| Self-Defence And State Paranoia |

|

If film history consists of an ongoing conversation between films and cultures, between cinema and history, and among the films themselves, no two films at the festival spoke more directly to one another than Bernadette: Notes on a Political Journey and The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975. Here are two documentaries that consider a similar period, similar politics and similar people. These films make plain the connections between Black revolutionaries in the African-American ghettos of North American and Irish revolutionaries in the Catholic ghettos of the North of Ireland. Each contended with waves of reactionary racist violence triggered off by growing popular demands for equal rights and social justice. Both Bernadette Devlin and the Black Panthers dedicated their lives to the wellbeing of their people, took on deeply embedded forms of structural racism, and defended their communities against violent attack. They did so while consistently insisting that, as Miles Davis said, "Knowledge is Freedom. Ignorance is slavery," and while acting in the spirit of Franz Fanon's belief that, "Freedom is not a commodity which is 'given' to the enslaved upon demand. It is a precious reward, the shining trophy of struggle and sacrifice."

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, Richard 'Tricky Dicky' Nixon, Lord Paisley and their ilk, in contrast, seemed to base their political (mis)conduct on the ideological premises outlined in those chilling Orwellian slogans: "War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength." Ever eager, like McCarthy before him, to demonise dissidents, Hoover declared the Black Panthers the "greatest threat to the internal security of this country," and identified the Oakland Panthers as "the most dangerous and violence prone of all the extremist groups now operating in the United States." It says much about the Orwellian worldview of Hoover's successors, their increasing paranoia and inclination to generate a climate of passivity and fear, that Bernadette Devlin was deported from the US in 2003. Although she had been visiting the States regularly over a 30-year period, she was denied entry while changing flights in Chicago en route for New York. The State Department declared that she, " . . . poses a serious threat to the security of the United States." Her daughter, Deidre, accompanying her at the time, wittily remarked: "I can't imagine what threat they think she poses to US security. Unless it's the threat of knowing too much and saying it too well." Times change. When Bernadette Devlin visited the US on a fundraising tour just after her 1969 election victory, she had been welcomed with open arms and celebrated as a heroic civil rights campaigner. She was even awarded the Key to the City of New York, which she duly donated to the Black Panther Party as a mark of respect.

| The Black Power Mixtape 1969-75 |

|

In Alan Parker's The Commitments, his film adaptation of Roddy Doyle's novel, the central character, Jimmy Rabbitte, quotes James Brown and deploys a class-conscious, internationalist logic to unite members of his rag-tag-bobtail band behind his dream of a tight Dublin soul outfit. He tells his compadres: "Do you not get it lads? The Irish are the Blacks of Europe. And Dubliners are the Blacks of Ireland. And the Northside Dubliners are the Blacks of Dublin. So say it once, say it loud – I'm Black and I'm proud." Jimmy Rabbitte's phrase could doubly have been applied to the North and the citizens of Derry and Belfast. That assertive, defiant phrase – "Say it loud: I'm black and I'm proud" – implies much of what the Black Power movement was all about for those African-Americans who, like their Irish contemporaries, grew up in an unjust society and were not prepared to grow old in one: pride, communal solidarity and empowerment, self-respect and self-defence. Göran Olsson could relate to that phrase as surely as Bernadette Devlin. Prior to creating The Black Power Mixtape, he directed Am I Black Enough For You? – a documentary on Philly Soul and singer Billy Paul.

The Black Power Mixtape has been widely reviewed, so, many readers will be familiar with its content, which is why I left it until last. It looks at the Black Power movement from just before the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King to the enforced resignation of Richard Milhous Nixon. The film begins at a time when those who remained committed to non-violence were increasingly regarded as out of step by an impatient generation of radicals who believed physical force was necessary for self-defence. Like Leila Doolan's film, it borrows from the techniques of narrative cinema to tell its story. Like Doolan's film, too, it is arranged chronologically and built from superb archive material; in this instance, splendent 16mm footage shot by several inquisitive Swedish journalists, raw material that had been buried in the basement of the Swedish Broadcasting Corporation for 30-odd years. Rumours had long circulated in the Swedish filmmaking community that an extensive cache of footage relating to the Black Panthers was hidden in underground vaults in Stockholm, so Olsson's excitement must have been intense when he stumbled on this documentary treasure while researching Am I Black Enough For You?

