|

The following two pieces were written independently of each other and in tandem by two very like-minded and similarly enthusiastic individuals. Please forgive any repetition or crossover.

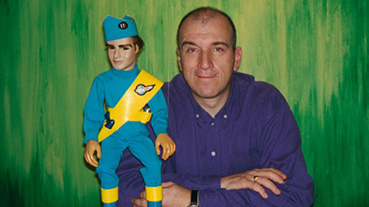

'I thought that the people with the money would say, "Christ, this guy's making

good puppet films here, we ought to give him some live action!" Instead of

that they said, "Doesn't he make good puppet films, let's give him some more

puppet films." So I became trapped. And all the way along the line I hated

the bloody things. But when I look back now at shows like Thunderbirds

and Captain Scarlet I'm at long last really quite proud of them." |

|

And so he should be. It's impossible for me not to be both constrained and bolstered by my own childhood experiences but I will make the relatively bold statement that in my opinion, no one person's work in the media has so wonderfully defined an era and inspired a whole generation of children as deeply as Gerry Anderson. After my son grew out of his own Thunderbird models (the classic originals of course, nothing from the execrable 2005 feature), they became my own cherished 'ornaments' so tightly entwined are my memories of the amazing craft and the feelings they evoke. They now sit in my den making me smile forty-five years after the show's creation. How's that for shaping childhoods? Anderson and nearly all his shows affected me in quite profound ways. From the dizzying delight of having a Thunderbird pilot with not only my name but also one with my father's to Joe 90's haircut being slavishly copied, I was Anderson's perfect demographic; a boy in love with adventure and with precious few opportunities to go on one. Let me start with a very personal and true story.

Many years ago, in the late 80s, I did a job for someone for free. It was quite a tough job relatively speaking and took a while. As a thank you the producer convinced the production company to send me to New York for a week's holiday. I was so bowled over by the generosity I wrote the producer a letter. Many years after the event she still claimed to know exactly where that letter was. It compared my current Manhattan-bound joy with a moment of perfect happiness that only a satisfied child can conceive, one unencumbered by knowledge of the outside world's suffering and injustice. It was simply this – and I know how small it sounds but trust me on this, it was everything; a Christmas day in the mid to late 60s. On that morning I was given the greatest toy my heart had ached for, a modest but brilliant Scalectrix set. It came from a Santa that resolutely existed, no question. But here's the topper. With just three TV stations to choose from and no way to record anything, ITV had scheduled a Gerry Anderson triple bill that afternoon (the details of which have leaked from my memory, but Thunderbirds was in there). What I do remember with startling clarity is a transcendent happiness, the idea that the world could not possibly get better than this. In a melancholic way, I was probably right, innocent as I was. If I'd realized this at the time I don't think I would have got up on Boxing Day...

So, I'm offering a capricious chronology of Anderson influenced memories and thinking about the following has convinced me even more that Gerry may have been significantly more influential than I thought...

Twizzle

This unsophisticated and faintly disturbing puppet that could 'twizzle' (aka elongate) its arms and legs was my introduction to Gerry Anderson though I didn't know his name at that time. This was Anderson cutting his teeth in TV production and direction. Let's ramp up the sophistication by about two percent and miss out Torchy The Battery Boy simply because I have no memory of that one at all.

Four Feather Falls

The pre-cursor to Little Britain, Anderson's next puppet show was a fantasy western of all things co-created by the man who did more to increase the Anderson effect than any other, composer Barry Gray. The Little Britain comparison is quite sound. Both shows did the same thing, time and time again with a small variation. In Sheriff Tex Tucker's case, his magic feathers caused his holsters to swivel to fire at enemies even while his hands were up in submission. Every week. Classic!

Supercar & Fireball XL5

All hail 'Supermarionation', a ludicrous, made up title which essentially meant 'puppets!', introduced here in the adventures of a super car to be followed by those of clean cut American heroes aboard the space ship Fireball XL5 (the designation of the ship coming from the brand name of an oil available at the time, Castrol XL5). I don't remember the sexual tension between Steve Zodiac and Doctor Venus (Venus, I ask you) but then I was about 5 years old. But then if sexual tension was your goal, look no further than...

