Preface

I wish to offer a caveat, a short admission of my cultural and temporal imprisonment. I am who I am (though mercifully I don't eat that much spinach). Unlike our esteemed editor, Slarek whose prodigious and internationally diverse movie viewing makes my choices seem somewhat anorexic, I admit to a western bias that shames me in public on certain occasions. I am also concretely placed in a specific era and so certain work will be beyond me in more senses than one. I am writing about what makes 'great' directors and yet I have such a small sample to reference and they are mostly (or all bar one) dead white males. In the spirit of full disclosure, I admit my evident and ingrained prejudices so please feel free to add your preferred directors to any selection I put forward. How can I make an argument for Ingmar Bergman when I have seen so few of his films and how can I make an argument for Steven Spielberg when I've seen way too many of his? There is a general cultural and critical consensus on which I'm basing my foundations so I hope I'm not that far off the mark.

Yes, 'ineffable' means 'too great or extreme to be expressed in words,' but as words are all I have to communicate, they will have to do. So let's ignore what the late, great Dennis Potter had to say about words... "You don't know where they've been..." Greatness in film direction is usually a judgement call or critical consensus draped on to the willing (or unwilling) shoulders of a man or woman (alas, all too few times, a woman) who has somehow lucked (yes, lucked) into crafting works in his/her era that can be universally praised as having outstanding artistic value or merit. Or does luck have nothing to do with it? You may be surprised to know that the official name for the Oscar is the 'Academy Award…' (yes, we all knew that bit) '…of Merit'. Not as appealing as 'Oscar', is it? This granting of 'merit' is quite simply caprice personified as a little gold plated man. It's like most things in life, entirely down to personal and highly variable and all too human opinions (in the Academy's case, those of venerable and mostly older men). Shoe-in performances like Heath Ledger's Joker in The Dark Knight are not reliably annual occurrences. A perfect example of this capriciousness was at the 2008 Oscars when No Country For Old Men bested There Will Be Blood for the top gong. When asked what were the reasons for choosing one over the other, an Academy spokesperson said "We chose the one whose ending we disliked the least..." How scientific...

The granting of 'merit' is also a direct sibling to our relationship with money. Money is only given the power it has because most people on this planet have become in thrall to its power by dint of simple agreement and acceptance. What if we suddenly all saw money for what it is, a delusion; civilisation would fall apart. Those notes and coins in your pocket in a survival scenario mean absolutely nothing but look how our psychology alters dealing with the damned stuff. And we acquiesce to that global delusion everyday. It's a bizarre social glue adhering a currency to an illusory sense of structured worth. If we're all under its spell then its power becomes tangible. So a great director is a great director because enough time has passed and enough people in the know have decreed it thus. But what do great directors have to do to have greatness thrust upon them? They have to make 'great' films for a start. No cine literate scholar would deny that there are 'greats' in film direction. Forgive my parochial and western bias (I'm a Brit, it's part of the territory, see the Preface) but off the top of my head, here's a generally accepted top ten;

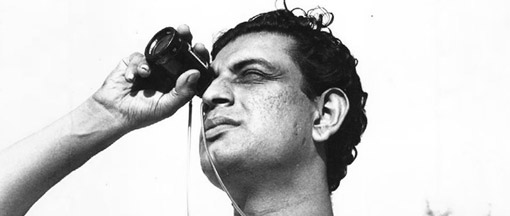

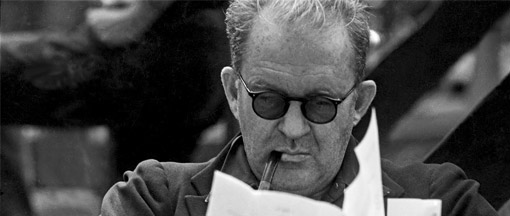

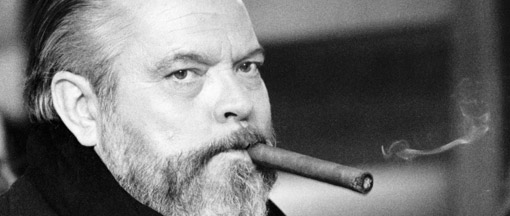

Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, John Ford, Akira Kurosawa, Ingmar Bergman, Stanley Kubrick, Billy Wilder, Satyajit Ray, Federico Fellini and…

Who should be my tenth just from memory? No living director, for sure. You cannot be great and still be alive (time is the first judge of greatness). Oh, of course, it has to be...

