|

Part 2

And yet the books will be there on the shelves, separate beings

That appeared once, still wet

As shining chestnuts under a tree in autumn

And, touched, coddled, began to live

In spite of fires on the horizon, castles blown up

Tribes on the march, planets in motion

"We are," they said, even as their pages

Were being torn out, or a buzzing flame

Licked away their letters. |

Czeslaw Milosz, And Yet the Books |

A disgraceful example of the insidious relationship between broadsheet reviewers and PR companies serves to set Joe Wright's Anna Karenina in its economic, cultural and ideological context. It's the kind of thing that must have driven Andrew O'Hagan to distraction. On 2nd September, the Sunday before the film's 7th September release date, The Observer published an eight page 'special supplement' dedicated to the film. Its cover is devoted to a lustrous headshot of Keira Knightley, who stars as Tolstoy's doomed heroine, punished for violating the rigid social code to which she is chained and for refusing to relinquish her adulterous affair with Count Vronsky. There she is in all her resplendant glory, her lips slightly parted, the contemporary face of Chanel. Subtle backlighting shines through her spiralling, carefully arranged curls, plays on her bare right shoulder, and highlights the right side of her famously prominent jaw. Light gleams, too, in Knightley's inscrutable, beautiful dark eyes and on the ornately opulent antique necklace displayed above a jaunty hint of lace décolletage. The star-studded full page ad for the film on the rear of supplement and that diamond-studded jewelry, presumably one of the 20 pieces loaned to the film by Chanel, announces what we can expect from the film: a glittering, glitzy, expensive, eye-catching period piece. Tolstoy bequeathed us an epic tragedy. Wright gives us nothing but a pretty farce. A text box note at the bottom of the first page of the supplement warns us not to expect robustly incisive film criticism: "Produced by the Observer to a brief agreed with Univeral Pictures. Funded by Universal Pictures." One wonders what proportion of what kind of marketing budget buys that kind of coverage. One wonders, too, what Guardian stable film critics like Philip French and Peter Bradshaw made of the supplement.

The hard sell begins on the first words of the first article within, as 'Film Critic' Jason Solomons sets the tone for his adulatory piece on the film. He says: "Joe Wright looms out of the shadows of the vast set he's constructed for Anna Karenina. For some reason, as he beams through the darkness, I think of Orson Welles in The Third Man." He closes thus: "The concept is elegant and exciting, a tragedy unfolding almost as a musical, the flow of the images matching the epic sweep of the novel, swapping literary conceits for theatrical ones, yet somehow remaining incredibly cinematic . . . It is a great doorstop of a novel, distilled into a thrilling love story. And Knightley is superb." To the left of the article is Q&A, of sorts, with the actress. Solomons: "You look great in a fur hat." Knightley: "Thanks, I'm a bit of an old pro in a fur hat, having done Dr Zhivago for telly in 2002. But this was different. Anna wore fur and for me it signified that she was suffocating herself in dead skin, trapping herself, making her own cage." Nothing to do with those Russian winters then? Solomons saves his most appalling question till last: "I think you might be busy doing chatshows on the awards circuit for Anna Karenina, you know. Are you comfortable doing that kind of publicity?" Knightly replies with disarming honesty: "I'm not that good at it really. I just try to be as honest as I can without giving too much away. An actress has to preserve a bit of mystery."

