|

When history shifts gears and the terrain changes, said Stuart Hall, you better believe you’re in a new moment and that there’s no turning back. The Pinochet coup that defenestrated Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government in 1973 was just such a pivotal moment. Having eviscerated democracy, Chile’s fascist junta consolidated its iron grip on power with a barbaric spasm of state terrorism that would soon spread screams far beyond Chile’s borders. With the assistance of CIA-trained death squads, many thousands of people were murdered and disappeared without trace across Latin America. Meanwhile, the neoliberal master plan set in train by the Chicago Boys in the ‘laboratory’ of Chile began its dirty work of increasing inequality, immiserating millions, wreaking environmental devastation, and even, ironically, establishing the risible notion that capitalism and democracy are indivisible.

There is a haunting moment in Chris Marker’s monumental film A Grin Without a Cat when, immediately after footage of Allende addressing workers, we see his pale, disconsolate daughter, Beatriz ‘Tati’ Allende, addressing a vast crowd in Havana. Speaking just weeks after her father’s suicide, she says, ‘From this free territory of America, we can answer the Comrade-President. Your people will not waver. They will not let down the flag of revolution. The struggle against fascism has begun. It will only end in the free, independent, socialist Chile for which you gave your life’. One of the film’s narrators (Yves Montand perhaps) then gravely notes that Tati Allende herself committed suicide in October 1977. We cannot know what drove her to take her life, but one factor must have been the assassinations of Miguel Enriquez (with whom she worked closely on Allende’s security), Orlando Latelier (a close family friend), and countless of her comrades in MIR (the Movement of the Revolutionary Left). She is often unfairly remembered ‘merely’ as Allende’s daughter, but she was an extraordinary woman and significant historical actor in her own right, a vital conduit between Popular Unity and MIR, a dedicated surgeon, and a committed revolutionary who resisted the gender norms of her day.

In A Grin Without a Cat, Marker moves on from that sad, unforgettable scene featuring Tati Allende to the testimony of an equally sorrowful young Brazilian woman, who describes the internal tortures suffered by her captured female associates. If she is still alive today, one imagines she must be in her 60s and that she’ll have celebrated Bolsonaro’s departure with relish and perhaps a few slugs of Caipirinha. Taken together, Manuela Martelli’s taut thriller 1976, Santiago Mitre’s courtroom drama Argentina, 1985, and Patricio Guzmán’s gentle documentary My Imaginary Country, help us join the historical dots. They enable us to draw a direct line from the bombing of La Moneda on 11 September 1973, through the CIA’s Operation Condor destabilisation campaign of the 70s and 80s, to the election of an unhinged neofascist, climate-change-denying, misogynistic misanthrope to the Presidency of Brazil in 2018, and beyond that to his removal from office last weekend.

Jair Bolsonaro’s contempt for democracy was laid bare by his nostalgia for the military dictatorship, just as his contempt for women was revealed by his assault on Vera Magalhães. Once a military man himself, one suspects he’d have liked nothing better than to declare the election results void, call out the army, and, who knows, perhaps even to begin hunting down leftist opponents. History does repeat itself, which is one of the reasons watching these films in close proximity at the London Film Festival sent a shiver down this reviewer’s spine, albeit one less than half as intense as the judder previously triggered by the passing thought of Bolsonaros’ re-election. With Lula’s narrow triumph in the election, disaster has been averted and the course, we can hope, is once again set on hope.

In 1976 (Chile 1976 in the USA), Manuela Martelli relegates the sadistic violence of the Pinochet regime to the margins, the better to render the paralysing pervasive terror that seeped deep into the bones of Chilean society. Fear eats the soul of Carmen (Aline Küppenheim), the bright dissatisfied bourgeois hausfrau at the heart of the film – a woman caught between the intimidating menace of dictatorship and the deadening, equally stultifying stranglehold of patriarchy. A consummate actress herself (she played opposite Rutger Hauer in Il Futuro), Martelli had no hesitation in casting Aline Küppenheim in the lead role. It was an inspired casting decision. Küppenheim’s superby controlled performance and inscrutable face give little away, so audiences are left to draw their own conclusions about what Carmen’s innermost feelings might be.

