|

I find it hard to adequately put into words the impact that Tobe Hooper had on my generation of horror film fans. Hooper was one of a small but crucial handful of directors who changed the face of cinematic horror almost overnight, making films on low budgets that broke with all tradition and trod dangerous and thrilling new ground, and in the process dragging the horror movie out of the past and into the modern age. As horror fans, we owe these people everything. And in the space of just a couple of fateful years, they have tragically started to leave us. First went Wes Craven, whose 1972 Last House on the Left so upset the BBFC that it banned in any form in the UK until 2002 and not released uncut until 2008, 36 years after it was made. Then just a month ago we lost George Romero, whose pioneering 1968 horror classic, Night of the Living Dead, almost single-handedly gave birth to the modern zombie movie (an honour it shares with Romero's own follow-up, Dawn of the Dead).

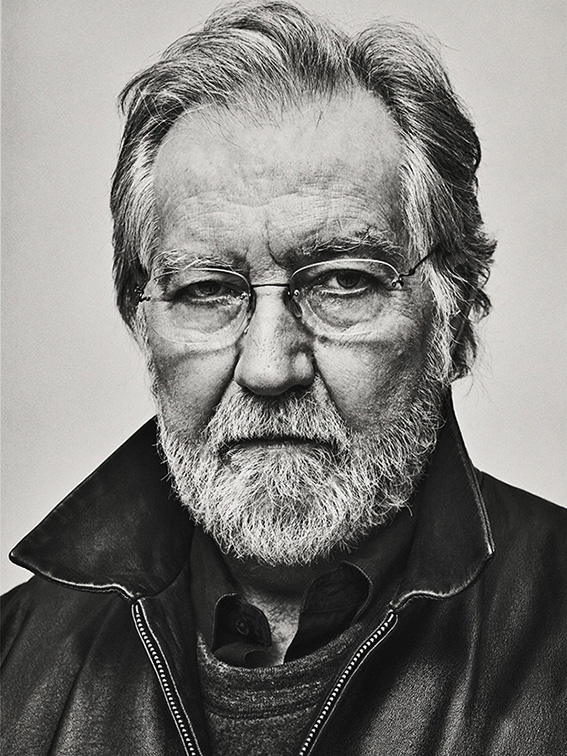

Last Sunday came the sad news that Tobe Hooper had also passed away at the unripe age of 74. A tad ironic given that it was back in 1974 that Hooper transformed the horror genre with a little film titled The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. As with Craven's breakthrough film, it was banned in the UK, except for London where it was issued a special certificate that allowed it to be screened in a slightly censored form. I was in my mid-teens back then, and while I was willing to bullshit my way into martial arts movies at the local Odeon, I lacked the self-confidence to travel up to the big city and try my luck at an unfamiliar cinema, one that in my young mind was probably run by gangsters who might beat me with rubber hoses for such a display of impudence. But everything I read about the film was telling me that it might be worth the risk. It was another three years before I made that particular journey, by when I was old enough not to have to dress up like a twerp to make myself look just a little like an adult. Despite all I'd read and all the films I'd seen since, it still left me sweating and breathless and secretly praying that it was still light outside. Even today, the sheer intensity of the film has the power to knock the unwary viewer for six – when re-watching the film on Blu-ray for the first time in some years for my review of the 40th Anniversary Edition, I was caught out by how much it still shook me. It's impact on the next generation of filmmakers and even a number of Hooper's contemporaries was also substantial. I've little doubt that it helped to shape the feel and intensity of Wes Craven's The Hills Have Eyes, Ridley Scott admitted that with Alien he wanted to make "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre of sci-fi films," and genre directors from Sam Raimi to John Carpenter have all cited it as a key influence on them. Genre writer Stephen Thrower memorably described it as "a perfect jewel of a film," and on Hooper's death, The Exorcist director William Friedkin called it as "the most terrifying film ever." Not a bad way to launch your career.

Yet this was actually Hooper's second full-length feature, and a very different film to his counterculture debut, Eggshells, which was recently restored and included as an extra feature on the Arrow Blu-ray of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. And it's really something, a fascinating work that experiments with form and content and even weaves in a supernatural subplot. It's also gorgeously shot by Hooper himself, whose first film work was as a documentary cameraman. For me, the inclusion of this film was the key reason to own Arrow's impressive disc set.

