|

So

it's been and gone and the speeches have been made and all

the backs have been slapped, and despite the hard-to-avoid

news of Eastwood's third Best Director award and Scorsese's

fifth rebuff, I still haven't even bothered to check who

else won what. Why? I really, truly, honestly don't care.

Once I used to. Really. In my innocent youth. But not any

more. In the past couple of decades things have changed.

OK, I've always found it possible to find a whole bucket

of films that I think are better than the one that bags

the Best Film gong, but recently a fair number of such winners

have struck me as sitting somewhere between drearily mediocre

and offensively awful.

In

my time I have known plenty of seemingly sensible people

who have stayed up late to watch the Oscars. They also claim that

they don't care who wins, but apparently sit there shouting

at the screen like soap opera fanatics in front of a Eastenders special. This is hardly surprising given the modern obsession

with the cult of celebrity, the shallow over the meaningful,

and the populist over the genuinely inventive, and you would

be pushed to find a more self-indulgent and crass expression

of celebrity culture than Oscar night.

Repeatedly

hyped as a celebration of the greatest achievements of the

movie year, it should be remembered that although in theory

any film released in the preceding twelve months can win

an Academy Award, it is essentially an American prize for

(largely mainstream) American movies, with a special category

set aside for a film in which the actors do not speak God's

language. Given that the most daring, most adventurous,

most entertaining and most groundbreaking films are almost

never American mainstream movies these days, the selection

is inevitably going to be a compromise collection at best,

especially as the American films that really do matter – usually the low to medium budget independents – are rarely

even considered, being thought of as the scruffy urchins

of the film world and sidelined to Sundance and Raindance.

If such a work does catch the public's imagination and make

the necessary dollars, then it may get a token nomination

in one or two categories, and the Academy can

always reward the big budget remake or wait until the director

goes mainstream and makes something less 'quirky'.

It's

hard for independents to qualify anyway – the Academy prefers

big films about big themes with big names, and preferably

American themes and American names, though they will tolerate

a few Brits as long as the subject matter is appropriately

'universal' and there is not too much controversy attached.

Genuine controversy scares the Academy, though if it goes hand

in hand with financial success then chances are sometimes

taken, as with Michael Moore's box-office hit Bowling

for Columbine. But that was soon sorted by his notorious acceptance speech, and despite making over $100 million and

becoming the most financially successful documentary of

all time, Fahrenheit 9/11 was excluded

this year on a technicality to avoid any more trouble from

Big Mike. I have a sneaking suspicion that some of the votes

for Eastwood this year were prompted in part by his very

public threat to kill Moore if he ever pointed a camera

at him.

That's

not to say that US mainstream cinema is not capable of producing

great films, even if this an increasingly rare phenomenon.

Take Curtis Hanson's superb L.A. Confidential, a film that was rapturously received on its

release and as looks set to attain classic status in the

course of time. It boasted two superb central performances

from Russell Crowe and Guy Pierce, top notch cinematography

and masterful direction. It did win for its screenplay,

which was also excellent, but the only acting award went

to Kim Bassinger, who for me was far and away the film's

weakest component. The big gongs of Best Film and Best director

went to....wait for it....Titanic, a godawful,

overblown nightmare of a movie whose status has slipped

alarmingly in the past few years, with even many of those

who initially sang its praises later admitting that it was actually

a load of old tosh. But it was a BIG film with a BIG story,

it was about a real historical event rather than L.A.

Confidential's fictional and noirish tale of cops

and corruption, it had lavish sets and gargantuan effects,

and it had Leonardo De Caprio, a rising and good looking

young American star who had already bagged an Oscar for What's Eating Gilbert Grape?, whereas L.A.

Confidential featured two Australian actors who

had yet to prove their worth on the US circuit. That, of course,

would soon change. And let's not forget, that though L.A. Confidential did make a profit, more

than doubling its $35 million budget on its US release, Titanic is estimated to have cost a ludicrous

£200 million and went on to make three times that

in the US alone, and a truly terrifying amount in worldwide

receipts and TV and video sales.

