|

Ten years after his imperishable fiction debut, Silence; six years after his poetic biopic Song of Granite; and many magnificent documentaries later, Pat Collins is back. That They May Face the Rising Sun, a pitch-perfect adaptation of John McGahern's great final novel, is an achingly tender and richly textured portrait of a year in the life of a close-knit Irish farming community. It is a delicious slice of slow cinema with healing properties. To leave the cinema after seeing it is to return, reluctantly, to the chaos, commotion and jarring clatter of modern life after a restorative stay in a hushed haven of tranquillity. After our year in the country, we return to our frantic lives refreshed, wondering what we might be missing out on in our frenetic headlong rush through time and what we might gain by fashioning less febrile, better balanced lifestyles for ourselves.

That They May Face the Rising Sun opens with a two-minute shot of the sun gradually rising through dappled clouds over a shimmering expanse of water. That exquisite sequence establishes a feeling of unhurried calm from the start. The film proceeds to provide us with an invaluable cinematic space in which to take stock of our own lives while watching the lives of others unfold before our mesmerised eyes. Lily Tomlin says, 'For fast-acting relief from stress, try slowing down.' This enchanting film helps us do so. Though earthed in one particular isolated place, where nothing much happens – except everything, this deceptively simple film contains all the love and loss, hope and harshness of life. It operates as both an encomium to a fast-disappearing ancient way of life and a stinging rebuke to our own shrill, money-mad and hasty times.

Joe (Barry Ward) and Kate (Anna Bederke) Ruttledge long ago left London behind for County Leitrim and the lakeside community near to which Joe grew up. What, Pat Collins seems to ask, did they gain by swimming against the tide of Irish emigration? A landscape of exquisite elemental beauty, the continuities and satisfactions of farming, a serene existence attuned to nature's rhythms, independence, neighbourliness, stillness, togetherness, something approaching complete happiness. They seem content and fulfilled. They work from home. Joe writes. Kate paints. They cultivate bees, grow vegetables, rear sheep, make hay while the sun shines. Their door is ever open and neighbours stroll through it – to be welcomed with a smile, a cup of tea, often a nip of Paddy's or Powers.

Among the couple's frequent visitors are Joe's avuncular uncle, nicknamed 'the Shah' (John Olohan), farmer Jamesie Murphy (Phillip Dolan), orphan Bill Evans (Brendan Conroy), garrulous odd-job man Patrick Ryan (Roddy Lalor), and, when he's home on leave from Ford's in Dagenham, Jamesie's brother Johnny (Sean McGinley) – symbol of the diaspora. These few intersecting, interwoven lives stand in for rural Ireland as it was half a century ago and for the whole wide world beyond. The emphasis in both novel and film, though, is firmly on the local. As John McGahern said, 'One room can become an everywhere but if you start with the universal or the everywhere you get a nothing . . . everything interesting starts with one person and one place.'

Collins says the source novel was always his favourite among McGahern's books, and the only one he'd been tempted to adapt. He told the BFI's Georgia Korossi, 'I don't think I would've been able to do it until now, at the age of 56. I know it's kind of crazy, but I think I needed to have a certain amount of work behind me before making it.' The technical expertise Collins has honed during a remarkably fecund career spanning 25 years and over 30 films is, of course, a vital part of what That They May Face the Rising Sun tick. As is a superb ensemble cast, each of whom bring each of McGahern's vividly-drawn, quietly compelling characters bursting into glorious life.

Barry Ward, having most screen time, inevitably sets the tone with his sensitive, quietly compelling portrayal of Joe, but the entire cast are flawless throughout. All deliver performances of understated subtlety, suggesting a happy set Phil Donnell's quietly commanding performance as farmer Jamesie Murphy deserves special mention. Collins stumbled upon Donnell in a pub, was immediately taken by his skills as a raconteur, and took a gamble that paid off handsomely in casting him.

As the film's rich cast of characters come and go, Collins and co-writer Eamon Little gradually reveal a rich ecology of organic mutual aid. Jamesie teaches Kate the art of basket-weaving. His wife Mary teaches her how to pull wool and weave. Patrick intermittently helps Joe construct a shed that may never be finished. There's no hurry. We are social beings, born to share life with others, so they share the joy of living and the shed can wait. Everyone pitches in at harvest time though. Everyone knows what needs to be done. Everyone pulls together, too, when death comes calling. They know their place, the land they love and work within, bound to it and bound to one another by it as they are.

In his 2014 essay film on colonisation and the Irish Midlands, Living in a Coded Land, Collins quotes from the 1974 documentary Wheels of the World/Rothaí An Domhain: 'The people grow into the image of the country and the country grows into the likeness of the people till, to the soul's geographer, each becomes a symbol of the other.' Much, perhaps, as a dog can come to resemble its owner, and vice versa. The two-way, mutually beneficial relationship between the land and its people runs deep. It is far more complex and longstanding than the condescending contemporary cliché that has landscape as 'a character in the film' suggests – a comment commonly found in reviews of films like Martin McDonagh's The Banshees of Inisherin.