Jean Renoir.

OK, we all knew Kubrick was a great before he went beyond the infinite in 1999. But here's the punch line. There are many films directed by the above ten that I have never seen and possibly will never see. Ray's work has been championed by many who know much more than I ever will about his great skill as a film director. But I can count how many films of his I've seen on the finger of one hand. He's one of those 'greats' who's a given in any Sight and Sound poll and I do not deny that. But we are all still prisoners of our era, our tastes and our culture to a degree. I've yet to fill in the significant blanks in my own cine-education. That said, I have a Jacques Tati Blu-ray box set waiting for my attention. In many ways, greatness and its appreciation is all about time - for the director, it's staying relevant through the decades and for the audience, it's carving out slices of the stuff in lives more assaulted by media than in any other time in history. And let's play devil's advocate... Sometimes an unhealthy piece of junk food is preferable to more noble comestibles. Sometimes a Singin' In The Rain is far more palatable than The Seventh Seal and yet I can still acknowledge the latter's greatness over the former's joyousness. As this site's unofficial Hollywood correspondent, I probably eat more metaphorical junk food than most.

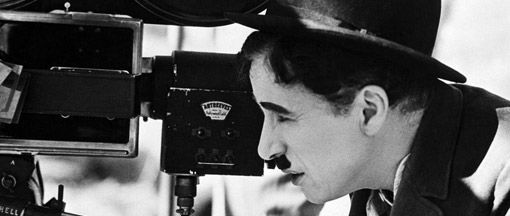

Many would argue that Charles Chaplin belongs on that initial list (who to bump off?) but I never had a personal connection to the man and stand in awe of the general perception of his greatness but not of his work. Give me Stan and Ollie any day. So what do we have so far? Directors who have made films deemed artistically relevant and whose reputations have survived the passage of time. Igor Stravinsky (yes, the composer) shares an experience with director Jean Renoir. Their respective masterpieces (judged over time) were both booed at their premieres. So yes, time has to be part of the gentle ascent to this narrow ledge of greatness. I am going to take a leap of faith and suggest another top ten that will take on the mantle of greatness taken from today's living crop. But for the purposes of suspense, that's for the last paragraphs. Hey, don't go… No skipping to the end.

Andrew Sarris' famous book, The American Cinema written in 1968, introduced the idea of a 'pantheon' of film directors. He pushed the frankly silly 'auteur theory' to the fore, an idea punctured and deflated by the word 'American' in the title of his own tome. Despite being a seminal and considered work, it's been blasted for being too subjective and highbrow. It's a great read but because it was written in 1968, there are many careers that ballooned, vastly improved or self-destructed beyond the ceiling of the late sixties and 'greatness' could only be placed at the feet of the significantly older directors. Just for your information, here are Sarris' self-coined 'pantheon' directors listed in alphabetical order…

Charles Chaplin, Robert Flaherty, John Ford, D.W. Griffith, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Buster Keaton, Fritz Lang, Ernst Lubitsch, F.W. Murnau, Max Ophuls, Jean Renoir, Josef von Sternberg, and Orson Welles.

And this is the paragraph that describes why they were chosen…

These are the directors who have transcended their technical problems with a personal vision of the world. To speak any of their names is to evoke a self-contained world with its own laws and landscapes. They were also fortunate enough to find the proper conditions and collaborators for the full expression of their talent.