Olsson says he knew immediately that he had to bring it into the public sphere. He took a significant step toward doing so when he called, unannounced, at the offices of Louverture films, eventually enlisting the essential help of Joslyn Barnes and Danny Glover. It would be hard to imagine a more perfect pair of producers for this film. Joslyn Barnes's credits as a producer include Cheikh Oumar Sissoko's masterpiece Bamako, Apichapong Weerasethakul's magnificent Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, and Soundtrack for a Revolution, a documentary about the protest songs of the Civil Rights Movement. Danny Glover, one of the world's best-known actors and a respected political activist, is currently working on his directorial debut, Toussaint, a multi-million dollar epic telling the story of Toussaint Louverture, leader of the 18th Century slave revolt that lead to the Haitian Revolution. We must be grateful to Barnes, Glover and Olsson for bringing us this footage, while remaining incensed that it remained hidden for so long. That it has not seen the light of day since a solitary screening on Swedish TV back in the '70s says much about the way the history of marginalised groups is itself marginalised, and about the fear the Panthers instilled in the dark, cold heart of the US cultural and political establishment.

Erykah Badu says on the commentary: "We have to tell the story right. And that's why black people have to document our own history – or the history becomes twisted. We get written out." In sharing the obvious ironies of that comment with audiences, Olsson shows an admirable capacity for self-deprecation and self-criticism. He also highlights the striking lack of coverage of the Panthers and the Black Power Movement within mainstream US film culture and journalism. The Panthers were clearly considered too hot to handle in the US. Mario Van Peebles addressed that lacuna with a fictional account of the movement in his 1995 film, Panthers, scripted by his father, Melvin Van Peebles, who features on the commentary of Göran Olsson's film. Van Peebles Senior's 1971 cult classic Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song – dedicated to "All the Brothers and Sisters who had enough of the Man," and "Starring: The Black Community," is one of the few films to find favour with The Panthers (In 2003, Mario Van Peebles' played his father in his fictional account of the making of the film, Baadasssss.). With the notable exception of the Newreel film collective's documentaries Off the Pig, Mayday and, Repression, there was very little made about the Panthers in the US as the time. The job of documenting the Black Power Movement was largely left to European filmmakers, through films such as Chris Marker's magisterial 1978 film essay, A Grin Without a Cat, Peter Whitehead's masterpiece, The Fall (1969), and Agnes Varda's short 1968 documentary, Black Panthers. At its best documentary filmmaking challenges its practitioners, audiences and subjects, so, part of the fascination of Olsson's film lies in second-guessing the thoughts of the sympathetic Swedes who provided this footage. What, we wonder, were they thinking, as they recorded cultural and political circumstances remote from their experience?

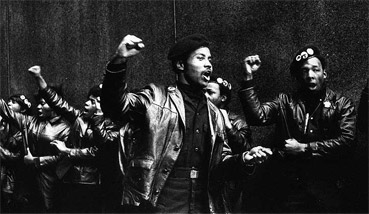

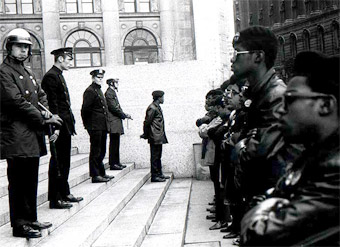

© rozpayne/newsreel collective

The Black Power Mixtape was shortlisted for the prestigious Grierson Award for Best Documentary at the London Film Festival and won the World Cinema Documentary Editing Award at the Sundance Festival. Olsson co-edited the film with Hanna Lejonqvist, who deserves special praise for what is, after all, a snapshot collage or fragmentary montage of found footage. He and Lejonqvist mix a series of mesmerizing archive interviews with contemporary commentary to present a compelling scrapbook of the Black Power movement. The archive footage focuses on prominent Panthers such as Stokley Carmichael (who is credited with coining the term "Black Power"), Elridge and Kathleen Cleaver, Angela Davis, Huey P. Newton, and Bobby Seale. The archive material is overlaid with audio commentary divided roughly equally between battle-hardened veterans of those revolutionary struggles – such as Harry Belafonte (pictured above with Dr King), Davis, the Cleevers and Bobby Seale – and also a young generation of musicians such as Erykah Badu, Talib Kwelli and Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson.

