| |

"I came from a family who believed in, in quotes, the 'Rights of Man', who believed that in order to justify the sort of luxurious life that the majority of us have, related to the whole world, that you had to do something." |

| |

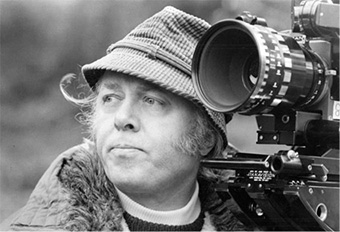

Richard 'Dickie' Attenborough, CBE |

| |

"Richard Attenborough is by far the finest, most decent human being I've met in the picture business." |

| |

William Goldman, Adventures in the Screentrade |

Here was a man who recognised how lucky he was, how privileged he was through accident of birth and circumstance and spent his life giving back to the world. It's no secret that the Thomas Paine book he insists is in quotes ('Rights of Man') is a tome to live by. And Attenborough pursued giving back with a zeal few could match. Yes, he's known to this site as a filmmaker first, actor second and activist third but drawing a line between those activities is to miss the point. His activism was his filmmaking too. He admitted that he only read classic fiction being more interested in the world of real and great people and their real effect on the collective global consciousness and the way their lives changed the world. One look at his credits as actor and director and the themes start to emerge; there is a profound interest in people who have shaped the world (Gandhi, Churchill, Chaplin); there is a great variation in his many acting credits and I find it wonderfully ironic that one of the nicest men (and I use the word 'nicest' with no hint of sarcasm) in the industry got his acting break playing an amoral thug, Pinkie in the classic Brighton Rock.

Attenborough wore his enormous heart on both sleeves and was given to emotion at the drop of any sort of headgear. Can you imagine what kind of a wreck he was in his hallway in 1976 getting two letters from Downing Street informing him that he was being offered a peerage and the place of a Trustee for the Tate Gallery (something he dearly wanted)? He had to call his wife Sheila Simms to confirm what he was reading. It didn't take long for the outside world to brand him the Luvvie's 'Luvvie'. To those unfamiliar with the term, it's mostly derogative and refers to an actor who imbues his or her work with more significance than it might merit. A Luvvie is also somewhat affected. Eric Idle's Python take on him as simpering and effusive is to miss the strength and purpose hidden as it was behind a screen of such unforced bonhomie. You don't produce and direct Gandhi without a steel resolve. Yes, he called everyone 'Darling' but this was more to do with a failing memory than Luvviness. Whenever I hear the name 'Attenborough', I keep thinking of David, Richard and John's mother, Mary sitting open mouthed in her living room at the extraordinary success of her three boys (David's path in the world needs no further comment. John was an Executive at Alfa Romeo).

Most of all, from a personal perspective, one of his films helped me to define what kind of film I wanted to make when I was emerging from the buffeting currents of youth. So many of my friends place me squarely in the nerd box (fair enough). I was 16 when I saw Star Wars, exactly the right age to be seduced by the Force but my tastes weren't as narrow and wanting to be a filmmaker with no clear idea of what films I wanted to make troubled me for a long time (what kind of a film could a virtual child make that said anything about the human condition interesting enough to make a film about?) Nerd passion is its own reward "Ooooh! Spaceship!" Saying something meaningful has to wait until you've lived a little. In 1978, Attenborough directed Magic, a curious thriller about a magician whose failed career turns him towards ventriloquism where he finds some success as well as a worsening psychotic breakdown. Based on a novel by famed screenwriter William Goldman, Magic featured a wonderful cast. Anthony Hopkins was young, devilishly good looking and had been off the sauce for three years. He played the disturbed Corky with an intensity that was incredibly unnerving. The gorgeous and underrated Ann-Margaret was his childhood sweetheart now married to a man who loved her but couldn't be whom she needed. Burgess Meredith (Rocky's manager and ex-Penguin) played Corky's agent. The scene of him asking his client to shut Fats (the dummy) up for five minutes is seared in to my memory.

I came out of that bittersweet and sometimes terrifying movie with an 'Aha!' moment. You could make movies that simply satisfied with wit and integrity. As long as you made your film with passion and gave it your all as a filmmaker, you could make worthwhile movies with no great profound statement on the human condition necessary. In my small and insignificant opinion, this is where Spielberg forked up. He had achieved great success doing the former - just entertaining. He then regarded his place in the pantheon, a fork in the road, and started making 'worthy' films he believed he ought to be remembered for. Attenborough was naturally good with actors being one himself and went to great pains to draw out performances from actors with very different working methods. While some directors, faced with chalk and cheese in clashing styles, would throw up their hands in frustration, Attenborough was canny enough to work as chalk with chalk and as cheese with cheese and bring them together when both were firing. This was certainly the case in his work on a film he was 'least embarrassed by', Shadowlands.