Stingray

Being the support to the main act, Stingray, the futuristic adventures of James Garner and Brigitte Bardot – ahem, Troy Tempest and Marina, in a powerful and sleek submarine, boasts one of the greatest main themes of any TV show. Ever. The opening sequence of each episode is almost unbearably exciting. "Anything can happen in the next half hour..." So as a child I moved houses a lot. I know, I need to work on my segues. On our way to our new dwelling, I suddenly remembered that I'd left my Stingray model in our old bathroom. And this, folks, is when I really grew up... My parents refused to turn back and pick it up. They say you only grow up when your parents refuse to drive back to a house they no longer own to pick up your favourite toy... Or something like that. Now this is going to sound even crazier. I have a sixteen year old and still, by some profound, deep seated emotional need, there is a model Stingray sat on top of the bathroom cabinet and it's not going anywhere while I live here. I just learned that my son recently offered it up in a car boot sale. Oh. He's sure he didn't sell it so I know what I'm doing in the attic tomorrow morning... I'm starting to sound deranged but I assure you this is all true. I certainly remember the shows with great affection but we have to move to the next Anderson production to feel the crushing but welcoming bite of his influence. It all really started with... (drum roll)... the one and only...

Thunderbirds

The only way a child of the 60s could re-experience anything was via 45rpm records (singles) at the exciting maximum storage of about 6 minutes of audio and that was playing both sides. Some genius suggested putting a Thunderbirds adventure on a slower 33rpm single and editing it in such a way (with Scott Tracy himself narrating) that you could recreate the adventure in your imagination in twenty-one minutes. I had one of these records and still, to my own astonishment, can quote from it liberally... "Fireflash, lift port wing, LIFT PORT WING!!!"

Gerry Anderson was no commercial slouch. In the US (the place cool things came from in those days), the Mercury astronaut program was in full swing. I was lucky enough to work on the movie about that program, The Right Stuff, and the Thunderbirds nods came in thick and fast. All the Tracy brothers are named after astronauts from that program. They all sported US accents. The Tracy patriarch had walked on the moon, something Neil Armstrong was to do three years after the show finished its second and final series. More importantly, Anderson recognized that young boys liked explosions and young girls liked women in powerful roles. Inspired by a German mining disaster, International Rescue was created – in other words, you could have action, suspense and explosions but all in the calling of saving and not extinguishing lives. Genius. Lady Penelope, of course, was created to inflame young girls' imaginations. No demographic left behind.

But what really struck me in the era of not being able to record anything was the delirious and wonderful repetition of the launch cycles of both Thunderbirds One and Two. It was a rare, sofa-dropping treat to see Alan take the helm of TB3. The music was perfect, honed so by the glow of nostalgia, the action perfect despite the visible wires, the joy so unconfined that I am now listening to the cues that pushed, pulled and dropped Scott and Virgil into their cockpits and I'm right back in that 60s front room. As my Ren and Stimpy T shirt proclaims under a thick jumper, "Happy, happy. Joy, joy!" Don't get me started on the design of the craft. One of the happiest memories of family life is settling down to an episode and guessing with my father what number pod would Thunderbird Two descend on to in this episode. It never occurred to me that the pods were not spaced apart enough that Virgil's green behemoth could settle on it without breaking its curiously backward directed wings. I adored Thunderbird Two, still do. All of this, of course, is sugar sweet memory trapped in amber but I defy anyone who lived through that time to prove that Anderson's effect on my generation was nothing but startling. It seems incomprehensible to me now that both Thunderbirds movies (made at the height of its television popularity) tanked at the box office. If it's possible to move beyond Thunderbirds, Anderson's signature dish so to speak, then let's move on to the more realistic puppet head shapes featured in DUM DUM DUM, DUM-DUM-DUM-DUM...