Historical costume dramas or 'heritage' films are traditionally associated with cultural conservatism, an ideological tendency that flees troubling contemporary realities by serving up a sanitized, selective version of history that amounts to a systematic distortion of fact, which is to say, a big lie. As Patrick Wright has argued, heritage culture presents the past "purged of political tension" and rendered safe for consumption as visual display through "an obsessive accumulation of comfortably archival detail." You get an awful lot of archival detail and costumery for £31 million, which was the reported budget, give or take a few hundred thousand pounds, Joe Wright had to play with while adapting Tolstoy's tragic morality tale. Two Wrights, here, make a wrong, if one considers what dozens of talented young directors might have done with even a small share of that kind of budget. In cinema, as in society, the case for wealth redistribution seems, to me, as unanswerable as the case that society should face facts rather than bury its head in the sand. Meanwhile, if the question "How many films by Bill Douglas does £31 million buy?" must remain rhetorical, that which asks whether or not we needed another adaptation of Tolstoy's novel answers itself. There have been over a dozen film and TV adaptations of Tolstoy's novel. Not a single decade of the 20th Century passed without another version being added to Vladimir Gardin's version of 1914. This latest addition to the list was an escapist folly, a pointless, if pretty waste of money. The real tragedy of this Anna Karenina is that one senses that Joe Wright – best known for his work with Keira Knightley on adaptations of Pride and Prejudice and Atonement, and commercials for Chanel – sensed this.

In a revealing piece in The Daily Telegraph, Sally Williams "tells the inside story" of the film; or, rather, lets Joe Wright do so. Wright tells Williams about scouting for locations in Moscow and St Petersburg: "You'd be shown around and they'd say, 'Oh yes, we've had seven versions of Anna Karenina shot in this palace before' . . . Then, in England, we were looking around stately homes thinking, 'Well, if we shot it from this angle it could look kind of Russian.' Then someone would say, 'We've had Keira Knightley here five times before.' And it just felt like I was treading the same ground, not only that other people had trod, but also that I'd trod myself." Finding himself trapped in this cinematic groundhog day, and perhaps fearing the law of diminishing box office returns, Wright decided to cut his losses and set the film in a theatre.

He manages the problems theatre has in staging large-scale events by miniaturising them and, in so doing, he miniaturises Tolstoy's novel. He creates a self-referential Gilbert & Sullivan operetta that is pleasing to the eye, expertly executed, generally jolly, but, ultimately, as vain and vaucuous as its titular heroin. From the moment the film opens and a red stage curtain parts, we're trapped in a theatre when we paid to see a film. It might be more accurate to say we're trapped in a parlour guessing game, asking 'Is it a book, a film, a play'? At first we think, er, no, it's none of these. At first we guess it's going to be a musical. The opening sequence, with its brilliantly choreographed clerks dancing elegantly in time, makes us expect an Oklahoma! set in pre-revolutionary Russia. Seamus McGarvey's expert crane shots and zooms, his flashy whip-pan camerawork, reassures us it's a film, but then it begins to look like a self-consciously modern play, with stagehands rushing around hither and thither in full view, and, later, in the obligatory ballroom scenes we're back in a musical. Wright's parents ran the Little Angel Theatre in Islington, perhaps he hatched a plan when young to make a film of a play of a book and set the whole damn thing to music.

When he decided to set the film in a theatre, Wright was, in one sense, one step ahead of himself, as he'd already drafted in playwright Tom Stoppard to write the script. This is not one of his finest moments. If I was blessed with a tenth of Tom Stoppard's talent I'd feel more relaxed about calling the film and his script a failure; if the choreography and costumes, the set pieces and scenery, weren't so impressive I'd feel happier to do so. But, because I prefer film to theatre and believe cinema capable of standing on its own fleet feet, because I admire the architectural grandeur of Tolstoy's novel and believe it smashed here, and because I believe literary characters of depth deserve performances of depth, I'm happy to describe Wright's sumptuous, self-indulgent spectacle as the best piece of theatre, and the worst piece of cinema, I've seen all year. As chatterers say, I don't go the theatre as often as I feel I ought, but, even so, a shudder ran down my spine when I read Wright declare his theatrical confectionary "almost Brechtian" and "audaciously uncommercial." Bertie would turn in his grave, rest his soul. It's not that cinema and theatre can't coexist: Dickie Attenborough's Oh! What a Lovely War, John Cassavetes' Opening Night, Michel Carné's Les Enfants du Paradis, Tim Robbins' Cradle Will Rock, and Tony Richardson's The Entertainer spring immediately to mind as films that show it can. Part of the problem is that, like all heritage films, Wright's Anna Karenina privileges style over substance, and is bedeviled with insubstantial, leaden lead performances.