That last sentence must be that quality of 'luck' I mentioned earlier. I love how Sarris takes nineteen words to say 'they got lucky'. Film directors on larger budget films now have fewer problems technically if we assume that if it can be imagined, it can be made visual (that's a flippant throwaway but...) Computer generated imagery has removed a number of technical barriers that Hitchcock (for example) was famous for solving with great, practical ideas. Reportedly, Kubrick was utterly astounded at what was technically possible after having to digitally remove some offending copulations from a sweeping shot in Eyes Wide Shut. Imagine old Stanley getting to make his beloved Napoleon with 2014 tech... Film directors use whatever technology is available to them to keep pushing the limits of the craft. You may dislike/loathe/abhor (delete applicable) Avatar but there is no question of Cameron's talent in realising the hitherto unrealisable no matter how spectacularly dull and clichéd the narrative. I was heartened to see Nolan's Interstellar spacecraft were nearly all variable scale miniatures. In the pre-CG days, directors had to rely on their wits (and their crew's practical ability) to create believable spectacle. In Hitchcock's Foreign Correspondent, a plane crash seen from the pilot's point of view was achieved with back projection of the ocean coming closer and an explosion of water that destroyed the back projection screen so quickly it did not register on film.* It's a great effect (in the parlance of the times, this was known as a 'gag') and if a modern audience stopped and thought about what it was seeing, it collectively may conclude that a plane interior was dropped into a vast tank. In order to keep appreciating the real graft of the directors of years gone by, you have to understand the real world limitations placed upon them. In fact, it occurs to me that we may have to divide the mantle of 'greatness' into two specific periods - BC and AD (Before Computers and After Digital)...

So with the exception of saying to the cinematographer, "Put it here," regarding the placement of the camera and suggesting its movement and the size of the lens, what do great directors do? Obviously their relationship with actors is key. A great performance is mostly down to the talent of the actor but a hugely variable percentage of its effectiveness must be laid at the director's feet. I'd have to credit William Friedkin with a greater than fifty per cent involvement in that extraordinary last rites scene in The Exorcist where Father Dyer, shaking and physically in some shock, blesses Father Karras as the latter dies. What was Friedkin's direction? He asked the real priest William O'Malley playing Dyer "Do you trust me?" Dyer said yes, and Friedkin smacked him hard in the face… "Roll 'em…" There are variations in the detail of this story but all versions include the smack. It's not exactly the perverse manipulation courtesy of director Eli Cross in The Stunt Man (who announces to his lead actress that her parents mistakenly sat through her sex scenes rushes upsetting her just the right amount for the scene being shot at that moment) but it's bloody close. The director/actor relationship is key on any movie. Until CG has progressed to being able to faultlessly mimic an actor's performance (we can't be too far off if Andy Serkis' ape Caesar is anything to go by), we are beholden to the actor to guide us through the narrative. Some actors have given subjective clues to what constitutes great direction.

William Hurt sang the praises of his director, Lawrence Kasdan, on Body Heat, for saying the single one-syllable word, "less", in the scene when he gets the news that his fellow murderer had changed the will of the murdered husband. Gary Oldman is moved to tears talking about the sensitivity and direction he received from legendary TV director Alan Clarke. Tony Curtis, in his second bit part film role, always remembered one specific piece of direction. He had a single line but was struck by the simplicity of director Michael Gordon's directness. On hearing how Curtis would deliver the line he simply said "All you want is a tip," and walked away. Curtis did the line, smiled the biggest smile (and Curtis was a hugely appealing actor), et voilà, cut and print the first take. So great direction is knowing what the character wants and communicating this to the actor. That's a part of it. Ridley Scott and Quentin Tarantino have both been known on occasion to simply say "Make me care," as an all-in piece of thespianic motivation. Alfred Hitchcock loathed all the actor introversion bullshit and has been oft quoted saying that an actor's motivation is his/her pay cheque.

So, to recap; you have to:

-

…know the best place to set the camera (David Fincher said that there were only two ways to 'cover' a scene. "And one of them was wrong…")

-

You have to know the characters of your narrative well enough to know what their desires are scene to scene and then to guide, cajole and push actors to the best and most convincing interpretation of their character.

-

You have to be a supreme communicator to get the best not only from your actors, but your crew too. All the decisions are yours to make but make a bad one and the whole film can suffer.

George Lucas trumpeted the fact that his 1999 Phantom Menace contained the world's first digitally created lead character! Hurrah! Except it was the universally loathed Jar Jar Binks. By the way, Lucas will not be on my list. His luck has been preternaturally vast in the last two aspects of what's required to be a great director.

- The audience must support you.

As much as show business is show, it's mostly business and if you are the greatest film director in the world, you're not much without an audience. Remember, M. Night Shyamalan didn't make The Sixth Sense a hit. We did, the audience.