Of course, the problem with making such a ground-breaking film so early in your career is that whatever you do next, it's never going to live up to the unrealistic expectations that people will have for it. They want something as strong and as innovative and as confrontational as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and refuse to accept the idea that lightning rarely strikes in the same spot twice. And Hooper's next movie was almost the antithesis of Texas Chainsaw's terrifying realism, a work whose carefully crafted artificiality left audiences wondering just how they were actually supposed to respond to it. That's certainly what happened to me on my first viewing of Eaten Alive (aka Death Trap), despite the comforting presence of Texas Chain Saw lead screamer Marilyn Burns and Hooper's undented flair for the strange and grotesque. Coming back to it years later I found much to enjoy and admire, and over the years the film has built a small cult following of its own (you can read our review of the Blu-ray here). That's not the last time you'll be reading that phrase here.

Watch Hooper's first three features in succession and you become acutely aware of two things. First, that he is a filmmaker of rare and considerable talent, and second, that you really couldn't predict what he'd do next. As if to underline this, he then directed a TV mini-series adaptation of Stephen King's small-town vampire tale, Salem's Lot. It's no secret that this was originally intended to be a feature film directed by fellow master of horror George Romero, but circumstances stalled the project and it ended up in the hands of producer Richard Kobritz, who already worked with a young John Carpenter on his TV movie thriller, Someone's Watching Me! (aka Highrise) and would go on to produce Carpenter's own Stephen King adaptation, Christine. Originally screened in two parts on consecutive nights in the UK, Salem's Lot was a big deal for horror fans of the day, being the latest from Tobe Hooper and only the second adaptation of a Stephen King novel – his second, as it happens. Sure, we would have preferred a lead player with a little more range than David Soul (I quickly warmed to him, though he does tend to wear the same worried expression for much of the three-hour running time) and a few of the cheaper jolts are from the jump-scare horror manual. But these are minor quibbles in a work that has become a genre fan favourite, and with good reason. The screenplay, by The Friends of Eddie Coyle and Carrie screenwriter Paul Monash, is one of the smartest in modern horror, and the supporting cast is peppered with memorable turns from a range of familiar faces, including George Dzundza, Bonnie Bedelia, Lew Ayres, Elisha Cook Jr, Geoffrey Lewis, Fred Willard and a young Mark Kerwin. The jewel in the casting crown, however, is James Mason's superb performance as the vampire's human familiar, Richard Straker, oozing quiet but still menacing self-confidence and rendering every line quotable through his delicious delivery. Every time I watch the film – and I have it now on VHS, DVD and Blu-ray – he has me bouncing with glee each time he appears and particularly when he speaks, infusing even a simple word like "Chow" with layers of possible meaning and intent. The sequence in which Ralphie Glick floats outside of his brother Danny's bedroom window (and later, when Danny does likewise to his friend Mark) and attracts his attention by scratching on the glass is one that repeatedly features on lists of creepiest film sequences, and despite transforming King's more classical vampire into a Nosferatu-like monster, King himself was impressed with the result, and made a point of tweeting his satisfaction on the news of Hooper's passing.

Two years later, Hooper was back in cinemas with The Funhouse, a teens-in-peril horror that at the time got lumped in with the plethora of slasher movies that were hitting the screen in the early 1980s. Yet despite the inclusion of a number of that sub-genre's tropes, Hooper's film proved to be a lot smarter and more thoughtful than this glib attempt at compartmentalisation might suggest. I saw it at the cinema and loved it, and years later screened a painfully cropped VHS version for a couple of friends, one of whom blew loud and contemptuous raspberries as the final credits rolled, which actually put me off watching gain for a while. Coming back to the film on DVD and later Blu-ray, however, I felt my first response was fully vindicated, and the film is now highly regarded by genre fans. You can check out my review of the Blu-ray here, which includes a link to my review of the earlier DVD.

It's after this that things began to creatively stumble for Hooper, and once again I have to emphasise that I'm talking from a personal perspective here, as a number of you are going to take issue with part of this. After years making low-budget genre movies, Hooper landed what on paper sounds like a dream gig, directing a big-budget horror movie (well, big for a horror movie) for writer and producer Steven Spielberg. The 1982 Poltergeist was a critical and box-office hit, far and away the most financially successful film in Hooper's career. But what should have elevated him to A-list status and allowed him his pick of future projects ultimately became a bit of a millstone. Stories began circulating that Spielberg's role in the film was more creatively hands-on than his writer-producer role might suggest, with some even suggesting that he had taken over the directorial reigns from Hooper. Spielberg himself went public to deny these rumours, yet it was partly his own account of the shoot that started them in the first place. Subsequent comments from those who worked on the film have proved conflicting, some stating that Hooper was indeed the director, while others claiming that Spielberg was running the show. The mid-ground consensus was that it was likely a collaborative effort.