In taking on the challenging job of sifting, sorting, and selecting from the amazing raw material at his disposal, Olsson shies away from radical advocacy and seems to have allocated himself a primarily curatorial role. That in no way diminishes his achievement, for he has performed the kind of invaluable service so brilliantly undertaken by the curators of the British Film Institute and other such organisations. Having unearthed this treasure of unseen footage, he then stands back to let the images speak for themselves, allowing us to get on with the job of assessing and contesting what is shown. Given his subject matter, we might hope for more analysis, depth, and political bite and insight, but, fortunately, the found footage does most of Olsson's work for him. Various incredible scenes transport us back to those volatile times, showing us things we can barely imagine today. We see black schoolchildren in a Panther school chanting in unison: "Come on people, join the struggle. Pick up a gun. Put the pig on the run." We see sage Harlem Bookseller Lewis Micheaux, proprietor of the legendary National Memorial African Bookstore, dwarfed by walls of books, rhyming infectiously, and insisting, "Black is not power. Black is beautiful but knowledge is power." We see Louis Farrakhan, slippery and sly even then. We see Stokley Carmichael with the King of Sweden. We see Kathleen Cleaver in Algeria, at the Panthers' refuge abroad. The footage may be ordered rather randomly, and interspersed with annoying date inter-titles that flash up on screen too frequently, but it is still wonderful to watch.

That the reviews of the film have been predominantly positive is interesting in itself. This may tell us more about the longevity of white liberal guilt, the respect posterity affords to the valient vanquished, and about the persistence of radical chic at the expense of politics, than it does about the film itself. Lacking a feminist analysis, the Panthers' may have partly paved the way for Louis Farrakhan's particular brand of patriarchal, black-nationalist politics; they certainly retain an appeal for post-feminist admirers of virulent machismo. Regardless of their motives, reviewers have tended, rightly, to single out two particularly revealing and moving moments from among many in the film. In one scene, Stokley Carmichael takes the microphone from Swedish journalist Ingrid Dahlberg, as she flounders while interviewing Carmichael's mother, Mabel, at home. Carmichael then proceeds to interview her himself, dialectically drawing from his mother the true story of the difficulties his father, her husband, faced finding work due to racial discrimination. Just as Leila Doolan's film humanises Bernadette Devlin by showing her relaxed and at home, so Göran Olsson's film humanises the Panthers. Here, for instance, Carmichael is revealed to as he really was 'off camera': tender, gentle, proud yet respectful. Olsson has selected many similar moments that offer us glimpses of the Panthers in intimate 'off guard' moments, sharing a joke, laughing. It reminds audiences that the Panthers are people, yeah, just like you and me, and goes some way toward counteracting negative representations of them. It de-demonises them.

| Angela Davis and the Question of Violence |

|

© rozpayne/newsreel collective

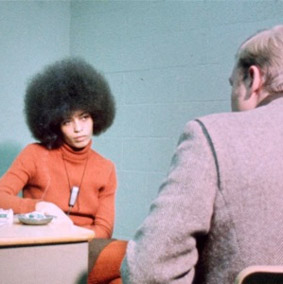

The second key moment in the film, perhaps its most important, occurs when a naïve Swedish journalist interviews Angela Davis in prison. He asks her a trite question about violence. She delivers the perfect response to those who have uncritically accepted representations of the Panthers as racist terrorists. When this incredible interview took place, in 1970, she was facing the death penalty for purchasing the gun that John Jackson used to seize Marin County courthouse, an incident that ended in Jackson's death and that of the judge he had kidnapped. Davis looks drawn and exhausted. We wonder how they are treating her, what they are feeding her and if they are allowing her sleep. Despite her haggard looks, she responds to the Swede's question with startled, almost stammered vivacity and indignation: "You ask me whether I approve of violence. I just find it incredible, because what it means is that the person who's asking that question has no idea what black people have gone through, what black people have experienced in this country since the time the first black person was kidnapped from the shores of Africa." She goes on to describe the scene of carnage that followed the 1963 bombing of a Baptist church in Birmingham, Alabama by the Klu Klux Klan, an attack that killed four black schoolgirls whom she knew personally. She talks, with contained anger, of "limbs and heads strewn all over the place." It is a stark reminder that the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence was born in 1966, in response to white vigilante violence, police brutality, and racist murder. Angela Davis' political savvy is equivalent to Bernadette Devlin's. Incredibly, Davis was incarcerated in New York at exactly the same time Devlin was serving her sentence in Armagh jail. Upon her release, Devlin she said: "I was involved with people in defending their area. They were justified in defending themselves and I believe I was justified in assisting in their defence." Angela Davis might have used those exact words upon her release. The parallels are striking.