I looked at how heritage cinema operates in my review of Terence Davies's The Deep Blue Sea here early this year, so, I won't retread old ground (again). I must, however, risk 'bad form' and repeat myself, such is my astonishment that all I said about the performances of Tom Hiddlestone and Rachel Weisz in Davies's film applies, equally and exactly, to those of Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Keira Knightley in Wright's: they "lack either the depth or capacity for abandon necessary to convincingly portray the unhinged passion and incontinent emotion implied" in Tolstoy's novel. Hiddlestone plays Terence Rattigan's Freddie Page as Biggles, Taylor-Johnson plays Tolstoy's Count Vronsky as a little tin soldier with a Biggles moustache and a fresh-from-the-cockpit floppy blonde mop. Rachel Weisz pouts her way demurely through Davies's film as Hester; Keira Knightley pouts her way primly through Wright's as Anna. It came as no surprise to see Knightley fail to convincingly convey the depth of Anna's desire and despair. Hers is as antiseptic an Anna as Vivian Leigh's in the 1948 version. Having seen several versions myself, I'd argue that only Garbo, at her second attempt, in 1935, and Tatiana Samoilova in the 1967 Soviet version, really pull it off. Tolstoy's Anna is more vivacious, voluptuous, tormented and suicidally defiant than Knightley's Anna; his Vronsky is a more complex, cruel, licentious and rough-hewn than Taylor-Johnson's.

The Islington theatre once run by Wright's parents specializes in puppetry; the lead performances in his Anna Karenina are jerky, soulless and wooden. Heritage films often remind me of the old-fashioned 'Major and Miss' illustration which adorned tins of Quality Street until recently. Like that tempting tin of sweeties, they're colourful and contain twist-wrapped dainties. You might indulge yourself once a year, usually at Christmas, but, after the initial sugar rush, you find them so sickly you leave them well alone for a while. Wright's Anna Karenina is like that too, but it reminded me more of those antique revolving clocks with the tinkly chimes, from within which a soldier and a ballerina pop out occasionally, perform a turn right on cue, then disappear. At moments during the film, Taylor-Johnson and Knightley are so bad I wanted them to disappear. Harsh? Well, there's a moment in the film, during a shooting party, when one of the characters rounds on Levin and says, "Did you come here to shoot snipe or criticise'. Myself, I am here to shoot, snipe, and criticise. At another moment in the film Taylor-Johnson's Vronsky says: "You're going to make me look ridiculous." Much as I respect cinema protocol, I was sorely tempted to yell out, with feeling and in the style of Terence Davies: "Imposssible darling, you're already looking ridiculous." Like David Thomson's "absurdly rich young people," Taylor-Johnson and Knightley simply haven't, at present, had the experience of life to play such parts. Even if they had, they wouldn't convince anyway, not because they're too young, but because they're too shallow, and too concerned with "what they have to lose." Of course, actors needn't, maybe shouldn't, exactly replicate the literary characters they play, but being capable of doing so helps them understand their characters and lines at least, while enabling the director to select from a range of emotional and psychological possibilities.

The bachelor Sansón Carrasco speaks for Cervantes when he says to Don Quixote: "There is no book so bad that it does not have something good in it." Godard said something similar about cinema. The hundreds of people who make up the vast cast and crew are to be commended on a thoroughly professional job; the supporting cast but also the teams of carpenters, costume designers, electricians, make-up artists, painters, plasterers, costume designers, and so the list goes on. Just as the leads carry the can while the supporting cast carry the day in Davies's The Deep Blue Sea, so they do in Wright's turkey. Jude Law is convincing as the bloodless, careerist Karenin, Mathew MacFadyen as Oblonsky and David Wilmot as Nikolai Levin are flawless, but it is the carpenters, costumiers, crew and supporting cast who steal the show. One wishes that any one out of Holiday Granger, Shirley Henderson, Emily Watson, Olivia Williams and Ruth Wilson had been offered the role of Anna. They are as superb and superbly cast as Taylor-Johson and Knightley are poor, and poorly cast. Domhnall Gleeson and Alicia Vikander, are equally well-cast and excellent as Levin and Kitty. Sadly, they are only as convincing as they are allowed to be by Wright.