We first meet her in a paint shop, seeking the perfect pink for her family’s seaside villa, which she intends to renovate and redecorate. As an obliging worker adds deep blue and blood red emulsions to the mix, the sounds of screeching tyres and muffled screams drift in from the street. Curious, Carmen leaves the shop to find a woman’s shoe beneath a car. An atmosphere of dread and tension is immediately established. This mood is intensified throughout the film by Mariá Portugal’s thrumming-throbbing seventies-synth-laden score, by drips and drops of paint, and by the recurring motif of surging oceanic waves pounding rocks. Even the family’s coastal retreat itself may not be the haven Carmen hoped it might be. Two workers helping with the renovation speak in lowered voices about a local who was picked up by an army patrol and then disappeared. There is no escape, Martelli seems to say, from the claustrophobic, deliberately designed chaos and arbitrary violence of a tyranny that ensnares and entraps everyone.

The local priest, Father Sanchez (Hugo Medina), entreats Carmen to nurse Elías Nicolás Sepúlveda), a wounded fugitive he’s hiding, back to health. She reluctantly agrees to help, tends the young man’s shattered leg, and deploys cunning and subterfuge to secure antibiotics for him. When he openly confesses that he’s a political combatant on the run, she not only continues to help but takes increasingly dangerous risks to do so. She surreptitiously visits another priest in a nearby shanty town to arrange a new safe house for Elías. She even risks a meeting with one of Elías’s comrades in her efforts to help him. This may result from common and garden human kindness and sympathy or it may be a sign of her growing political awareness. Be that as it may, the net of state surveillance closes in on her as the film progresses. To the obvious pleasures of intensifying Hitchcockian suspense, then, are added those of a deftly crafted, completely compelling character study of appreciable depth and mystery.

When her family finally arrive from the city to join her, we learn that Carmen’s husband, Miguel (Alejandro Goic), is a doctor in league with the military regime. We wonder how much Carmen, cossetted as she is, really knows of contemporary political realities, and where her shifting loyalties lie. That is, until a revealing moment during a boat trip late in the film. During a conversation between her husband, his boss and her daughter, she first blanches when her daughter shrilly complains that the hospital where the men work is full of communists and parasites, and finally vomits when the men describe the kickbacks they take for services rendered. Has she always known, we wonder, and has the guilt of her supressed knowledge always tormented her? Or is she merely overcome by sudden revulsion for her daughter, her husband and her life?

Martelli offers several suggestive, if inconclusive clues. Carmen’s addiction to cigarettes and tranquillizers certainly suggests she’s contending with forms of angst and depression. Her psychological fragility is also hinted at in a telling scene during which Carmen huddles with her daughter and grandchildren to watch Super8 home movies of a family holiday. When Carmen’s daughter, Leonor (Amalia Kassai), says it was a sad holiday, her granddaughter wonders why. ‘I went crazy’, Carmen says, ‘and took off’. Her depression must, we realise, have predated the dictatorship and have roots in her unfulfilled life and deadening role as mother and wife. Later, while walking by the seashore with the kids, she sees a woman’s naked body washed up on the beach. She tells the kids, 'it’s nothing’ but she must know, we feel, that this corpse represents the victims of the dictatorship who were drugged, dragged into helicopters, and subsequently tossed into the sea below. By the end of the film. Carmen, having been energised and possibly politicised by her encounter with Elías, remains trapped in a marriage that stifles as it shields. She is now a marked woman and seems to have no way out. It is perhaps when we’re cornered that we are most fully alive.

