|

I long ago lost my copy of the second of David Niven's joyously entertaining autobiographies, Bring on the Empty Horses, and have been scouring second-hand bookshops for some years now in the hope of stumbling across a replacement copy. I bring this up here because of a quote I want to use that I cannot reproduce verbatim without assistance from the book in which it appeared, so you'll have to forgive any time-induced inaccuracies in what follows. Niven, I seem to recall, was at a party at the house of his friend Noël Coward and was glumly reflecting on a series of recent bereavements. When Coward asked him what was wrong, he told him that he appeared to have reached that stage in his life when many of his friends were dying. In a response that was perhaps typical of one of our most celebrated wits, Coward responded, "Frankly dear boy, I'm surprised that any of mine make it through dinner."

I'm not quite that old yet. I've lost a number of people who were close to me, but in each case the death was untimely and premature. Several of them should have outlived me. But I have reached the age where the public figures who shaped my youth are steadily and sadly diminishing in number. The losses are not personal in the same way the death of a relative of friend would be, but these people helped to define me as the person that I am today, and without realising made my teenage years and early 20s a little more tolerable and intermittently thrilling. They were the nearest I had to what others call heroes.

Camus and I are of a similar age (he's younger, but not by as much as he'd prefer, I'd imagine), and in the past couple of years I've lost count of the number of "Oh you have to be kidding!" emails that have been passed between us on hearing the news that another of the figures whose work made us into the film fans that we are had passed away. Occasionally we felt compelled to write a few words about why they meant so much to us and post them on this site. Too often we simply shook our heads in sad disbelief and poured ourselves another consolatory drink.

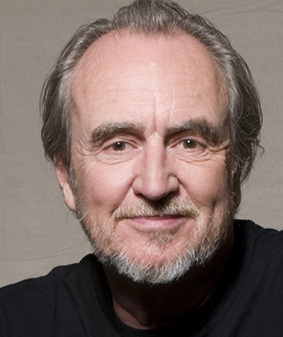

Given that this has happened so often of late, I can't quite fathom why the news that horror maestro Wes Craven had died came as such a shock. When I sat and thought about it this wet August bank holiday afternoon I had an odd realisation – it was because it never for a second occurred to me that someone like Wes Craven would die. I know that makes no sense, but the more I thought about it, the more convinced I was that peculiar delusion was behind my sense of startled disbelief. Had I been aware of his illness then maybe I'd have been more prepared, but I was not. And I wasn't alone in my reaction. The first email that landed in my inbox this morning was from Camus, and it consisted solely of the following message: "Wes! Nooooooooooooo….."

Wes Craven was one of a handful of American directors who had a serious impact on my youth. Many will cite his 1972 The Last House on the Left as the film that defined his career as one of America's most important horror directors, and while it was unquestionably a hugely influential and game-changing career-launcher, in the UK back in the pre-internet and pre-home video days you just couldn't see it. It was refused a certificate by the BBFC, and few of us were even aware of its existence until the early 1980s, when a loophole in the law allowed distributors to release films uncertified on video cassette, and for a short while the film was freely available in its uncut form. It wasn't out there long before it fell victim to the 1984 Video Recordings Act and found itself on the now notorious "video nasties" list. It remained a banned film for almost two decades, and even then was only released after 31 seconds of cuts were enforced.

My first encounter with the work of Wes Craven was his 1977 The Hills Have Eyes. This was a film that had me bristling with excitement from its opening minutes, not through any fast-paced action or levitating shocks, but because it had the sort of atmosphere and sense of primitive threat that only American indie horrors of the 70s seemed able to generate. The film that unfolded was as smart as it was visceral, underscoring the tension and violence with a fascinating exploration of opposing concepts of the family unit. My review of the film for the university magazine was one of the first I ever wrote (at least that was read by others) and did not go down well with one of my film lecturers. "Was it you that wrote the review of that awful film, The Hills Have Eyes?" He asked me. "Yes it was," I assured him. "It was the best film I've seen since The Texas Chain Saw Massacre." The look of disgust that crossed his face was so acute that I'm surprised I wasn't promptly booted off the course.