| Mistakes, mistakes, mistakes |

|

Tolstoy was a literary master of mise en scène, a creator of exquisite vignettes, and this might have helped Wright out of the tight theatrical corner he backed himself into, but, no, even with that tendency in Tolstoy to work from, he bungles it. A typical example of Wright's consistent misjudgment is his heavy-handed mishandling of one of the most sensitively crafted love scenes in literature: the dinner party scene at Oblonksy's in which Levin and Kitty are reconciled. Estranged since Kitty's naïve refusal of Levin's marriage proposal, the lovelorn pair initially circle nervously round one another, each uncertain of the other's feelings. Then, after dinner, they peel off from the other guests and tentatively edge their way toward love by discreetly chalking single letters on a card table. The letters stand for words that ever more boldly declare their intentions. The film cleverly replaces chalk with colourful children's alphabet blocks in the film, but, at the delicate moment the couple reach their understanding to seal their match, an old man blows his handkerchief and Wright blows a raspberry at their romantic union. It is a moment so jarring, so unforgivably crass and cynical, and so at odds with Tolstoy's intentions, that we are left clinging to the consoling thought that it was accidental. All the good work Gleeson and Vikander do, indeed all that good work done by all the gifted people involved in the film, is ruined by Wright and Stoppard's decisions not to grant Levin and Kitty the weight Tolstoy apportioned to them and not to take their love seriously. The director and his scriptwriter fatally underestimate both the importance of Levin, who thinks out loud for Tolstoy and acts as a moral commentary on Anna's fate, and that of the Levin/Kitty relationship, which acts as commentary on and counterpoint to the Anna/Vronsky relationship. Such failures simply reiterate an obvious truth, that good books can make bad films and vice versa.

Tolstoy didn't go in for fine aesthetic writing. He didn't mince his words. That wasn't his style. His economical, functional prose focuses the reader's attention on his characters, their ideas, their emotions, their moral positions and social standings. Tolstoy organised what he called, "the endless labyrinth of connections which is the essence of art," so precisely that the novel seems to proceed as plotlessly and naturally as life itself. Nabokov, in his chapter on Tolstoy in his Lectures on Russian Literature, described this kind of work, which generates a sense of witnessing not art but life itself, as 'tiger bright'. Tolstoy's skill enabled him to intertwine several different stories, handle subjects seldom explored in fiction previously (post-puerperal fever and depression), and to deploy – long before Joyce and Woolf – stream of consciousness writing such as that in the magnificent chapter leading up to Anna's suicide. Nothing in the novel is accidental. Nothing is misplaced. Everything is perfectly positioned. Everything is a deliberately designed part of the greater whole. In Joe Wright's version of Anna Karenina, Wright and Stoppard cast aside the details and characters they feel get in the way of a simple love story, consequently the Anna/Vronsky-Levin/Kitty double-plot collapses, and Tolstoy's perfectly constructed architectural edifice comes crashing down.

The detailing of the Zemstvo elections, late-19th Century Russian agricultural policy, pan-Slav nationalism, religious perspectives, and so forth, it is all as essential to Tolstoy's achievement as, say, the details of the whaling industry are to Melville's Moby Dick, of the Austro-Hungarian Empire are to Robert Musil's A Man Without Qualities, or as the Goldstein chapters and Newspeak appendix are to Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Despite being hard up at the time, Orwell refused a request from the US Book-of-the-Month-Club to cut those sections out. Orwell told the BOMC: "A book is built as a balanced structure and one cannot simply remove large chunks here and there unless one is ready to recast the whole thing . . . I cannot allow my book to be mucked about beyond a certain point." It is a shame that Anthony Burgess, whose own dystopian novel A Clockwork Orange owes an enormous debt to Orwell's, didn't emulate Orwell's stand. Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, which Burgess disliked intensely, was based not on Burgess's book, but an already distorted version of it.