There's another important moment that has passed most reviewers by unnoticed, one involving legendary documentary filmmaker Emilio de Antonio. De Antonio's 1964 documentary, Points of Order, which screened in the Archives section of the LFF, is a key political film of that era. It was anther highlight of the Festival. George Clooney gave us a fictional account of Ed Murrow's clash with McCarthy in his excellent Good Night and Good Luck, De Antonio gave us the real deal. In his film de Antonio presents a 'mixtape' of the 1954 Army-McCarthy hearing, packing 40 days of televised footage into a punchy 97 minutes. It contains the Army counsel Joseph Welsch's famous rejoinder to McCarthy, "Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?" Here, de Antonio is asked to comment on TV Guide magazine's politically charged accusation, in 1971, that Swedish journalists were 'anti-American' in their coverage of the US and in their dealings with the Panthers. Needless to say, de Antonio has no truck with that perspective, but the scene highlights how fraught relations were between Sweden and the US at the time. They had not improved markedly since 1960, when President Eisenhower launched a vitriolic attack on the Scandinavian country, claiming that "sin, nudity, drunkenness and suicide" were Swedish characteristics caused by their commitment to welfare state 'socialism'. The Black Power Mixtape draws extensively on Lars Ulvestam's film, Harlem: Voices, Faces, and when that film was screened on Swedish TV the US Ambassador there demanded equal airtime to correct what he said were 'flaws' in it. Astonishingly, he was granted leave to do so, but even that generous and gracious act of forbearance and tolerance did not improve matters. Soon afterwards, the ambassador was making his way back to Washington. The US severed diplomatic ties with Sweden, not for the first time, when Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme compared the bombing of Hanoi to that at Guernica, and to wartime SS massacres. Swedes – journalists and filmmakers included – had been politically energised by Palme's 'revolutionary reformism', which combined a domestic commitment to trade union rights and wealth redistribution with outspoken opposition to the war in Vietnam, the Apartheid regime, Franco's dictatorship in Spain, the Pinochet coup, and authoritarian regimes the world over. Palme's assassination in 1982 deprived the world of great statesman. His standing on the political left during the period the film covers helps explain why the Panthers were so ready to trust these Swedish journalists, and grant them open access to their lives and their movement.

It would be understandable if Olsson, both as a white European filmmaker and as a Swede dealing with Swedish footage about African-Americans, approached his subject with a double layer of self-consciousness and a deeply felt sense of caution. It is to be regretted that he didn't match the Panthers' political dash and daring with more formal invention. In their thought-provoking book Cinema/Ideology/Criticism, Jean-Louise Comolli and Jean Narboni divide political films into several categories. The category that most fits The Black Power Mixtape is the one in which they describe films that, "have an explicit political content . . . but which do not effectively criticise the ideological system in which they are embedded because they unquestioningly adopt its language and its imagery." It certainly feels as if Olsson is playing safe, but I suspect self-conscious caution had less influence on his selection of music and footage, and his choice of who to interview for the commentary, that did his determination to draw young audiences to the film. That might explain why the commentary is so politics-lite and why Olsson decided, regrettably, to focus on musicians at the expense of historians and political thinkers. His desire to reach young people is laudable, but, unfortunately, it does the film no favours, and the soundtrack certainly suffers for it too. Presumably it was Olsson's Philly Soul connection that drew him to The Roots, and there's something fitting about their R&B-tinged style that works, but, overall, the film cries out for something harder, funkier and more raw than it gets. I can't help regarding the soundtrack as a wasted opportunity to dovetail the found footage with music from that period, perhaps some protest songs from Soundtrack for a Revolution! Some rare groove soul; some James Brown, Isaac Hayes and Gill Scott Heron; and a radical dash of Public Enemy ("the Black Panthers of rap") would have spiced the 'mixtape' up. Public Enemy's 'Fight the Power' would been an obvious choice, but, call me old fashioned, I'd like to have heard Billy Holliday's 'Strange Fruit', Nina Simone's 'Mississippi Goddamm' or Lena Horne's 'Now' in there. Readers will have their own ideas. While the soundtrack is serviceable, it says something about it that I found the scene in which Stokley Carmichael riffs to Jimmy Collier's 'Burn, Baby, Burn' its most exciting moment.