Just a slight detour before we get to Mr. Indestructible... I cannot stress enough the power and influence one of Gerry's constant collaborators had over the series. His contribution glued all the parts together. I'm not talking about Derek Meddings' wonderful special effects that inspired in me a burning interest in the subject that is still very strong. No, my vote for Gerry's most important creative colleague goes to Barry Gray, the composer whose work on most of Gerry's work was superlative.

Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons

Anticipating the ground-breaking, scene changing, editorial style of Easy Rider by at least a year, Captain Scarlet was an odd bird whichever way you sliced it. The titular hero belonged to a security organisation based in the clouds on an aircraft carrier recently aped in Joss Whedon's Avengers, known as (duh) Cloud Base. The head of Spectrum (the good guys) is Colonel White and in the first episode, the agent turned to evil is (c'mon, a guess is hardly required) Captain Black. Scarlet and Black face off in a futuristic car park in episode one and in a turn of narrative Whedon himself would applaud, the hero is killed off. What a way to start. We then find out that the alien Martians (known as the Mysterons) who can resurrect dead people and rebuild blasted apart buildings mistakenly transferred this power to Scarlet. So let's think. He can cheerfully suffer agonizing pain of death every week but it's OK because he's just brought back to life. I always wondered what it was like to suffer like that. The end credits revelled in the hero's suffering to the point of silliness. Here is the hero squished by two walls of horrific spikes, falling off a cliff, weighted to drown faced by sharks, inundated with heavy boxes... Christ. I guess he's the ultimate hero, dying a weekly death and being brave enough to face the pain. But what I really loved about Scarlet and his ilk were the hats.

And in the late sixties they were commercially available. Could my family find them? No. Torture. My aunt actually attempted to knit one so furious was my wrath at not being able to find one. They were biscuit tin shaped, coloured according to the character (there were no Captain Pinks as far as I could remember) and had a small radio/receiver that would drop down on a wire in front of the wearer's lips and then go back up to the brim of the hat. I had to have one. I did eventually find and buy one only to have the radio get stuck in the down position and during that time on my summer holidays I was bitten by a chicken. Talk about nadir. Next, the kid in the revolving chocolate orange with a mad dad.

Joe 90

So this was it. This was Gerry's earnest attempt to rob his audience of any individuality. Everyone my age would have killed their grandmothers to be Joe 90. His father, Mac, is a famous inventor and has discovered a way of storing the engrams of proficient experts and can transfer them to his son via the glasses he wears. So Joe becomes the World Intelligence Network's most special agent after his own father's furious protests. An eleven-year-old boy as a secret agent? The end credits featured a schoolboy's futuristic attaché case full of pencils, compasses and school stuff but in hidden compartments (oh, joy) a gun, a silencer, a badge of identity and a radio. I also loved the idea of ID – flash that and you're walking through any cordon. I wanted that briefcase. I even styled my hair and parting on Joe's own mop. Come on. My hero was a eight inch puppet but the unsung wonder of this ultimate wish fulfillment show was another piece of tech – Mac's car. There was something insane about that design, something insane that made it perfect...

Side Note: I love the work of Joss Whedon. Any visitor to this site will have picked that up but despite having visited the sets in L.A., his latest TV show left me scratching my head. Wasn't Dollhouse just Joe 90 with tits? I do not make this remark lightly as I fully believe there is a lot more to Dollhouse than this throwaway remark implies but Anderson was there again, at the forefront of creative thinking – people able to be other people by dint of technology.

He then went off and made a show I've never seen, The Secret Service starring the acquired taste of Stanley Unwin. I used to read about it in the associated comics but it was never aired at times I was able to see it. However, Countdown, the comic had started to feature Gerry's next series, live action no less. I built up an absurd anticipation as it was broadcast but not in my neck of the woods. When ITV in South Wales finally picked it up over a year after its original transmission, they shoved it on at 11pm on a Friday evening, effectively cutting it off from its core audience. My parents were so sorry for me that they used to set the alarm, wake me up and sit me bleary eyed in front of the TV...