Burgess was furious when his US publishers, WW Norton, had insisted that the final chapter of his novel be excised, but he had accepted that as a fait accompli because he needed the royalties. He had written the novel soon after being diagnosed with a brain tumor and given a year to live. Under that death sentence, he wrote at a lick, spurred on by the thought that his royalties would support his then wife, Lynne, after his death. In 1943, she had been attacked and raped during a blackout, while at home and heavily pregnant, by AWOL American GIs. The result was that in that prototerminal year alone he completed six books, including A Clockwork Orange. Burgess's productive dash lends new meaning to the phrase "a labour of love."

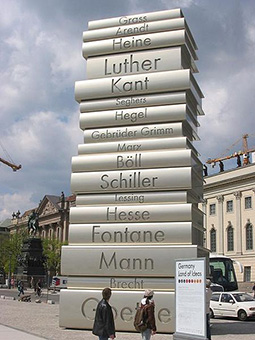

Burgess had plotted the novel so that it contained three sections, each of roughly equal length, each beginning with the same sentence: "What's it going to be then, eh?" More importantly in terms of Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, he had carefully plotted the novel so that it contained 21 Chapters, which equated to our notion of the coming of age. Kubrick, despite having settled in England in 1962, the year of the novel's publication, had only read the bowdlerized US edition given to him by Terry Southern on the set of Dr. Strangelove, so the film was based on that miniaturized version. Wright and Stoppard, similarly, play fast and loose with Tolstoy's novel. That kind of diminishing process tends to happen when great, gargantuan novels are simplified and condensed, but it needn't, as The Tin Drum demonstrates.

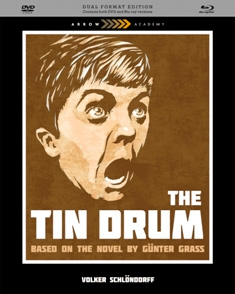

It is hardly surprising, given their content, that controversy greeted the release both of Volker Schlöndorff's 1979 film Die Blechtrommel/The Tin Drum and Günter Grass's seminal 1959 novel of the same name. Both revolve around the otherworldly figure of Oskar Matzereth, the boy who, disgusted by the hypocrisy and mendacity of the adult world, refuses to grow, but who continues to mature, mentally and sexually, within his infant frame. It should be noted that Oskar takes his 'decision' not to grow before the Nazi's seizure of power. Oskar is the product of the ménage à trois involving his Kashubian mother, Agnes Matzerath (Angela Winckler), his "presumptive" German father, Alfred Matzerath (Mario Adorf), and his Polish biological father, Jan Bronski (Daniel Olbrychski). If Oskar is to be believed, and we learn to we take his tall tales with a pinch of salt, he engineers a fall on his third birthday as a cover story for his 'decision' to stop growing, impregnates his German father's teenage mistress, conducts an affair with an Italian circus dwarf while entertaining Nazi troops with his ability to shatter glass with his voice, and 'kills' his mother and his fathers.

The ménage à trois at its heart lead critics to compare The Tin Drum to Truffaut's Jules et Jim, but it might be more productive to compare it with Fassbinder's Effi Briest (1934), Renoir and Chabrol's Madame Bovary (1933 and 1991), and the various versions of Anna Karenina. Effi, Emma, Anna and Agnes all rebel against life with unsatisfying men (Gert von Instetten, Charles Bovary, Alexei Karenin and Hans Mazereth). They each seek romantic and sexual satisfaction elsewhere, disrupt rigorously enforced social codes in so doing, and are punished by suicide (Agnes commits suicide by consuming fish). The similarities are striking; the difference, of course, is that it is Oskar, not his mother, who is at the centre of The Tin Drum. Oskar is the son both of a cuckold and a whore, as the morality of Flaubert, Fontane and Tolstoy's day would have called Agnes. It is made plain in the Director's cut of The Tin Drum that Bronski is the father, when Oskar points at his father's blue eyes and Bronski says to Agnes, "I can't stand him not knowing anymore." It is made plain again when Mazareth says to Agnes, "does it matter who's child it is?" As if Oskar's understandable Oedipal complex and an unsettling plot weren't enough to set the cat among the pigeons, Oskar also beats out the recent histories of Danzig and Nazi Germany on his tin drum.