There

are a whole number of reasons a film will be up for the

top gong, and quality is rarely at the forefront. Box-office

business appears to be the key qualification – the mighty

dollar has replaced the mighty visionary as the major requirement

for award recognition. Lead acting gongs are usually (although

not always) reserved for the already famous, and you can

take just about any Best Actor or Actress winners in recent

years and find a more committed, daring or compelling performance

elsewhere. Look at Ellen Burstyn in Darren Aronofsky's extraordinary Requiem for a Dream, an astonishing and

bravely unflattering performance in a dark, dangerous and

semi-experimental work, one too risky for the Academy – she may have got the token indie nomination, but what chance

did she stand against superstar Julia Roberts as the plucky and

determined Erin Brockovich?

The

slide into mediocrity has been a steady one that followed

the now well-documented move following the huge success of Jaws and Star Wars from creative film-making to

more formula works that score big bucks in their opening weekend. In the 1970s the Best Film Oscars

were often awarded to genuinely groundbreaking and sometimes

boldly realised works such as The French Connection, The Godfather and One Flew Over

the Cuckoo's Nest. It should be noted, however,

that another 70s film that has achieved genuine classic

status, William Friedkin's The Exorcist, only won in a couple of technical categories, despite being widely nominated and setting the box office

on fire. Sorry,

but that's another general rule for the main awards: dramas

are fine, but genre works – horror, science fiction, comedies,

thrillers – are somehow thought to be comparatively unworthy, at least

until they achieve rare and unexpected mainstream

respectability. This happened in 1992 to Jonathan Demme's The Silence

of the Lambs, landing Anthony Hopkins

a Best Actor Oscar for a colourful performance in a role

that had been played with considerably more menace by Brian

Cox in Michael Mann's Manhunter. Thus despite

being one of the most daring, exciting, frightening and

brilliantly made films in cinema history, The Exorcist lost out to The Sting, an entertaining

but essentially safe viewing experience that had the

good sense to avoid including a scene in which a possessed

young girl bloodily thrusts a crucifix between her legs

and shouts "Let Jesus fuck you!"

This

anti-genre snobbery ensured that industry demiGod Steven

Spielberg would not win for his finest film, Jaws,

or two that are held in almost equally high regard (not

by me, it has to be said), Close Encounters of the

Third Kind and E.T., but allowed him to score for Schindler's List, partly on the basis

that, like Titanic, it was a big film about

a big story that was based on fact. And it has to be said that Holocaust tales,

no matter how exploitative, often find favour with the Academy,

hence the very unusual three nominations for Roberto Benigni's

non-English language Life is Beautiful.

Horror films are still held in low regard and horror films

with yucky effects especially so. And so the slickly made

but somewhat saccharine study of how divorce affects a young

child who is caught in the middle that was Kramer vs. Kramer (social issue, respected writer/director, two big name actors

in the leads) was voted Best Film in 1980, yet David Cronenberg's

powerfully realised and genuinely disturbing but very low

budget and visually nasty horror take on the same subject

that was The

Brood was almost universally dismissed,

an injustice that at the time was only discussed at all

by genre writer John Brosnan.

|

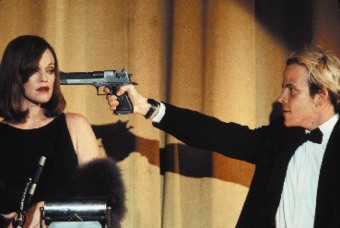

| Now this is my idea of an awards ceremony |

The

family issues of Kramer really fired the

Academy up, and the following year we had more big name

actors pretending to be down-to-earth ordinary folk with

big family and relationship problems in Robert Redford's Ordinary People (social issues, ordinary

Americans, big star names, big director) and a couple of

years later with Terms of Endearment (ditto). In between, Colin Welland announced that the Brits

were coming with Chariots of Fire, an annoying

tale of plucky personal triumph and public school notions

to honour that appealed to both American sentimentality

and a skewed perception of what England is really

like. Ken Loach's powerful and altogether more honest social dramas don't tend to even

get a mention to Academy members. But then he's a great director.

Scale

and reputation also played a key role in the Best Film shouts

for Richard Attenborough's Gandhi and Milos

Foreman's Amadeus, both fine films that

were also historical dramas that had BIG on

their sides in every respect, as did the lushly shot and

overblown commercial for the African Tourist Board that

was Out of Africa and the beautifully costumed

history lesson of Bertolucci's The

Last Emperor.