The last of the two final aspects, of course, is up to the movie gods… Even Spielberg admits these deities most definitely exist... (tongue in cheek, of course).

- It's luck, pure and simple.

On one hand, the movie gods will bless you and while you're in Hawaii recovering from one of the worst experiences of your life with a recalcitrant English crew, your film becomes the most successful film ever made up to that time - again Lucas with Star Wars... He got lucky because we adored en masse what he'd made. Hollywood is trying to factor luck out of the equation now by taking few to zero chances on original movies. Have you noticed the sly shift to known quantities, sequels, movies based on stories or TV shows audiences are pre-aware of? When was the last big budget original movie from Hollywood? Christopher Nolan seems to own that concept now (not including his Dark Knight trilogy). This is why Sony is re-starting yet another Spider-man franchise (Jesus) with a third actor… How many times can Peter Parker be originated?

Despite my thirty-one years of experience in post-production, I won't go on about the importance of editing. I must say that it is hugely important and a strong and mutually supportive relationship between editor and director is always necessary. It may be as important a relationship in filmmaking as the one between director and actor. There's a reason some directors stick with editors they click with. Spielberg and Michael Kahn have been together for almost forty years! So what about today's crop of film directors or has digital technology blurred everybody's work into a virtual camera mish-mash of styles and substances? Whose voices are heard above the patter of tinny feats? Who are today's great cinematic artists likely to be revered and remembered long after we're all "just dust on the wind, Dude...?" That's a big question...

An Extremely Unlikely Omission

There is one very obvious name perhaps criminally absent from my top ten. Perhaps. While some movies on his CV are undeniably classics, his career came to an odd fork in the road and this hugely popular director started to move towards creating a legacy of new work that could be seen more as artistic and significant, more than just the dizzy outpouring of a talented, unique, somewhat sentimental voice whose sole aim was to get cinemas packed. Steven Spielberg (gasp) grew up. As a young man, he was very open about the goal of pleasing cinemagoers being the most important ambition of the film director, not artistic self-expression. He will be revered for a great many years in the future (he is the most successful modern director working today after all) but he's not on my list because I felt he was being more honest cinematically as a younger director whatever his base, populist motives. His later work is burdened with artistic ambition and a longing to be accepted as a filmmaker of some weight. His lightness of touch was one of his best attributes. I couldn't discern a single unified voice from the man who made almost simultaneously two films, one about dinosaurs and the other, the holocaust, as accomplished as both Jurassic Park and Schindler's List were... Spielberg needs no backslapping from me. He and his films have made Hollywood history and so his 'greatness' is assured. But I wanted those on my personal list to be artists because they had no choice not to be, not because they felt they needed to be. I do hope that makes sense because the idea of leaving the man who directed Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. off my list is frankly, surprisingly upsetting...

To Those Who Skipped To The End…

So let's get to my modern 'greats', those who may be fêted in the same way as Alfred et al fifty years hence. It's a safe bet that the same older ten will still be revered – after all, filmmaking was a very different craft and discipline from the 20s to the 70s, the fifty years of having to place almost everything in front of the lens and having to perform insanely complex optical and photo-chemical tricks to add anything in post production. But let's concentrate on those who have created lasting works of cultural, social and political significance, works perhaps not praised or supported at the time but those that will stand the test of such a merciless crucible. Also bear in mind that today, fewer films are being made (in the bigger production sense) so even if you're an 'A' Lister, you may not have that many films on your CV. Maybe I'll chicken out and just give a top ten of movies and then infer from them the greatness of their directors – but that (like a burly, gay policeman) is a huge cop out. We're talking of directors whose bodies of work are impressive in and of themselves. There's one name that keeps nudging me, one name of a man who is a true champion of cinema who has made consistently great movies with a single artistic identity and made some strides to imprint his sensibilities into the CG present. It's too easy to blame CG for a lot of unfounded sins against filmmaking, so I'm not going to but for this lot (Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, Raging Bull and The King of Comedy) Martin Scorsese has to be a contender.

