"I love independent filmmaking. I don't agree

with a lot of it, but that's the point." |

Indy star, Gena Rowlands |

In 2003, I bit the bullet and made a feature film. This had been on my 'To Do' list for about four decades. It was shot in a month with a talented cast and crew as willing volunteers (to whom I will always be hugely grateful – you know who you are). I'd saved like mad to afford it and was supported during its production by an inspiring and tolerant partner. Post-production (usually my forte) struck a massive – if metaphorical – iceberg and the project was temporarily halted by dramatically failing technology. It was a frustration so keenly felt that after a violent metallic dismemberment, I performed a wake and cremation for the offending hard drive. Keeping busy and earning a living prevented me from hunkering down and getting the film finished. At last, years on, I found the time and with renewed enthusiasm and help from some extraordinary people in Amsterdam, I was able to complete the ridiculously lengthy post-production.

The London Independent Film Festival invited me to screen the movie at this year's festival and in a way, that screening is a welcome full stop at the end of a hugely interesting journey. What have I learned? No budget, one-man film-making and post-production is a real crippler for a start. Less flippantly, actually putting your head down and making a film puts you in a much better position to comment on others' work. Your empathy levels are sky high and with very few exceptions, you feel for most film-makers who, after all the ego stuff is scraped away, are only trying to entertain an audience for an hour and a half. Writing for this site has deepened my appreciation of any film-maker and his/her efforts to communicate ideas and tell a story in images. For some reason (or even a billion of them), Michael Bay still eludes my empathy zone.

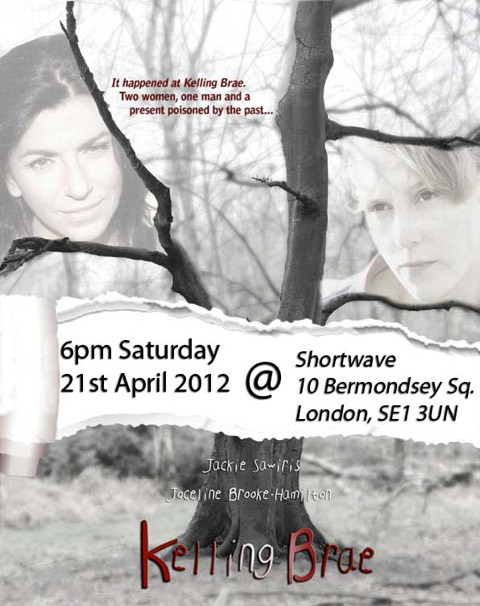

My film, Kelling Brae (which incidentally contains no explosions of any kind), is playing this Saturday (21st April) at 6pm at Shortwave (see the poster below for the address). If you're in London on Saturday and want to come along, consider yourself invited. It's free but if you are planning to come, please let me know by emailing from the link immediately below... Space is limited.

kellingbraeinvite@gmail.com

To judge if the movie is something you'd like to see, the web site with all the info is at:

http://www.kellingbrae.com/

"Films are always pretentious. There's nothing

more pretentious than a filmmaker." |

Inspiration for The Big Lebowski's Walter,

writer/director, John Milius |

Ever since I was very young, I wanted to be pretentious. No, wait. Strike that. I sat in the dark, gave myself to the storytellers and burned, arc-light bright, to do what they did. I had the ambition and faith of a blind mountaineer, having not a single inkling of how ridiculously unlikely my goals were. But I knew what a rope felt like. This was the late-sixties and the film industry was a closed shop in more ways than one. It wasn't just closed. It was locked off, pressure sealed. It was a secretive, elitist world ruled by a cadre of people whose common skill was simply knowing other people, relatives, friends... jobs for the old boys. I was driven but knew no one in the business and being raised, as were my parents, to know my place, I was not able to simply wander into a studio with an excess of chutzpah as did a certain Master Spielberg at Universal Studios. This 'place' I was taught to know was certainly not the hallowed and very middle class world of the film industry in the UK. So I bided my time, met with as many industry types that my naïve but hope-filled letters could snag encounters with and trained at the BBC. I wanted to learn what I considered to be the pivotal creative part of the film-making process – editing. It's been one of my better decisions. Editing is a significant pleasure wonderfully free from the higher responsibilities that weigh down, Atlas-like, on producers' and directors' shoulders. As the editor, it's just you and the movie. You're its chaperone, its protector, its friend and as the great film-making cliché goes, films are never finished, merely abandoned. In the end you are its co-divorcee...