UFO

From the first moments of UFO I was a SHADO junkie. I adored the production design (it was all set in 1980, the far flung future) and sometimes featured an actress whom I came to regard as a rather special creature (I was growing up!), Gabrielle Drake. Unknown to me then, she was singer/songwriter Nick Drake's sister but the part in UFO did her no female empowerment favours but I was smitten. The show was about a secret establishment under a film studio – Supreme Headquarters Alien Defence Organisation, (SHADO). They monitored hostile UFOs and their organ-stealing humanoid alien occupants and if they couldn't shoot them down via Interceptors at Moonbase, they'd send submarine rockets after them and Mobiles, another design I just thought was genius. There was an attempt at telling some very strange stories and I remember them all specifically even the terrible (to me at that age) Confetti Check AOK that featured no hardware, no UFOs and was just a long winded way of saying that men in charge of secret extraterrestrial battling organisations are as prone to horrible accidents as anyone else. Bored now. But on the whole, I just dived in and rarely came up for green liquid air.

Although Gerry went on to make The Protectors (a live action spy thing), a show that never caught fire with me and Space 1999 (which blew it big time in its awful second season), I was growing up and so growing away from children's TV. At that age I had no idea just how profound Gerry Anderson's imagination had impacted my own. At over 50, I do now. Thunderbirds are gone... but, it seems, there's not a hope in hell of ever forgetting them. Bless you, Gerry Anderson.

A good few years ago, having abandoned a film industry career not that long after I'd begun it for a combination of personal and professional reasons, I was working in a media support post at a further education college. And while it wasn't the sort of job I had originally envisioned myself doing, it was proving a lot more satisfying than I would once have expected. One day a new member of staff dropped into my office to ask for my help on a video related matter. His name was Mike Trim, and he was there to teach an art course whose students had yet to discover how lucky they were. We got on well from the moment we met, in part because Mike is such a genuinely lovely and knowledgeable guy. In the course of that first meeting the conversation somehow got around to how I had landed in my present job, and I gave him my usual vague story about my premature departure from the film business, only hinting at reasons I've always preferred to keep private. To my complete surprise, he not only understood, but revealed that he too had previously worked in film and had made the decision to leave for similar reasons. It's when we compared stories that I became aware of the gaping chasm between my own industry experience and that of my visitor. I had been a runner, a camera team clapper-loader, and an assistant to the props master (which was a lot more fun than you might imagine) on a handful of commercials and independent films; Mike had spent a good part of his long career building models and designing vehicles and sets for Gerry Anderson's Century 21 Productions as part of a team headed by Derek Meddings. And if those names ring no bells, then your childhood was clearly very different from mine.

If I were forced to list the five most influential media figures of my pre-formative years, then Gerry Anderson may well occupy the top slot. His work absolutely dominated my childhood, preceding and actually eclipsing Bruce Lee, who single-handedly shaped my early teens. Anderson was, as you should well know by this point in the article, the creator of such iconic TV series as Stingray, Thunderbirds, Joe 90, Captain Scarlet and UFO. All but the last of those featured a cast of marionettes, ones with personalities so distinct and memorable that most of us never knew the names of the actors who voiced them, in spite of their commendable work elsewhere. It was many years after Captain Scarlet first aired before I realised that the titular Captain was voiced by Francis Matthews, and that the voice of his colleague Captain Blue was provided by Ed Bishop, the star of Anderson's later UFO. This focus on character over performer is brought home in the opening credits of Stingray, which announce that the star of this particular show isn't voice actor Don Mason, but James Garner-faced marionette Troy Tempest. In my innocent younger days, I could almost have believed Troy had his own agent and would go on to star in other shows and films.