It

was then that things really started to slip. Barry Levinson's Rain Man felt like a film specifically

designed to grab Oscar attention – big stars giving 'serious'

performances, the highlighting of a not-that-well-known

condition, a famous and respected ex-indie director who

had moved into the mainstream, and the chance for an actor

to play one of those roles that just everyone is going to

remember him for. The result? One of the most tiresomely

over-praised films of the decade. But parts of it were

at least watchable, which is more than can be said for next

year's winner, the utterly wretched Driving Miss

Daisy, which was memorably shat on by Public Enemy

in their spot-on musical assault on film industry stereotyping, Burn Hollywood Burn.

Big

star Kevin Costner made a big film about a big (American

historical) subject with Dances With Wolves and won in 1991, and three years later Spielberg won with his

big holocaust film, but it was in 1995 that things

hit rock bottom with awards piled on what remains for almost everyone

I know one of the most nightmarishly awful experiences they

have every had in a cinema, Forrest Gump.

This is the film that most perfectly illustrates where the

Oscars have ended up: it was a big film in every respect,

covering decades of a man's life and (this is very important)

key events in American history; it starred Tom Hanks, who

was on his way to becoming the country's most popular star;

and it featured then gasp-inducing special effects that

placed the lead actor alongside a number of famous figures,

the perfect melding of historical America with the fakery

of La-La Land. And it was absolutely fucking unwatchably

awful. You don't agree? Tough, I don't care. One of the

most satisfying moments for me in any film in recent years was when the title character in John Waters' cheesily

enjoyable Cecil B. Demented led a group

of self-styled film terrorists onto the set of Forrest

Gump 2 and, during a reprise of that horrible (and as fellow reviewer Camus has pointed out, nonsensical) "box of chocolates" speech, machined gunned everyone on set to death.

Size

continued to be everything with the wearily over-rated Braveheart (big story, based on a historical event, big star directs, the Brits are the bad guys) and the primly tolerable The English Patient (big personal story, sweeping locations, lovely cinematography),

but peaked again the following year with the wretched Titanic.

Many would argue that Ridley Scott's sword, snot and sandals

tale Gladiator (also a size-driven winner

in 2001) successfully melded the

scale of the setting and effects with a genuinely gripping

story, but you'll not find much sympathy for that view here

– stand Gladiator next to Spartacus and it frankly pales. As for A Beautiful Mind and Chicago – the less said about them

the better.

Perhaps

the most dispiriting aspect of the awards is that the selection

is so narrowly focused. The Internet Movie Database lists

almost 15,000 films released in 2004, yet there

is a sense that each year a mere handful of them are chosen

and then the available awards divided up between them. And

even then that handful has not been selected through careful

consideration of thousands of hopefuls, but as a result

of relentless lobbying by the studios and distributors.

The

question, of course, is does it matter? For many it's not

about the films at all, but the glitz and the glamour, the

pleasure of watching emotionally insecure performers make

ridiculous acceptance speeches and burst into tears at the

drop of a tiara. But it also represents everything that

is superficial and hollow about American mainstream cinema,

a gigantic firework display with no substance that serves

to illustrate all to clearly why film is still held is such

low regard in some quarters, and not taken remotely seriously

as an art form.

Big

Oscar winners nowadays are the high school jocks of the

movie world – well built, good looking, hugely popular,

in all the magazines and on all the TV shows, but contributing

precious little to the development of the art. That is

the job of the outsiders, the scruffy independents and the

foreign language movies that most western viewers simply

will not watch. They'll wait for the remake, the big budget

Hollywood version in which actors they recognise play to

a formula they feel safe with in a language they can follow without recourse to subtitles.

As

a final thought, ponder on a few of the names that have

never won a Best Director Oscar, despite making films that

are widely recognised as classics: Stanley Kubrick, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks,

Sidney Lumet, Robert Altman, Oliver Stone and Charlie Chaplin.

Nowadays, that's a badge these gentlemen, or at least those

still surviving, should wear with pride. They are in good

company.

|