A few years later I travelled up to Manchester to spend a few days with a girlfriend I should have broken up with about six months earlier. If that sounds like I was being a typically heartless male git, know that she felt exactly the same about me, but we still got on well and neither of us had summoned up the necessary courage to point out what was getting rather obvious to both of us by now. During my visit we finally addressed the elephant in the room and called it quits. The effect was genuinely liberating. As I headed back down south I stopped off in London and called my closest friend – who lived on the city outskirts and was currently unemployed – and told him to haul his arse up to Leicester Square and I'd pay for a couple of cinema tickets. While in Manchester I'd passed some down time reading the latest issue of Time Out (I still have this copy), and they'd been enthusing wildly about this new film from the man who a few years ago had given us The Hills Have Eyes. The film in question was A Nightmare on Elm Street. Best breakup movie ever. All these years later, after so many sequels and increasingly jokey spin-off's, it's a little too easy to forget just what a thrillingly original and scary film this was when it first exploded on an unsuspecting public. We were left reeling and stumbled straight into the nearest pub for three hours of drinking a post-film discussion. It remains one of my most fondly (and vividly) remembered cinema visits.

Flip forward a few years and Craven struck horror gold all over again with the genre phenomenon that was Scream. I was given a foretaste of just how much of an impact this film was to make by a student I was working with at the time of its release, an ardent horror fan with an eye and ear for quality who had been to an advance screening of Craven's film and was talking about it as if he had witnessed the second coming. That its memory eventually became just a little tarnished by the decreasing quality of the sequels – a fate that also befell A Nightmare on Elm Street – should not in any way detract from what Craven and screenwriter Kevin Williamson achieved here and the surge of encouragement it gave to those of us who feared that the genre's best days were far behind it.

It's doubtless those game-changers for which Craven will be most commonly remembered, but there are a number of other less widely trumpeted gems for which we genre fans will forever worship at the temple bearing his name. His 1981 Deadly Blessing may have been compromised by a studio enforced ending, but it inventively reworked the key theme of opposing family units from The Hills Have Eyes, had Ernest Ernest Borgnine as a fire-and-brimstone Amish patriarch and introduced the world to a fresh-faced young actress named Sharon Stone. The 1982 Swamp Thing is a lot more fun than some give it credit for and has a cast that includes personal favourites Louis Jordan, Adrienne Barbeau and Ray Wise. The 1988 The Serpent and the Rainbow is an tightly constructed, unsettlingly plausible and sometimes frightening tale ifeaturing Bill Pullman as an American anthropologist who falls victim to Haitian black magic, and was actress Cathy Tyson's follow-up to her striking debut role in Mona Lisa. New Nightmare was a post-modernist gamble that brought the Nightmare on Elm Street series to an appropriately and unexpectedly tense and effective conclusion, while The People Under the Stairs is not just a wonderfully demented thriller in its own right, it's also one of the smartest and most socially conscious political horror films of the modern age.

Craven was also an excellent interviewee and, like his contemporaries David Cronenberg, John Carpenter and Clive Barker, a fiercely intelligent ambassador for the genre. Having earned his Masters Degree in Philosophy and Writing from Johns Hopkins University, he briefly taught English at Pennsylvania's Westminster College before making the leap into film production. It's a little known fact that he started in porn, apparently working under a variety of pseudonyms, before the commercial success and critical success of the low-budget The Last House on the Left transformed the path of his career forever. Wes was one of the true horror greats, but a simpler and perhaps more suitable epitaph can be found on the home page of his official web site, wescraven.com, which carries the words, "Wes Craven, Filmmaker." Thanks Wes. Seriously, man, you made a real difference.

|