If the film's soundtrack feels slightly flat, so, sadly, does its approach to politics. It is as if Olsson's evident emphasis on educating a new generation about their radical forebears had persuaded him to eschew difficulty and danger in favour of a stripped-down, bare-bones 'high school' history lesson. I've no wish to reprise ongoing debates about running times here, but, as I did in the case of Bernadette: Notes on a Political Journey, I wished the director had challenged concentration spans as boldly and effectively as political misconceptions. The devil is in the detail. There is no strong sense here that the Panthers were revolutionary socialists whose political worldview was shaped by Mao and Marx as much as by Malcolm X. The film contains no mention of the Red Book, which was compulsory reading for all Panthers, and informed their battle cry "All Power to the People." It completely ignores the relationship between the Panthers and other radical organisations, such as Black Power group US (nicknamed United Slaves by the Panthers), the American Indian Movement, and the Weather Underground – fortunately, Sam Green and Bill Siegel at least record the Panthers' willingness to work with white radicals in their 2002 documentary, The Weather Underground. There is little sense either of the importance to this generation of African American radicals of the bloodbath that prompted Huey Newton and Bobby Seale to form the Black Panther Party and less still of the bloodbath that contributed to the Panthers' fragmentation. Olsson's 'argument', roughly, is that the fight went out of the Panthers and their communities as the ghettos were carpet-bombed with drugs. There's much truth in that sociological take on those times, but internal divisions and, more importantly, the FBI's COINTELPRO campaign were equal factors in the reduction of the Panthers' strength, and a cause of their fragmentation.

| The Panthers and The Feds |

|

As Kathleen Cleaver says in The Weather Underground: "Once Richard Nixon was elected President and inaugurated in January 1969, we were targeted – bam, bam, bam – by a very sophisticated, advanced counterintelligence programme. At the same time, by very crude and violent police." It is impossible to gauge the extent to which the FBI penetrated the Party, but there's no question that every invented technique of sabotage was used against the Panthers: bombings, disinformation, forged letters, harassment, infiltration, informants, intimidation, 'provision' of drugs, psychological warfare, smears and, ultimately, assassination. The split between Stokley Carmichael and the Panthers was a clear-cut case of ideological and strategic differences, with Carmichael disapproving of the majority decision to work with white radicals, but the split between Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton was nothing more than a power struggle massively exacerbated by the COINTELPRO destabilization campaign. The FBI exploited existing divisions within the Black Panther Party as efficiently as they did divisions within the Black Power Movement, most significantly by stirring up animosity between the Panthers and US. As Martin Luther King said: "Whenever Pharaoh wanted to keep slaves in slavery, he got them fighting among themselves."

David Leaf and John Scheinfeld's 2006 documentary, The US vs John Lennon – which shows the extent of Lennon's friendly relations with Angela Davis, Bobby Seale and the Panthers – reveals how even a figure as comparatively innocuous as Lennon was targeted by the FBI. Many of the covert, illegal, and strenuously denied tactics deployed by the FBI against Lennon, Dr King, the Panthers and other radical groups were exposed by the Church Commission in the wake of Watergate. Meanwhile, the agency's claim that covert counterintelligence operations are a thing of the past is exposed as a lie in Kate Galloway and Kelly Duane de la Vega's documentary, Better This World. This film reveals how two naïve, impressionable activists were caught up in the post-9/11 paranoia of the US security apparatus, after being persuaded to prepare Molotov cocktails for use at the Republican National Convention in 1980 by Brandon Darby, an egotistical former activist turned FBI informant and provocateur. It is a classic case of entrapment, the creation of scapegoats to scare others away from political action. Ireland's experience of similar 'dirty tricks' – collusion, internment and the 'Shoot to Kill' policy – were, of course, dealt with effectively by Ken Loach in Hidden Agenda. I won't labour the obvious comparisons between COINTELPRO activity in the US and that of MI5 in Ireland, suffice to say that the splits within the Republican Movement and the often violent spats between Republican splinter groups were equally well exploited by security forces well versed in their tried and tested 'divide and rule' strategy.

