readers still prefer the romantic reality of the paperback version (you have to love print-on-demand). I have even created a bespoke website to promote and support my work. Still, I look over my shoulder. The nasty taste of the phrase 'vanity publishing' still needs to be gargled and spat out. The time and energy I have expended on the work is frankly colossal and the chances of recouping that effort monetarily is as next to zero as it is mathematically possible to be. I have no PR Company behind me and the point of getting it out there is more to do with the fact that it's doing nothing sitting on hard drives in my office. There is no point in archiving creative work if it's not had a spell in the playground first. But who's stopping me? Surely there's someone out there waiting to stop me? Tastemaker, reveal thyself…

As no tastemaker, guardian of the industry or gatekeeper what-have-you has approved my work to be released to the public, what right have I to make that decision myself? I received forty-two (a significant but depressing number) rejections from publishers and agents but not one of those gatekeepers read a single sentence of my work. William Goldman's "No one knows anything," dictum works across the board in any creative endeavour. John Cleese (whose Fawlty Towers was initially rejected by the BBC) said the same thing after a lifetime's contemplation. No one knows what will work. Go back to the early 90s. You're a publisher. I have this idea about a boy wizard in a magical boarding school... Billy Bunter on broomsticks? Close the door on your way out. I know Potter was turned down a number of times. Who knew? The readers knew. Both The Hobbit and Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone were published and sold to the US respectively based on the opinions of young children who read advance copies. You cannot beat that level of enthusiasm. This is why word of mouth is the most potent marketing force. I'd love to know how to turn on that particular spigot. Oh, wait. I do. Write a hugely compelling novel, use Mailchimp to amass a mailing list and generate a subtle campaign (it's a web app a little more powerful than Mail for mail campaigns) and hope everyone in your address book forwards the link to everyone in their address books and so on until the book catches fire. For my more modest (and realistic) ambitions, it'll definitely be a waiting game. But it will feel good that the work is out there with more to come.

And still I strain to hear the disapprovers, the naysayers, those that will metaphorically kick me to the ground and by implication say "You are not good enough because only we know what can sell, what can satisfy, what can give readers a sense of confidence in a book's quality..." Some of these publishers publish appalling titles (and they must know this), moronic work in which someone has seen a gleam of potential profit. Well, the world is not wholly theirs anymore... They're dwindling in number and influence and they're thrashing at the chains of a business model that's not just an anachronism, it's a relic. If I'm lucky enough to drum up a readership that allows me time to write more then I will consider myself one of the very privileged few. Recent news tells us that the average earnings for a writer these days is more than 50% below living wage which averages out to about £24,000 per annum. The average full-time writer earns about £11,000. The fanciful notion fuelled by the Rowlings and Dan Browns of the world that if you publish a book, you're set for life, is far from any recognisable reality. Those who write for a living these days are often drowned out by those millions of bloggers (irony-aware sentence, trust me) who want to be heard but have no illusions that their shared thoughts will generate anything like an income to survive on. I'm reminded of that cliché that '...blogs are like assholes. Everyone's got one.' Or to go back to Rowling and her dissection of the publishing world in her new Cormoran Strike crime novel, The Silkworm... Author du jour, Michael Fancourt says "The whole world's writing novels but nobody's reading them." Ouch. The adults are away and the children are overrunning the playground.

It does feel a little like that scene in the original Robocop when the cops are on strike so the bad guys take advantage of the temporary anarchy. I'm not suggesting we all loot and test ridiculously powerful weapons on the streets. While I don't count the efforts of this site as anything like what you may regard as 'blogging', our reviews, like the world's blogs, still bob up and down like corks in a vast ocean, the digisea, and due to the staunchly held ethos of its founder, there will never be any ads on this site, something that still gives me a warm glow. But like those wonderfully optimistic American Samoan football players in Next Goal Wins, we have day jobs to keep financially afloat but I for one would just adore staying dry by writing for a living. Self-publishing this novel is my attempt at a subtle start of a career change. After over a decade of writing for this site out of love and enthusiasm for the things I'm writing about, I have come to the very real conclusion that this is how I want to spend my time. And the subject of tastemakers (I was actually taken aback to find the word existed) was too good to resist as I'm aiming to defy them with my novel. There are two sides to the tastemaker argument and despite my opposition to them when it comes to giving me a chance to find a readership via a self published e-book (available too in paperback!), I actually miss them in other areas of popular culture. In my past there was always a sense that there was a line of excellence, a second line of satisfactory and a third line of barely adequate. These lines were not literal but they may well have been to me, trained as I was at the BBC in the Pleistocene Era.

In broadcast TV and film not that long ago, there were some technical guidelines that had to be adhered to. There were rules on how bright you were allowed to broadcast and rules on colour and definition. It's a technical minefield and I'm pretty sure a lot of those rules are still in place having been massively revamped after the take up of HD and the R.I.P. nature of most interlaced-screening cathode ray tube TVs. But in terms of taste, talent and worthiness for want of a better word, there are no lines of quality anymore, no middle managing shop stewards pointing at their watches to make sure their members are not being taken advantage of. We are all adrift in this vast digital sea, waving and drowning. I self-publish for one simple reason; I now have the means to reach an audience despite my PR budget being lower than sweet chariots. There is no one out there to stop me. This wasn't always the case. The tastemakers started evacuating the planet quite a few years ago.

On the other hand... In the month that Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs emerged blinking bloodily into life in 1992, I cut a sequence in a television documentary of an animal being euthanised. It had led a wretched life, was continually mistreated by its human owners and the end was near. Vets had come to the sad conclusion that its wounds were irreparable and that it would be a kindness to put it out of its evident misery. I submitted my cut (the sequence almost cut itself as the narrative and profound sorrow were in place already). The Executive Producer gave it straight back to me and said "You've missed all the good bits... Put them in." What she meant were the shots that were technically unacceptable to me but which showed, with their terrible camera moves in their blurry, and badly framed way, emotion on screen. Emotion, as I should have known at that time, trumps everything else. The problem was that I had a standard below which I was not comfortable venturing. It was the first time I realised the entire film and television industry was changing. Shots had started to appear on the screen that five years earlier would not have been considered competent enough to make it to air. As the choosers of shots albeit sometimes being directed, picture editors must claim some responsibility for the alarming standard drop and general decline in the quality of content. Well, that and the state of our media-soaked world. Only last night on the BBC's Countryfile, there was a series of shots with an enormous blob (rain on the lens?) on the screen that with a tiny bit of care could have been digitally removed. But no one did because no one cares that much anymore. I remember taking an online course, the craft of finishing a programme or film to its optimal quality. Often (but not anymore) editors used to cut lesser quality source material (offline) and then someone else would copy the editor's work with the best quality shots (online). I asked my instructor what the technical line of acceptability was with TV images. He looked at me as if I'd just burped out the first line of the National Anthem. "There is none anymore," he said.

Without a rudder, a ship goes where the currents dictate. This is neither good nor bad just inconvenient if you're on the boat and desperately want to get home. We're all in the same boat now and I honestly hope you're enjoying the journey because there's no one at the wheel...

Postscript

If you want to imagine what a world is like without tastemakers or indeed, a world in which we all grow younger heading for extinction, then feel free to click here to see if my novel is to your taste... And no, I didn't come up with this article as a means to get you to my novel. This link would be much higher up if that was the case... If you enjoy it, tell everyone.

|