When I sat down with Manuela Martelli, I asked her, with my tongue firmly in my cheek, ‘What happened to Carmen in the end?’ She says that’s for us to say, but my flippant question leads to an interesting discussion of the genesis of the project. Martelli says she’d found Super 8 footage of her maternal grandmother, who she’d never met, while conducting research for the film and almost immediately determined to explore her life during those traumatic times, imaginatively. Her grandmother, she says, dropped out of art school feeling herself to be a failure, had felt deeply unfulfilled, and had herself fallen into a deep depression – in 1976, in the kind of coastal town where the film was shot. Suddenly, all of Martelli’s directorial decisions make perfect sense.

I mention Dominga Sotomayor – who co-produced 1976 with Andrés Wood and whom I’d interviewed 10 years ago when her film Thursday Till Sunday was released. I recall Sotomayor stressing, back then, how hard it was to finance films in Chile, particularly if you happened to be female. It’s a small world, I say, but the world of Chilean cinema is even smaller. That being the case, I ask, did the international reputation of celebrated Chileans such as Patricio Guzman, Pablo Larraín and Andrés Wood weigh heavily on her shoulders, perhaps even make her slightly nervous of ‘covering’ the dictatorship. ‘Not at all’, Martelli says, ‘I’m coming from a woman’s perspective, which is completely different, and this is a very personal film. I made it for all those anonymous women who never appear in history schoolbooks written by men, and for my grandmother who could have done more than she was mandated to do. She had no space.’ I blush as it hits me that 1976 is much more than a thriller and character study, it is also an urgent political film of a different kind to the one I’d expected, a feminist film with a bright, complex woman at its heart and another behind its creation.

Santiago Mitre’s Argentina, 1985 might serve as a perfect companion piece to Pablo Larraín’s No – which presented the cheering tale of the 1988 referendum – during which Chileans voted to pop Pinochet in the dustbin of history. Mitre’s film, like Larraín’s, is an amusing and uplifting crowd-pleaser in which good triumphs over evil, right over might, freedom over tyranny, and hope over fear. It recalls the historic ‘Trial of the Juntas’ – during which Argentina finally faced down the military thugs who, in 1976, toppled the government of Isabel Peron and launched the ‘Dirty War’ against all who stood in their way (including not only the Montoneros and other left-wing Peronists, but also many exiled Chileans who’d fled to Argentina after the Pinochet coup). Chillingly, the junta had declared, ‘The task of disinfection will take us a long time’.

As was the case with Chile’s 1988 referendum, most people believed the despots and tyrants on trial would get off scot-free. Democracy had, after all, only just been restored and remained fragile. Also, there were three former ‘Presidents’ among the nine defendants: Generals Jorge ‘Hitler of the Pampas’ Videla, Roberto Viola, and our old friend Leopoldo Galtieri – who ordered the invasion of the Falkland Islands in 1982, thereby prolonging Thatcher’s term in office and hastening the end of the dictatorship. Galiteri recalls the old Brazilian gag about the snooty Argentinians, ‘Only people this sophisticated could make a mess this big’.

As in Chile in 1988, everyone is pleasantly surprised when the trial goes ahead and justice is done . . . which is not a plot-spoiler, as the outcome of Mitre’s film is never in doubt. In this conventional Hollywoodesque courtroom drama, the fascists are bound to lose and audiences must merely wait patiently for the inevitable happy ending. Argentina and cinema have changed since Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas’s incendiary Argentine tour de force The Hour of the Furnaces. If it feels that Mitre’s film fancies itself for an Oscar and was designed with that in mind, it never loses sight of its political purpose either. In this respect, Argentina, 1985 sits somewhere between worthy antecedents in this careworn genre like Stanley Kramer’s Judgement at Nuremberg or Sidney Lumet’s The Verdict and more muscular recent models like Steve McQueen’s Mangrove and Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Eloísa Díaz’s Repentance, a modern masterpiece of Argentinian Noir, might equally well serve as a companion piece for Argentina, 1985 – even though it’s set in Argentina in 1981. Díaz’s flinty hero is Inspector Joaquín Alzada – an elderly, erudite, slightly curmudgeonly Serpico, if you can imagine such a thing. He is a decent man caught in indecent times who would far prefer the quiet life with his wife to flinching every time the phone rings. Duty, and the dictatorship calls though, so he must plod on. As the novel unfolds, Alzada becomes determined to rescue his revolutionary brother, Jorge, from a military prison. By the time he finally does so, there is little left of Jorge, little that’s recognisably human, and he dies soon after. The parallels between film and book are striking. In Argentina, 1985, Santiago Mitre neither shies from the violence of the state nor allows it to dominate his account of events.