While McDonagh's film refers back to the kind of rural Ireland landscapes Patrick Kavanagh looked back on in Tarry Flynn, it also glances forward to those alluded to by Ernie O'Malley in On Another Man's Wound when he said, 'A harsh land and lonely, hard to make a living from its grudging soil, cruel hard they said it was, as hard as the hob of hell, and desolate in the winter.' Collins shot That They May Face the Rising Sun in summer, so gale-force winds are no more present in the film than drought, floods, storms, crop failure, soil erosion, animal diseases or any other of the catastrophes feared by farmers. The dominant sound in the film is birdsong not driving rain. Cinematographer Richard Kendrick expertly picks out glittering or muted greens, but no black clouds darken the screen. No matter, the look and feel of landscapes may change with the weather, but they are largely unchanging. As James Joyce said, 'Thirty years in the life of a mountain is nothing, the flicker of eyelid'.

The social circumstances veiled by landscape, meanwhile, alter enormously. Landscapes, as John Berger suggests in A Fortunate Man, are deceptive: they can act as a curtain behind which human struggles unfold, a curtain obscuring poverty and loneliness. When Bill Evans visits the Ruttledges, he always carries with him two buckets; lacking water at home he must draw it from the nearby lake. When Joe visits Patrick at his tumbledown bachelor den, we realise that his odd jobs don't pay well and cannot help but fear for his health in winter. The film's lilting soundtrack intensifies the piquant melancholia our glimpse behind the curtain evokes.

For those behind Berger's curtain, landscapes and landmarks are not only geographical, as they are for us, but deeply biographical and personal too. Elsewhere in Wheels of the World, narrator Eamonn Keane says, '(This) is a land that for generations was tended with an infinity of energy and skill by a people to whom every field and tree and rock and stream had its own being. A people who knew the land because they wooed it intimately – with hand ladle, with a spade and a fork and the reaping hook and the scythe. A world that except in fragments has gone unchronicled and unmirrored. That has fallen over the cliff of silence.' First John McGahern, now Pat Collins, in their respective forms, have countered that particular silence with moving, measured testimony to the human solidarities of those who inhabit the landscape and work the land.

By eliding the darker aspects of rural life and by excising some of the darker characters in McGahern's novel (the misogynist Joe Quinn, local IRA leader Jimmy Joe McKiernan), Collins pares things back to the positive. By doing so, he reminds us how smart, complex and witty such so-called 'simple farming folk' can be and how rich rural life is despite its slicing shards of penury. He depicts a self-sustaining community that comes together when celebration is in order (as it is at Christmas or when The Shah marries) and which moves as one when the need arises (as it does when first Patrick's brother, Edmund, and then Jamesie's brother, Johnny, die). Its members support each other through thick and thin, through good times and bad. This is an effective coping strategy as surely as those rites and rituals developed down centuries. Their very language is peppered with folk aphorisms, with what was once called 'the people's wisdom' – for hard graft and hardship have taught them life's lessons well. To call this 'homespun philosophy' would be condescending too; they have a deep-rooted understanding of life that flows from experience and from their working relationship with nature.

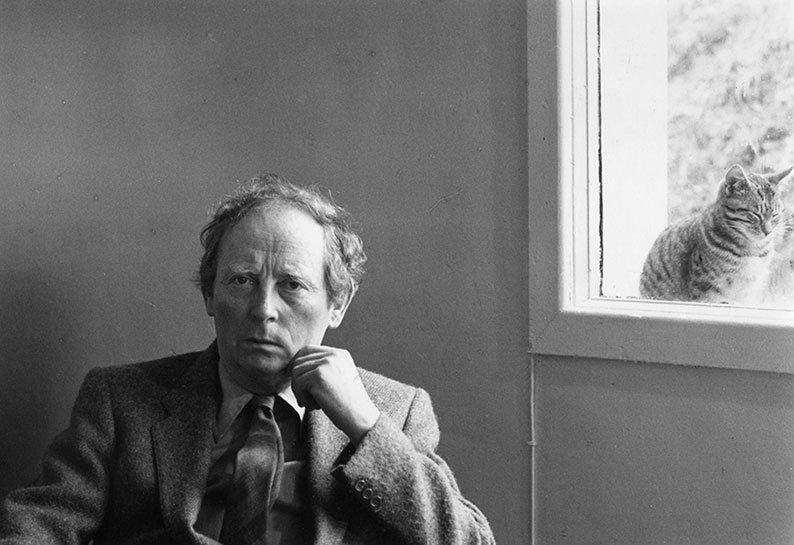

John McGahern – photo by Madeline McGahren

After telling Joe he's considering selling the garage he owns, the Shah gazes across the lake at the mountains and says, 'The rain comes down, the sun shines, the grass grows, children grow old and die, that's the holy all of it. We all know it full well but can't even whisper it.' That is McGahern himself speaking, from the heart, although he himself said it out loud. In an interview that features in Collins' 2004 documentary John McGahern: A Private World, he says, 'The life where nothing happens, among the dear familiar things, is for me the most precious life, and all we have is the precious moments and the hours and the days.'