I'm trying not to be populist (it's really hard) but which other director's work today has a consistency running through it, whose films are always intelligent and absorbing with an unjudgemental view of human nature that courses throughout all his work. Yes, he began his career making intelligent horror movies (emphasis on 'intelligent') and he became synonymous with horror as a springboard into mature human nature movies. Is it such a leap to imagine David Cronenberg will be revered as a great? I love the story of Scorsese being afraid to meet Cronenberg because of his early work. When they did meet, Cronenberg countered with "You were afraid to meet me? The guy who directed Taxi Driver?" He had a point.

Eight more; I'll be brief. Please remember the western bias colander I have little choice in filtering the following through… So I'll start with a Japanese great!

Hayao Miyazaki – thanks to my son for exposing me to this extraordinary man's work… His imagination and power delivering emotional sucker punches need no reminding from me. I've not seen everything he's done but in fifty years, I'm certain he will be held in some awed reverence. There is something about directors who animate by hand that promotes profound respect.

Ang Lee – With the possible exception of the movie he was born to direct ("You won't like me when I'm Ang Lee," The Incredible Hulk), his films are always visually breathtaking. I can never really forgive him for not thanking or acknowledging the extraordinary effects work of the recently bankrupted FX company Rhythm & Hues when he picked up his Oscar for Life of Pi but his talent cannot be dismissed.

Wes Anderson – I know he's not made that many films but hey… His is a distinctive, self contained and artistic worldview and he keeps his collaborators constant like a certain Mr. Ford. You always know when you've watching a Wes Anderson movie and this dovetails nicely with one aspect of Mr. Sarris' definition of a 'pantheon' director.

The Wachowski Siblings (counting as one) – apart from loving the idea of a transgender 'greatest' director (all hail Larry/Lana), it has to be said that The Matrix rewrote the rules of action cinema and for good or ill kick-started the era of gravity defying action and human invulnerability. I think Cloud Atlas is a work of genius and do appreciate I may be in the minority. Maybe there's not enough on the CV to warrant them being awarded true greatness but we'll still be referencing their films in fifty years, I'm sure of it.

Lars von Trier - despite the fact that he would probably spit in my face if I even suggested he may once be hailed as a great, there are damn fine reasons for having him on this list. He bends and breaks cinema to his will. He manages to be hugely provocative, emotionally resonant and truly cinematic. He uses his craft in the same way knights use lances and it's all the better for the art of cinema that we get thrown off our horses every now and again.

Francis Ford Coppola - OK, so after (or maybe during) The Godfather Part III, he went off the creative boil and started supporting his offspring's efforts as an executive producer. But how can you dismiss a man who made - oh for God's sake, look him up on IMdb. Like Scorsese, this man has the right to compete for greatness with four films alone. Do I need to list them? Apocalypse Now, The Godfathers I and II, and The Conversation are all way, way up there...

David Fincher - OK, my wild passion for Fight Club notwithstanding, Fincher consistently makes intelligent movies but on his own terms. You never get the sense that executives fiddle after Fincher delivers his cut. Meticulous to the degree that had Robert Downey Jnr. leaving jars of his urine around the set of Zodiac to make a perhaps unsubtle point, Fincher has inherited the Kubrick mantle of detail oriented. Again, he's working in an age where you cannot turn out a few films a year so his CV is not jam packed and it is curiously peppered with very wordy films but his command of the more high tech end of the craft is second to very few.

The Coen Brothers - Joel and Ethan Coen will not be boxed in with any casual generic label. The range and diversity of their extraordinary movies is undeniable. Hits and misses alike, all coalesce into a single body of work that is consistently fascinating, eclectic and despite their detractors' accusations of a lack of emotionality, surprisingly warm. And their work passes the François Truffaut test of quality cinema. Their movies can be watched and re-watched and there's always something you missed last time around. Their work has density both visually and narratively. You'll have to forgive the two remakes on the CV (what were they thinking?) but with this lot sitting comfortably, (Fargo, The Big Lebowski, Miller's Crossing, No Country For Old Men and O, Brother Where Art Thou) I can't see their legacy dying too soon...

But this article has to and now's the time. Let me know if I've missed out someone really obvious (we're talking about directors with a significant body of quality work, men and women all agreed by most critics and commentators to be in possession of a unique voice). Cut. And that's a wrap...

* Watch the Hitchcock 'gag' I mentioned earlier here... https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HfebgvBWUtQ

|