Ricardo Darin plays the Chief Prosecutor, Julio Strassera – an elderly, erudite, slightly curmudgeonly man of integrity whose hard shell protects a vulnerable undercarriage. His soft side surfaces when he’s with his wife Silvia (Alejandra Flechner), his daughter Veronica (Gina Mastronicola), and his son Javier (Santiago Armas Estevarena). Each relationship is given due weight, each is finely draw with an equipoise of elegance and charm. Mitre and co-writer Mario Llinas also leaven the film’s sombre subject matter with rascally humour. And the film is very funny at times, fittingly so given the farcical, almost surreal imbalance of power involved in the legal contest it delineates. Strassera and an associate scratch their heads over who, among the great legal minds of the day, they might realistically approach for assistance in their case against fascism. Their list gradually grows shorter and shorter as they work their way down it: ‘No, fascist . . . dead . . . fascist . . . Super-fascist.’ It feels iffy to be laughing uncontrollably at such gallows humour – hey, fascism is no joke – but the poker-face absurdity of the situation is irresistible and, besides, isn’t humour a defence as well as a weapon, and isn’t it also, as the old saying goes, ‘Thinking in fun while feeling in earnest’.

When Strassera fails to find allies in establishment circles, his idealistic deputy, Luis Moreno-Ocampo (Peter Lanzani), suggests they place their trust in youth. There follows a delicious sequence in which they rally a posse of legal gunslingers, à la The Magnificent Seven, before sending them out on the trail in search of evidence and witnesses. As with each distinct unit of Strassera’s family, these characters arrive on screen fully formed as complex humans, bringing with them bravado, brio and youthful dash. We’re on their side and they, thankfully, are on ours. ‘Strassera’s Kids’ screams one sensationalist headline as media interest begins to grow. And, as the team fan out across Argentina to gather evidence of atrocities, inevitably the death threats increase, and the intimidation intensifies. Moreno-Ocampo’s car explodes before his eyes, but the righteous never falter and the humour never fails.

When an anonymous voice on the phone threatens Strassera that his family will be harmed if he proceeds with the case, his wife responds, ‘Oh, the death threat guy? He’s been calling all afternoon’. In another delightfully mischievous moment, Strassera sits in the courtroom as the complacently smirking generals take their seats, fixes them with his steely gaze, and then makes a crude gesture involving an encircled finger and thumb on one hand, a motion back and forth with the rigid forefinger of the other. The look of horror on Moreno-Ocampo’s face seals the deal.

Such moments of impish humour rightly fall away as the trial enters its critical closing phase. Now Laura Paredes steals the show, delivering the heart-rending testimony of Adriana Calvo de Laborde – who recounts how she was forced to give birth while handcuffed and blindfolded in the back of a police van. As the film rattles toward it’s tear-jerking conclusion, Strassera calmly delivers the hair-raising indictment most Argentinians have been waiting for. ‘Slowly, so that we wouldn’t notice, a machinery of horror unleashed its iniquity over the unaware and the innocent’. His punchline? ‘Never again!’ The trial remains the only case in history in which a democratic government has placed members of a vicious military junta on trial, found them guilty, and placed them behind bars for life. And if that isn’t a happy ending, I’ve never seen one on screen.