Neither state nor black-on-black violence has any place in The Black Power Mixtape. This may be because it didn't feature in the material Olsson selected from. It is possible that none of the Swedish journalists reporting on the Panthers were aware of divisions with the Black Power Movement, but they could hardly have failed to be aware of the FBI assassinations of Little Bobby Hutton, Mark Clarke, Fred Hampton and others, even if they hadn't seen Howard Alk 1971 brilliant documentary dissection of an FBI assassination: The Murder of Fred Hampton.*** It may also be that Göran Olsson's deliberately set aside consideration of violence and division within the Black Power Movement, for fear of confirming widely held prejudices and misconceptions. That would be understandable, even admirable when viewed from a certain perspective, but it would not explain why the film equally downplays the virtues of the Panthers, their practical politics, their commitment to community service, and the positive example they set within their communities. There is little attention paid to the "Breakfast for Children" or free meals programmes, the Panther medical centres and schools, or The Black Panther newspaper, which had a weekly circulation of circa 140,000 at its peak. The Panthers' sense of discipline and positive code of conduct is passed over too; it's insistence that members forego drink and drugs, that they must never, " . . . take a single needle or piece of thread from the poor or oppressed masses," nor point a gun at anyone or use it accidentally. The film's assorted sins of omission result in a compelling but unbalanced, slightly sanitised view of the Panthers.

Towards the end of the film; as shimmering black and white footage makes way for muted, faded, autumnal colour; as the utopian optimism and revolutionary energy drains out of the embattled, war-weary Panthers; Ollson inserts the film's keynote scene, an interview from Harlem: Voices, Faces. A tearful young woman, hunched in the darkened doorway of a brownstone, describes her personal struggle with drug addiction and her desire to leave behind the life of prostitution to which she has been reduced. The scene is harrowing, heartbreaking and angering. She stands in for all those left behind – unrepresented, voiceless and hopeless – by the Panthers' demise as a political force and the collapse of the political possibilities they proposed. She represents the human cost of the social circumstances against which the Panthers fought, that contributed to their demise, and that have worsened in their absence. She symbolises, not an isolated example of individual fecklessness, but, rather, the towering pile of human misery on which the status quo is built. Her presence in the film points an accusatory, metaphorical finger at gross inequality, acting as a cinematic détournment of the iconic First World War recruitment poster featuring Lord Kitchener, rephrasing his demand for sacrifice as, "Your Fellow Human Beings Need You."

The Black Power Mixtape and Bernadette: Notes on a Political Journey educate and enthral us. They might even embolden and encourage a new generation of the enraged to pick up the torch of justice, and begin again where the Panthers and Bernadette Devlin left off. These films certainly remind us of the colossal challenges and forces faced by those inclined to 'fight the power'. They also remind us that, as Walter Benjamin pointed out, revolution is not a runaway train but, rather, the emergency breaks. They record the political heritage we inherit. Two former Panthers – Huey Newton's widow, Fredrika Newton, and David Hilliard – recently reminded us of that heritage too. They have latched on to the aura of radical chic surrounding the Panthers to market a spicy condiment, 'Burn Baby Burn Revolutionary Hot Sauce' – all in a good cause, of course. It would be funny, if the tastelessness and cynicism it represents were not so depressing. In his memoir, The Gatekeeper, cultural activist and Oxford don Terry Eagleton says: "A left-wing friend of mine, when stopped on the street by someone rattling a can for charity, is in the habit of peering suspiciously at the label on the tin and asking gruffly: 'Is this a Marxist organisation?' When warmly assured that it is not, he waves his hand dismissively, says, 'I'm sorry, in that case I can't contribute', and passes on." We can but wonder what Eagleton's comrade would make of those cynical, saucy ex-Panthers. Those of us who believe we owe a debt of gratitude and respect to those featured in these films will take that heritage forward in more fitting ways. In doing so, we should strive to live without illusions and without becoming disillusioned. As Victor Serge says, in The Long Dusk: "What is more natural and inevitable than to be beaten, to fail a hundred times, a thousand times, before succeeding? How many times does a child fall before learning to walk? The main thing is to have strong nerves. Everything depends on that. And lucidity . . . Human destiny will brighten."

<< PART 1

|