When Grass's allegorical novel appeared, it was immediately branded blasphemous and obscene, which, by the standards of its day, it was. When Schlöndorff's film version appeared, it was banned in Oklahoma and Ontario as child pornography, which, by any standard of judgment, it is not. The howls of moral outrage that greeted the book in Germany, however, merely masked a deeper dread of discussing the recent past. Grass built on the work of literary predecessors like Heinrich Böll, the exponents of rümmerliteratur (rubble literature) or Kahlschlagliteratur (clear-cutting literature) of the immediate post-war years, to bring Germans face to face with their involvement with the Nazi past as they sought to forget it. Grass shook Germany out of the sleep of dissociative amnesia and pointed an accusatory finger at a people in denial about their collective complicity in the Nazi past, a complicity tellingly delineated in Daniel Goldhagen's Hitler's Willing Executioners. Needless to say, Grass was initially reviled for for his efforts. As he has said: "The publication of my first two novels, The Tin Drum and Dog Years, and the novella I stuck between them, Cat and Mouse, taught me early on, as a relatively young writer, that books can cause offence, stir up fury, even hatred, that what is undertaken out of love for one's country can be taken as soiling one's nest."

The film's reception in North America, meanwhile, revealed a disquieting recrudescence of a censorious sexual politics. The controversy surrounding both book and film did not, however, begin and end with the way each treated Germany's acquiescence and Oskar's sexuality. When Grass was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1999, the Swedish Academy praised his portrayal of "the forgotten face of history." Having established his standing as a respected critic of Germany's treatment of its Nazi past with The Tin Drum, Grass again sent shock waves through German society when, in 2006, he announced that he himself had belonged to the Waffen-SS, albeit as a teenager in the war's closing stages.

This announcement stunned many Germans, not least Volker Schlöndorff, Grass's family, and his biographer, Michael Jürgs. It laid Grass open to charges of staggering moral hypocrisy. He stood revealed as one who had repeatedly exhorted his compatriots to face the past honestly, while failing to do so himself. To many Germans, his reputation for moral integrity was ruined. The ensuing debate took much the same dismal, unenlightening form as the debates around Istvan Szabo's past as a Stasi informant, P.G. Wodehouse's 'Nazi' broadcasts, Umberto Eco's membership of the Young Fascists, and Elia Kazan's capitulation to McCarthyism. Whatever view we take of the matter, it is surely to Grass's credit that he did not freeze, as Sartre did, in nauseated horror in the face of the irrational, on the edge of the abyss. Sadly, we will never know what Jean Améry, Paul Celan and Primo Levi would have made of it all. But, Roman Bucheli wrote in Neue Zürcher Zeitung: "At the end of the 1950s, Grass lived in Paris for four years and was friends with Paul Celan. Of him we learn (from Grass): 'He spent most of his time buried in his work and at the same time trapped in his real as well as excessive fears.' Grass doesn't waste any time considering the possibility that Celan's 'excessive fears' might be founded in the haunting voids of silence to which he is only now conceding . . . Smugly, Grass adds to his memories of Celan: 'When he read his poems aloud, you wanted to light candles'."