We’re duty-bound, Stuart Hall felt, to attend such historic moments of ‘conjuncture’ and assess the economic, political, social and cultural conditions of their emergence. Patricio Guzmán has being doing so, at intervals, all his life. Film theorist Jean Louis Schefer, who died this summer, says, ‘If the cinema is defined by its special power to produce lasting effects of memory, then we must know that through this memory a part of our lives passes into recollections of films’. Along with The Hour of the Furnaces and Chris Marker’s A Grin Without A Cat, Guzmán’s The Battle of Chile can claim to be among the most influential and powerful documentaries of our age, but also one of cinema’s towering mnemonic achievements. There followed his ‘trilogy of memory’ (Chile Obstinate Memory, The Pinochet Case, Salvadore Allende). More recently, we were treated to what we might call his ‘nature trilogy’ (Nostalgia for the Light, The Pearl Button, The Cordillero of Dreams) – his essayistic enquiries into astronomy, demography, ecology, geography, topography and, of course, the importance of political memory. Now in his early 80s, Guzmán returns with My Imaginary Country – still full of vim and vigour, still possessed of a poetic soul and unquenchable political passion – to consider the Social Outbursts (Estallido Social) that swept Chile in 2019 and continue to today.

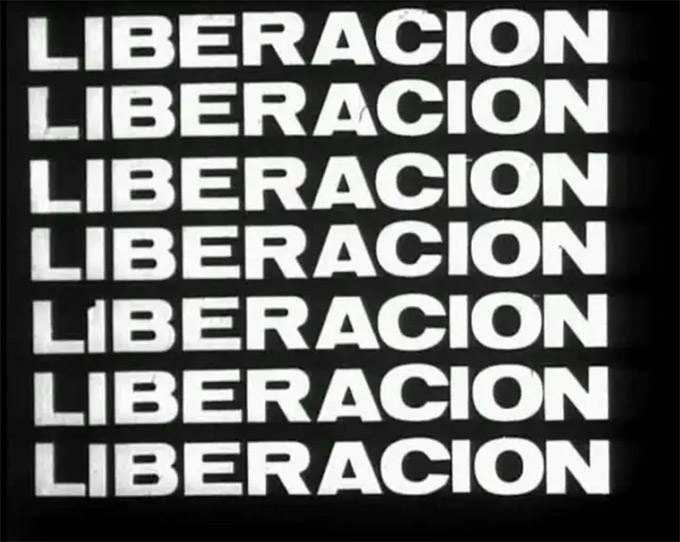

My Imaginary Country, which respectfully references Isabel Allende’s memoir My Invented Country, is both Guzmán’s most personal film to date and, for reasons completely beyond his control, his most deeply melancholic. ‘Memory is our best weapon’, says Valentina Miranda, one of the many young activists, mostly women, who appear in the film. Although Guzmán places this new generation of Chilean radicals centre stage and avoid the spotlight himself, we sense him nodding assent. His latest film begins with acknowledgement of his debt to Chris Marker (without whose assistance The Battle of Chile would never have been completed), and with his own footage of joyful jubilant Allende supporters at the apex of their high hopes for socialism in Chile. My Imaginary Country is infused with Guzmán’s nostalgia for the heady days of his revolutionary youth – when everything seemed possible, optimism seemed like realism, and progressive politics were on the front foot. It is easy to imagine the frisson the veteran director must have felt when the popular fury of young Chileans exploded onto the streets in March 2019 – first to protest price hikes in public transport and, subsequently, in defiance of the economic and political orthodoxies of neoliberalism, against ‘poverty, exploitation, precariousness’.

The rolling protests and massive demonstrations, the optimistic energy and ceaseless invention Guzman charts in My Imaginary Country forced the Chilean Congress to declare a constitutional referendum to consider replacement of the dictatorship’s moribund neoliberal charter. They also underpinned spectacular victories for the left in the constitutional vote in 2020, in the 2021 elections for a Constitutional Convention, and in last November’s general elections – at which Gabriel Boric’s Social Convergence party and the Broad Front coalition defeated the Republican Party and Christian Social Front coalition of far-right candidate José Antonio Kast. Boric won nearly 56 per cent of the vote and became the youngest President, with the largest number of votes, in Chile’s history. With the left in the ascendancy, it must’ve have seemed to Guzman, from his home in France, that history was repeating itself. He recalls Chris Marker’s advice to him: ‘When you want to film a fire, you must be ready at the place where the first flame will appear’. Absent when the revolt burst spontaneously into life in October 2019, he is fully present when he returns to Chile the following year to chart the changes afoot and fathom out what makes a movement wary of leaders and parties tick.