When I was a kid, Anderson's Century 21 shows were far and away the best thing on TV, and for us impressionable young lads, they were much more than that. I was too young for many memories of watching Stingray as a small child to have lingered on to adulthood, but a few key components (probably from re-runs) haunted me nonetheless: the sinister Titan and his bubble-voiced minions; their torpedo-firing piranha-fish submarine, and the way its jaw flapped helplessly after critical damage; the authoritative Commander Shore and his mobile hover-chair; the whirring sound Stingray made as it barrelled through the water; the Peter Lorre-esque enemy Agent X-20, whose living room could be transformed into a bewildering collection of Bond villain electronics and communication equipment at the flick of a switch. We loved this as kids, and wanted more than anything for our bedrooms to be likewise equipped, to be able to press a button and have tables flip over to reveal radios and tape recorders that we had no real use for. This is something Anderson and his brilliant team of designers and model-makers really tapped into, creating logic-defying technology that made complete and glorious sense to children and the young at heart. This was technology you wanted to believe existed because, more than anything else, you wanted to play with it.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in Anderson's crowning achievement, Thunderbirds, the show that unquestionably had the biggest impact on my childhood bar none, despite stiff competition from Dr. Who and the original Batman. Take a step back and almost nothing in Thunderbirds made sense. The base of operations for International Rescue was a technologically astonishing island base whose location and existence is a closely guarded secret. But who built it? Who maintains it? And on the occasions that the Thunderbird craft take damage, who is it that repairs and rebuilds them? And what of the bulbous Thunderbird 2? We all loved the way the palm trees bend over to allow it to trundle its way to the launch pad, but why didn't they just build the roadway a little bit wider? And that series of elaborate chutes to transport Virgil Tracy into the cockpit probably takes longer than just having him walk there. But in Gerry Anderson productions, people never walked if there was a cool mechanical method of transporting them instead (that they did this because ity was so hard to make the puppets walk convincingly is by the by). Did we care? Did we hell. Every single young boy I knew wanted just that Thunderbird 2 chute system in their own house. It looked brilliant. So brilliant, in fact, that it gave Virgil his only real edge over young hotshot Scott, whose trip to Thunderbird 1 was done standing up on what looked a bit too much like a regular elevator.

For some reason I always got a particular thrill with if the disaster was underwater, as that meant Thunderbird 4 would be needed, and I loved that little yellow submarine to bits. This, of course, was one of a whole number of ingenious and brilliantly designed small craft that could be carried in the belly of Thunderbird 2 and its interchangeable pods. Yet the two non-Thunderbird machines that made the strongest long-term impression did not belong to the Tracy family at all. Can there be a series fan anywhere who does not remember the Sidewinder and the Crablogger? Hell, I can even hum you the Sidewinder music.

Ah, the music. I don't say this lightly, but as far as I'm concerned, Barry Gray was a composer whose talent bordered on genius. The main theme of Thunderbirds remains instantly recognisable 47 years after the show was originally broadcast, it's inspirational nature winningly demonstrated in the cult TV series Spaced, when the military-obsessed Mike convinces introspective Brian to help him take action by playing him a tape of this very music. And I'm happy to go on record as stating that as far as I'm concerned, the title sequence of Stingray ("Stand by for action!"), with its action-packed visuals and brilliant, tribal-drummed theme, remains to this day my all-time favourite opening in the history of television. For the record, the Emma Peel colour titles from The Avengers come second. Thunderbirds is a close third (and UFO is fourth).

More than any other Anderson production, Thunderbirds was an ensemble piece in which no one character dominated, allowing us to form our own personal alliances. But with Scott and Virgil featuring big in just about every episode, it did become a bit of a two-horse race, and with Virgil having the demeanour of a sensible older brother, Scott emerged as a favourite by default. The younger Alan was a touch too bratty at times (though he did have a thing for oriental Tin-Tin, the only woman of child-bearing age on an island populated by strapping young men), and poor old John seemed to spend most of his life alone on Thunderbird 5, the family's orbiting space station (also somehow constructed and launched in secret). But I did like Gordon, who delivered every line like he was popping amphetamines and who got to pilot Thunderbird 4.

There were so many great episodes, but two haunted me throughout my childhood and teenage years. Move and You're Dead saw Alan and Grandma standing on a bridge in blazing heat, unable to move without triggering a bomb. This terrified me as a kid. That's how good this show was – I could emotionally connect with a pair of marionettes and share their terror and fear for their increasing exhaustion. The Uninvited, meanwhile, saw Thunderbird 1 shot down in the desert and Scott find himself in a pyramid kitted out as a technologically advanced alien operations base. My fascination with all things ancient Egyptian aside, the idea that a mighty Thunderbird could be brought down by hostile forces was genuinely alarming for this young devotee.