The controversy surrounding Grass's wartime behaviour simply stresses how well-placed he was to tackle a nation's guilt, having experienced feelings of guilt himself, not least as a Catholic in the land of Luther. The affair also reveals that he wrote with frenzy partly because he was writing to exorcise the sense of guilt he shared with millions of his compatriots and explains much about Oskar's position: he doesn't directly resist, which is consistent with Grass's habit of berating the fashion to claim resistance credentials, an admirable habit we now view afresh. It also explains much of the darkness of the novel, as does the fact that Grass's mother had been repeatedly raped by Red Army soldiers as they pushed fought through the Vistula on their way to Berlin. My point is that Grass's revelation of his SS past invited a radical re-reading of the novel and therefore Schlöndorff's film, as a 'confession', replete with clues as to the author's own relationship to the Nazi era. It also made the connection between the two unreliable narrators, Oskar Mazareth and Günter Grass, more obvious, and, like the novel itself, the controversy, reminded us of the selective nature of memory while highlighting the dangers of silence, self-deception and the suppression of guilt.

Volker Schlöndorff, too, found himself caught up in controversy only loosely related to the content of his work. When the film was awarded the Palme d'Or at Cannes, the jury's decision was greeted by boos and catcalls. This was not, however, another reactionary manifestation of piety, primness or political amnesia; it was a disgruntled response to festival skullduggery. The Tin Drum was the jury's favoured film but the jurors buckled under pressure from festival organizers to split the prize between Schlöndorff's film and, for the first time in the festival's history, one in production: Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now. Controversial though the jury's decision was, we can now appreciate how startlingly apt it is that these two great anti-war or, in Coppola's preferred phrase, "anti-lie" films were thus conjoined, just as cinema and literature have been. Receiving his Palme d'Or, Coppola grandiosely said of Apocalypse Now: "My film is not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam." Schlöndorff might have granted himself similar poetic license and said of The Tin Drum: "My film is not about the 20th Century. It is the 20th Century." Such myth-making exaggeration wouldn't be in keeping with Schlöndorff's self-effacing style, but his film, like Coppola's, certainly speaks to us from and of the past with a force few other films can match.

Given the significance of Schlöndorff's masterpiece as the turret atop the tower of New German Cinema, and of Grass's magnus opus as the meeting point of European realism and magic realism, it is staggering that we have only recently received them in forms befitting their importance and stature. In 2009, Schlöndorff received a call from Geyer Kopierwerke, the Berlin lab storing the negatives of Die Blechtrommel/The Tin Drum. The lab asked him if he wished to renew his storage license or if they should dispose of the material (60,000 metres of stock in 200 film cans), which included half an hour of footage cut from the film on the insistence of its distributor, United Artists. The original version Schlöndorff showed Grass for approval ran for 165 minutes, but UA required the director to reduce the running time for the theatrical release, to allow for two evening screenings. A year later, and three decades after collecting his Palme d'Or, Schlöndorff returned to Cannes to present his film as he had intended it to be seen, with the deleted footage restored to its rightful place. "This version is not," Schlöndorff says, "a 'director's cut'. It is The Tin Drum – period! We didn't want a different movie; we wanted to produce the real one, the complete one."

Around the same time the extended cut of the film was screening at Cannes, several new translations of Grass's novel, including Breon Mitchell's exemplary English version, were being published to mark the novel's 50th Anniversary. These new translations of the book were prepared with Grass's full co-operation; he even hosted symposiums for translators, leading them on guiding tours of his native city, formerly Danzig, now Gdansk. Borges said: "The taste of the apple is neither in the apple – which cannot taste itself – nor in the mouth of the eater. It requires a contact between the two. The same thing happens to a book . . . the right reader comes along, and the words – or rather the poetry behind the words, for the words themselves are mere symbols – spring to life." Without the right translator, and this applies as much to film 'translation' as to book, 'the right reader' wouldn't taste the tang. Suddenly, one of the most important German novels of the 20th Century and one of the great films of German cinema are available in fully-fleshed versions approved by their creators.