‘This is new’, Guzmán declares, as the women he interviews make explicit the central part guerrilla feminism played, and continues to play in the protest movement. He interviews doctors, students, a journalist, a writer, a chess player, a ‘fellow’ filmmaker, a psychologist – all bar one of them women. He talks to a masked-up mother who worries her daughter may wake up one day an orphan but determines to fight on, for her sake. He talks to a photographer who was partially blinded by the police – one of the movement’s many victims of tear gas, steel batons and rubber bullets. If the cobblestones the rebels respond to police brutality with recall Paris in May 1968 or Tahir Square in January 2011, the act of covering one eye is a freshly-minted symbol of a movement that has already come far and which sees far.

Perhaps most tellingly, Guzmán immortalised by Chris Marker and Joris Ivens in à Valparaiso. They talk about their song ‘Un Violador en Tu Camino/A Rapist in Your Path’ – an anthem of empowerment, resistance and solidarity that went viral and fanned out from Chile to inspire women across the world. In a spectacular keynote scene of breathtaking beauty and potency, we see thousands of women performing a stunning, perfectly choreographed synchronous dance of defiance as they sing: ‘It’s not my fault, not where I was, not my clothes, the rapist is you! It’s the cops, the judges, the State, the President. The oppressive state is a macho rapist’. The message is clear: the emancipation and equality of women is the cornerstone of a new egalitarian politics.

My Imaginary Country recalls the documentary trilogy Tahir 2011: The Good, The Bad and The Politician. When I reviewed that film back then, I wondered if the hope ignited in Cairo could solidify into lasting systemic change. Tragically, it didn’t. The energies unleashed in Chile in 2019, too, have collided with the brick wall of reaction. At the start of the film, Guzmán wonders ‘How is it possible that I am witnessing a second revolution in Chile?’ We are left wondering if he did. One woman says in the film, ‘There are flames that consume and flames that nourish… we’’ll see what happens’. What happened on 4 September, we now know, was a catastrophic defeat for left. 62 per cent of Chileans voted to reject the newly drafted constitution – which enshrined public access to healthcare, free public education, gender equality and rights for indigenous groups. Many on the Chilean left argue that the convention went too far, too fast (where else have I heard that recently?) and that its emphasis on ‘identity politics’ was fatally pressed forward at the expense of class politics.

Yet 79 per cent of Chileans still favour a new constitution, 77 per cent favour gender parity, and 53 per cent support reserved seats in the Constitutional Convention for indigenous groups. If the establishment is closing ranks to deny the demands of the Estallido Social movement, it seems unlikely that the million or so citizens who flooded the streets of Santiago on 25 October 2019 will simply shrug their shoulders and accept a return to business as usual. That rally is one of the stars My Imaginary Country. It was the largest in Chilean history, with numbers present topping even those who attended the closing rally of the No campaign in the 1988 referendum that deposed Pinochet.

Pablo Neruda said, ‘We like to be called the “continent of hope” . . . This hope is like a promise of heaven, and IOU whose payment is always put off’. Now that Bolsonaro, ‘the Trump of the tropics’, has been dispensed with like the Pinochet of Manuela Martelli’s film and the Argentine generals of Santiago Mitre’s film before him, perhaps the activists of Patricio Guzmán’s film will re-engage power with renewed fervour. Perhaps Guzmán will have his work cut out again, soon, to document renewed challenges to the neoliberal, patriarchal status quo and to chart new momentum for change. Chile’s future and Latin America’s, indeed the whole wide world’s future hangs in the balance. It’s now, now or never. |