In 1985, I was director Richard Franklin's assistant on a feature film being made at Shepperton Studios. It was a glorious apprenticeship. It was also a privileged peek inside someone else's creative process and while doing my job one day I came across two A4 sheets in Richard's distinctive handwriting. I'm fairly certain it wasn't a private document (why would it be just laying on his desk and not locked away?) But I was fascinated not by what it was or what words the pages contained but what the pages actually said about Richard the film-maker. I knew him to be whip smart, sensitive and driven with the powerful ability of never taking "No!" as any kind of answer. But here was strong evidence that Richard had a very exposed heart (as have most of us if we summoned up the steel balls to admit it). Richard had written a review of his own movie before a frame had been shot. He'd already made the film in his head and had accepted that a taut thriller about an elderly chimpanzee driven insane by mishandling would not paw at Citizen Kane's hem for a place at the top table. But Richard knew that Link was going to be a diverting thriller with some added anthropological thoughts attached. And so, as an Ebert-avatar, he said so on paper.

I could write a review of my own movie (how weird would that feel?) but I would have no clue how to pitch it. I know what my intentions were in making it and have no idea if any survived the creative process. This is why I envy plumbers. Water will never flow upwards. There are no such truths to cling on to making a film. The only wisdom I've found and embraced is contained in the following short sentence.

Please yourself.

Everyone else will be somewhere on the love/hate scale or be indifferent and it's not in your power anymore to affect those emotional outcomes. Just please yourself, satisfy your own ambition for the material and some will like, some will hate, some won't care one way or another – but the work is out there and that's where communication needs to be. There are many unknowable things in the creative process but I do know one thing for certain and I'll let Mr. Bogdanovich introduce the idea...

"You see so many movies... the younger people who are

coming from MTV or who are coming from commercials

and there's no sense of film grammar. There's no real

sense of how to tell a story visually. It's just cut, cut,

cut, cut, cut, you know, which is pretty easy." |

Director, Peter Bogdanovich |

Well, I can promise you one thing if you pitch up on Saturday. You'll get an honest to goodness movie. Let me explain. Composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim always maintained that he wrote songs and whether you despised or loved them, they were undeniably songs having all the ingredients of what constitutes 'a song'. Well, I've made a movie. It's not a wobble-fest of faux documentary urgency or an amnesiac assassin state of mind-style jitter-bug presentation. It has locked off shots (how dreadfully old fashioned – perhaps). It has a tripod-based point of view and it has characters and it has a beginning, a middle and an end. If you are taken with the journey it may reward you with a few ideas that may catch in the febrile wool of your imagination. If you see only what I see (all the mistakes and lost opportunities) then I hope it's raining outside and you can at least be dry while you watch it.

It's very odd to have the simple ambition to divert an audience for 90 minutes and then realise with a profound shock that to make this diversion has taken a significant percentage of your life. Thoughts then have to flow towards the area dominated by the question "Was it worth it?" My god.

My good god...

If I add up the hours...

Having the idea. Writing the 115 page screenplay... Casting the actors. Preparing the shoot. Getting permissions. Shooting the film. Editing and track-laying. Smashing the lost disk to smithereens. Re-track-laying. Grading and mixing. Backing Up Materials...

It was worth every second...

Can any work of art or craft be deserving of the optimum time required to appreciate it? From my perspective, my movie is not a work of art (whatever those three words may mean to you) but what work out there is worth the time to appreciate fully? Our current cultural climate is obsessed with speed. The turnover of material in our media drenched world is stupefying. A career in stand up forty years ago could be expended on TV in a day. One of the saddest things about being a parent is to acknowledge that today's cinema will never mean as much to the next generation as it meant to you at their age. It's hard to be shocked by a splash in the face when you're scuba diving. Few movies reverberate and rattle around in your head with images and ideas now almost a part of your thought process. And no film-maker ever knows the effect their work may have going in. That's for the movie gods to decide and those timorous beasts have been on hiatus for years.

I'll leave the penultimate words to a master. He may not deliver what this site craves and celebrates (and his latter work has come under some significant fire, narrative-wise) but boy, does he know his onions.

"Pick up a camera. Shoot something. No matter how small, no

matter how cheesy, no matter whether your friends and your sister

star in it. Put your name on it as director. Now you're a director.

Everything after that you're just negotiating your budget and your fee." |

Aquanaut, honorary Na'vi, and writer/director James Cameron |

Raising a glass to the film-maker in you and then to good negotiation. See you on Saturday?

|