My relationship with Captain Scarlet was not quite as all-encompassing, but I still thrilled at its dark tone, its super-creepy introduction of Captain Black, and the deep reverberating boom of the Mysteron voices. As a kid I spent a little too much time sticking card over torches to try and make those dual rings of light that brought the dead back to life as Mysteron agents, unable in my ignorance of the manner in which light travels and falls to make them as sharp as they appeared in the series. Captain Scarlet also had Cloudbase and the Angel Interceptors, beautifully designed attack aircraft manned by glamorous fashion models, and the first Airfix model I ever built of a craft from a Gerry Anderson show. I was in awe of a friend who had the Dinky Toy models of all three of the cars from the series, each of which are now collector's items.

For me, Joe 90 was all about the gear. The titular child didn't interest me much, but his equipment did. One of the wealthier kids at school actually had a toy version of his kitted out attaché case. Oh how I envied him. Once again my friend had the cars, at least one of which was a Mike Trim creation. I know that because when he told me he designed Sam's car I got all enthusiastic about it, only to have him point out that the car I was talking about actually belonged to Mac. Oops.

It was UFO that came closest to having the same impact my childhood as Thunderbirds. This was Anderson's first stab at a live action series, and I remember some hostile commentator at the time suggesting that the performances were about as expressive as those delivered by the Thunderbirds marionettes, which even at the time we knew was balderdash. For this space-race and science fiction enraptured teenager, UFO had everything: a beautifully edited opening sequence; a secret organisation of conspiracy theory size; a moon base run by beautiful women with shiny purple hair (like Camus, I was in love with Gabrielle Drake); flying, missile-firing Space Interceptors; a submarine whose front cabin was a detachable jet fighter; the Space Intruder Detector, aka SID (one of Mike's most striking creations); humanoid aliens who breathe liquid (which was the basis for one of the series most tensely handled scenes, one reproduced in The Abyss many years later); and possibly the best UFO craft I've ever seen in a film or TV series. These were brilliantly simple and facelessly menacing craft whose sound alone would always send shivers up my spine. Glimpsed briefly through trees from the window of a moving car, as it was in at least one episode, it also felt scarily realistic.

UFO also appeared at a time when I was discovering that I had a modicum of artistic talent, and I spent far too much of my spare time drawing the craft from the show, aided immeasurably by the UFO strip in Countdown, the comic of choice myself and my friends in our early teens. Once again Dinky were on the case with a die cast model of the Interceptor (with missile firing action!), though for some reason was coloured gold rather than the white of the series. As with so many of its Dinky/Anderson predecessors, I knew someone who had one, but never owned one myself.

In common with my writing partner, it's with Space 1999 that my love affair with Anderson's TV output started to wane. I never bought into these guys as an authentic crew, and the dramas lacked the tension and conspiratorial intrigue of the best UFO episodes (I still built an Airfix model of the Hawk spaceship). It matters not. Anderson's back-catalogue of superlative television is so thrillingly rich, and its impact on my early life so positive, that I have nothing but great memories of everything he created. So here's to Troy Tempest, Phones, Commander Shore, Atlanta, Marina, Jeff, Scott, Virgil, Alan, Gordon and John Tracy, Brains, Kyrano, Tin-Tin, The Hood ("excellent!"), Captains Scarlet, Blue and Black, Symphony, Rhapsody, Destiny, Melody and Harmony Angel, Joe and Ian McClaine, Sam Loover, Shane Weston, Ed Straker, Paul Foster, Alec Freeman, Gay Ellis, SID, Videcolor, Supermarionation, and most of all to Gerry Anderson and his wonderful, insanely talented team of collaborators. Treasure them and their legacy. Between them they created television the like of which we will never see again.

You can get a look at some of Mike Trim's artwork on his website here. And yes, he is the one who created that iconic cover artwork for Jeff Wayne's massive selling War of the Worlds album.

|