I learned of all this some while after I first saw the film, and found myself conflicted in my views. The idea that even someone of Spielberg's stature would hire a filmmaker of Hooper's skill and singular vision and then take control of the film himself seemed a little absurd, but in an odd way also made a kind of twisted sense. At the time, Spielberg had a clause in his contract with Universal that he could not direct another film whilst prepping E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, so although he was writer and producer of the film, contractually he was unable to direct it, or at least accept a director's credit. And here's the thing. Poltergeist remains to this day a hugely popular and critically acclaimed work of supernatural horror, but I never liked it. For me, it was overblown and riddled with some of the very things that made a number of Spielberg movies of the period so indigestible. And so you know the extent of my blinkered prejudice here, I'm absolutely including E.T. in that sweep. In Poltergeist, there was a little too much Spielberg and nowhere near enough Hooper. We'll probably never know for sure exactly what happened on the Poltergeist shoot, but while Spielberg's career went from strength to strength, this was to be the last big commercial and critical success of Hooper's career.

But for all that, he wasn't finished yet. As if determined to flummox those looking to predict what he would do next, Hooper then directed a music video for glam-punk rocker Billy Idol's Dancing with Myself. Even here, Hooper's energy and flair for horror imagery and the grotesque is in clear evidence, notably in the glimpses into apartments during the opening elevator trip and the recycling of props from the Funhouse shoot. You can watch the video here.

Hooper followed this with Lifeforce, the first film in a three-picture deal for the oft-maligned Cannon Films. An energetic, big budget and whacked-out tale of extra-terrestrial vampires, it was co-written by post-Alien Dan O'Bannon and drew inspiration from Nigel Kneale's classic 60s sf-horror, Quatermass and the Pit. Despite a boffo cast that includes Steve Railsback, Peter Firth, Frank Finlay, Patrick Stewart and Aubrey Morris, and special effects from Star Wars maestro John Dykstra, the film was released to largely negative reviews and failed to recoup its $25 million budget. That said, even back then it had its supporters and – in what became almost a template story for Hooper's film career – gained a sizeable cult following in the years that followed and is a personal favourite of a certain Quentin Tarantino.

Hooper's second film for Cannon, a remake of William Cameron Menzies' Invaders from Mars, was a complete misfire and the first of Hooper's critical and box-office flops that has yet to find enough vocal fans to constitute even a small cult. Certainly, it's the one Hooper film that I struggle to find anything positive to say about, and as a fan of the original, this remake stings me as sharply as Carpenter's retooling of Village of the Damned.

Hooper's third Cannon film was far and away the most anticipated of his career, being a sequel to his career-defining breakthrough film. But in that way Hooper had of confounding expectations, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 ("Chainsaw" would be one word from this point onwards) threw the gut-clenching realism of its predecessor out of the window and opted instead for brightly coloured and over-the-top black comedy. The first time I saw it 9in an admittedly cut form) I was left genuinely slack-jawed in disbelief, and although the film has become a genuine cult favourite since, I still don't know how to react to the damned thing. You can check out Gort's review of Arrow's brilliant dual format release of the film – which also includes Hooper's debut feature Eggshells – here.

It's about here that Hooper's career as a feature film director stumbled and fell. From this point on he would work primarily in television, helming individual episodes from series such as Amazing Stories, Freddy's Nightmares, Tales from the Crypt, Dark Skies and Masters of Horror. Intermittently he would direct the odd feature, a couple of which – Spontaneous Combustion (1990) and The Mangler (1995) come to mind – have noteworthy components, but his late-career work is not what he is, nor indeed should be, remembered for. The simple fact is that had Hooper only directed The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, then he would still be rightly revered as a Horror God. With that one film, he changed the course of modern horror, and did it with such skill and such technical proficiency that even today you don't have to make allowances for its age to appreciate its brilliance and be scared shitless by it. But Hooper gave us so much more, and continued to work in the genre with which he made his name and along the way delivered a handful of still treasured treats. His standing within the horror community ensured that when the news of his death was announced, it was his fellow genre practitioners who were first to offer their tributes. All were touching and heartfelt, but it was author and occasional director Clive Barker who was the most poetic when he tweeted, "The chainsaw is now quiet, but it will forever be heard." Indeed.

RIP Tobe Hooper.

|