One final story featured in the afore mentioned William Goldman's memoir, Adventures in the Screentrade and I'm paraphrasing from memory. Attenborough (54 at the time) was shooting A Bridge Too Far and as ever, time and weather wait for no man however well intentioned. Goldman was present when he saw something remarkable. Attenborough (the director, a role usually cosseted while in production) picks up heavy film gear and schlepps off to the next location. This is the equivalent of Humphrey Bogart picking up the tripod and walking over to the next soundstage. It was never done. Directors simply did not do this. That is and sadly was Attenborough to a tee. His singular humanity will be missed as much as his filmmaking talent.

I already have an image of Attenborough in heaven and in my own godless way, I hope he's smiling when he gets there as he did as the amazed airman in A Matter of Life and Death, the Archers' finest movie and Powell's own personal favourite. If anyone deserves his wings...

I never met Richard Attenborough, but once came close. I was charged with transporting a group of film students across central London to a special preview screening of Grey Owl, one of the very few Attenborough directed films I actually don't much care for. But that's beside the point. Despite claiming I knew my way around this part of the capital like the back of my hand (which I'm actually not that familiar with, if the truth be told), I managed to get us lost, and the screening was already well under way when we arrived. (It's worth noting that in the process of getting there, we almost bumped into Mike Leigh – this was a great day for nearly meeting British filmmaking greats.)

The film was attended by a rowdy audience consisting entirely of school and college students, most of whom probably didn't really want to be there and were making no secret of it. But when the film concluded and the noisy buggers departed, the rest hung around and shuffled to the front for what for us was the principal reason for travelling all the way to London in the first place. Moving slowly and aided by a walking stick, Richard Attenborough himself then walked onto the stage to talk about the film and answer questions from the enthusiastic students who remained. And he was an absolute delight, a hugely entertaining speaker who joked about his equally famous brother ("He's the shorter, fatter one") and answered every question thrown at him with honesty and good humour. It was on my way out that I came closest to meeting him, but the way was barred by a five-person deep ring of excited schoolchildren who had him surrounded and looked set to engulf him. Despite his age and physical frailty, he was coping just fine with a level of boisterous energy that would have frankly left me wheezing.

By this point in his career, Attenborough had made a significant impact on me both in front of and later behind the camera. There's actually a chance that the first film of his I saw was the first one he made, Noel Coward's war drama In Which We Serve. Thanks to my father, I saw of lot of British wartime films on TV when I was a child, but this one left its mark because it dared to suggest that not everyone would show fortitude under fire, that for some the heat of battle could prove so terrifying that it could prompt them to desert their post and shock them into silence. And when it happened here, the man in question was not punished by his Captain, who clearly understood what he was going through. The wide-eyed, baby faced seaman in question was played by drama school graduate Richard Attenborough. It was his performance, more than those of any of the established names in the film, that I remembered most clearly later.

His role as Pinkie Brown in John Boulting's seminal adaptation of Graham Greene's Brighton Rock thus came as a bit of a shock. How could this almost child-like victim of the horrors of battle make for such a terrifyingly villain? Even as a boy, I was learning about the difference between an actor and a great actor. In the years that followed I was treated to Attenborough's talent for unforced comedy in Private's Progress (John Boulting again) and Basil Dearden's The League of Gentlemen, and his ability to exude an air of friendly authority as Captain Bartlett in The Great Escape. But the role that came to haunt me, the one that still today stands as an object lesson in low key malevolence, was his role as true-life serial killer John Christie in Richard Fleischer's extraordinary 10 Rillington Place. Seriously, if you've never seen this, hunt it out immediately. It's a performance that genuinely chills the bones.

By this point in his career, Attenborough had already turned his hand to directing, having formed his own production company, Beaver Films, with his friend and fellow actor-turned-director Bryan Forbes in the late 1950s. Actually ‘turned his hand' sounds appallingly condescending, given that for his first film as director he took on the monumental task of transforming Charles Chilton and Joan Littlewood's anti-war musical Oh! What a Lovely War (aided by a screenplay by none other than novelist Len Deighton) into a cinematically ambitious and star-studded feature film.

A lifelong member of (and campaigner for) the Labour party, his strongly held belief in social justice and equality led to two of his most celebrated films as director, Gandhi and Cry Freedom. Both films have survived some initial controversy – Gandhi for the casting of a non-Indian actor in the central role, Cry Freedom for telling Steve Biko's tragic story from the perspective of a white reporter – to become widely acknowledged classics that have been praised from bringing their stories to an international audience. And their scale is sometimes breathtaking – the funeral procession at the start of Gandhi remains to this day one of the largest scenes ever staged for cinema involving real participants rather than computer generated crowds.

But for all his many achievements I remember Attenborough primarily as one of the nicest people every to grace the British film industry, a gentleman with a social conscience whose cultured diction could transform even crudities into something rather delightful. My favourite example of this was in a TV documentary shot on the set of one of his features (I wish I could recall which), when he was observed by the camera, probably unaware, as he spoke to two friends who were visiting the set. "If I don't get a nap in the afternoon nowadays," he told them in the most polite of voices, "I'm absolutely fucked."

Goodbye Richard. And thanks for everything.

|