When Kate receives an offer to return to the London gallery she has a stake in, she tells Joe she feels they're still just settling in and living from day to day. Joe asks, 'But isn't that the beauty of it, the living day to day, just doing the work? Isn't that why we came here?' Patrick's not so sure. When he and Johnny discuss them fondly, he says, 'They say what keeps them here is the quiet and the birds. Listen to the feckin quiet and see if it wouldn't drive you daft!' The Ruttledges relationship to the place is not what it is for those firmly anchored there by more pressing needs.

As Seamus Deane says in his penetrating review of the source novel upon its release in 2002, it was only partly a novel because it was also part meditation, part memoir, part retrospect, part anthropological survey, and the culmination of a lifetime's acquired skill and knowledge. Much the same could be said of Pat Collins's film. Although Collins hails from West Cork rather than the Leitrim-Roscommon border area in which McGahern was raised, he grew also up in a rural community, among people similar to those the writer castegated and celebrated. McGahern knew that of which he spoke. Collins knows that of which he speaks. The challenge of adapting a novel as subtle, as alive with thought and feeling as McGahern's called for such a unique combination of attributes that it's hard to imagine anyone better equipped for the job than Pat Collins.

Perhaps, above-all, it is Collins' intimate knowledge of McGahern, their shared subject matter, and the contiguities linking them that underpins the film's success. He had more reasons than most to appreciate McGahern's extraordinary gifts, having spent long periods in the writer's company while making A Private World. His first contact with McGahern was fortuitous: his sister studied English under McGahern in Galway, and he and his brothers worked their way through the reading list McGahern set her in their youth (including Ernie O'Malley's above-mentioned book).

Discussing his film on Henry Glassie with Korossi, Collins says, 'I think filmmakers should have patience and reverence.' All his films are manifestly marked by those qualities – which are reflected in their intimacy and stillness, in his close attention to detail and sustained concentration. From its opening moments, That They May Face the Rising Sun is imbued with a sense of quiet intensity or languid intentness, a kind of active placidity and open receptiveness characteristic of Collins' cinematic sixth sense and subtle signature style – more often associated with found footage and judicially selected citation; here, replete with his capacity for telling pointillist character study.

Patience and reverence underpin even Pat Collins' short films of 2017 Twilight and The Sea. Of the former; which was shot over two years on dozens of different evenings, close to his home in Baltimore, Co. Cork; Collins he says, 'It's not that I'm a perfectionist, far from it, but I think I enjoyed the experience of filming so much that I didn't want to stop – absorbing the light and the way sound changed.' Of the latter, he says, 'I wanted it to feel as if the world were taking long deep breaths and we were breathing with it.' We breath deeply as we watch That They May Face the Rising Sun. It is an invigorating breath of fresh air and we gulp it in greedily.

Every aspect of the film's creation knits together the fabric of rural Irish life and Collins's own directorial strengths to make a snug but sturdy Aran sweater of a film. The warp and weft of it are made from many materials. To mention but a few among the many, there is the nuanced grasp of history Collins demonstrated his essay films What We Leave in Our Wake and Living in a Coded Land; the knowing appreciation of literature evident in Michael Hartnett: A Necklace of Wrens (1999) and Frank O'Connor: A Private Life (2003); the love of cinema that shines through in Abbas Kiarostami: The Art of Living (2003); the love of nature that informs The Sea and Twilight; the profound sense of place on display in Tim Robinson: Connemara (2011) and Silence (2013); the acute awareness of folk tradition seen in Henry Glassie: Field Work (2019), and Song of Granite (2017); and the commitment to collaborative creative practices in The Dance (2021). These are just some of the elements that help make That They May Face the Rising Sun so beautifully balanced, so lyrically potent, poised, and finely judged.

As that quick, incomplete dash through Pat Collins' impressive and growing body of work might suggest, he has always straddled the blurred line dividing fiction and documentary. He did so most obviously while writing Silence and Song of Granite with his partner Sharon Whooley. Their scripts for both films seamlessly stitched together actuality with fabulation, and they are currently developing a film with the working title 'The Aran Islands', based on Synge's journals of the same name. It's hard not to speculate upon how closely the couple's lives in West Cork resemble those of the Ruttledges in That They May Face the Rising Sun. Tittle tattle, perhaps, but any such similarity would add another pertinent detail to the film's experiential authenticity and help explain why Collins has such affinity for McGahern's autobiographically charged work.

Pat Collins has done copious justice to McGahern and his majestic novel, to the community and way of life both he and McGahern represent with such nuanced reverence, and to Ireland herself. The Irish Times placed Silence and Song of Granite in its top twenty Irish film of all time. They may have to amend that list to lever That They May Face the Rising into it. This visually ravishing film is a sight for sore eyes and it quiet tenderness is soothing balm for stressed souls. In 1782, the poet William Cowper wrote, 'The tide of life, swift always in its course/May run in cities with a brisker force/But nowhere with a current so serene/Or half so clear, as in a rural scene.' By transporting us to rural Ireland, Pat Collins reminds those of us who live in cities, not only of the sacrosanct beauty of nature but of that essential sense of community we have largely lost.

|