Thanks to Mitchell's translation, and Arrow's Blu-ray release containing the original release and the extended 'director's' cut, we can reappraise both Tin Drums in possession of vital new evidence. Not everybody will be interested in doing so. Several months ago I caught a discussion, on BBC2's The Review Show, of Martin Scorsese's invaluable contribution to film culture, a contribution highlighted by the magnificent restored print of David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia that we were privileged to enjoy last week and which screens in the London Film Festival on 20th October. During the Review Show discussion, panelist Hannah McGill, for whom I have nothing but respect, startled me by saying: "I'm not that drawn to that whole magic of cinema thing, in the same way I'm not drawn to it in The Artist either. I find that nostalgia and sentimentality about the cinema a little bit dubious." I'm not sure what she meant or how she found it 'dubious' as she didn't elaborate. I'm not sure, either, how McGill, who resigned as Artistic director of the Edinburgh International Film Festival in 2010 to become a freelance writer, squares that comment with her role as a regular contributor to Sight & Sound, but the opportunity to see The Tin Drum in a new light highlights an important aspect of how we experience 'that whole magic of cinema thing': the way our reactions to films change with time, in keeping with our changing perceptions of films and the world, and in line with changes in society itself.

Written between 1956 and 1959 when he was resident in Paris, Grass's seminal novel is earthed in the realist tradition but equally indebted to that of European magical realism. Part detailed historic epic, part memoir, part Rabelasian satire, part bildungrsroman, part familienroman, it blends scrupulous detail with deep symbolism and metaphorical insight. When Volker Schlöndorff first read the novel in 1977, he knew immediately that he had to accept the challenge of adapting it – without having the faintest idea how to go about it. The Tin Drum is a novel of such significance, complexity, length and depth that it is easy to see why it was deemed 'unfilmable'. I hope I've suggested ways in which Anna Karenina might be said to be similarly 'unfilmable' above. Written in Paris between 1956 and 1959, the novel is a fusion of fact and fantasy that mixes memoir and myth, satire and slapstick, the real and the surreal in equal measure. From its opening chapter, The Wide Skirt, the book emanates an atmosphere of discomforting strangeness that replicates the disorientating madness of the century it covers. Oskar, suspended between boyhood and manhood, sanity and madness, struggles to make sense of it all. His first words, "Granted: I am an inmate in a mental institution," immediately alert us to his unreliability as a narrator. As I have said, his subsequent lies, omissions and distortions echo those of the German people, and those of Grass himself. Oskar's story begins in 1899, at the moment his mother is, he tells us, conceived beneath his grandmother's skirts in a rain-soaked Kashubian potato field. It ends on Oskar's 30th birthday, in a remapped postwar Europe rebuilding on the ruins of its recent past. In the novel's 560-odd densely packed pages we learn about Oskar's family, his native city, the society spiralling out of control around him, the Second Word War, and its aftermath.

| Schlöndorff's cinematic approach |

|

Much of the novel's power derives from Günter Grass's exuberant linguistic delivery. His bawdy, bawling, sprawling, frenetic, splenetic, enthralling, appalling novel spits words out breathlessly. While many films, like Jean Renoir and Claude Chabrol's adaptations of Madame Bovary, attempt close literal translations of the companion text by reproducing it line by line, this was not an option for Volker Schlöndorff, whom Grass himself described as an "interlocutor." Given the length, content and radical style of Grass's novel, Schlöndorff was forced to be playfully inventive, dipping into a variety of techniques from film history in order to re-present history. Schlöndorff was as well-equipped to do so as anyone. He didn't just learn about his craft while working as Assistant Director on Louis Malle's Zazie dans le metro (1960), Alain Resnais' L'Année dernière à Marienbad (1961), and Jean-Pierre Melville's Léon Morin, Priest (1961), he also learned about film history.

Schlöndorff begins by deploying the techniques of silent cinema. The Tin Drum opens with a scene in which Oskar's Polish grandfather, the nationalist and arsonist Joseph Koljaiczek, hides from police under the skirts of his wife to be and takes full advantage of the situation to consummate their subsequent marriage before the event. This scene was filmed using a 1927 vintage, hand-cranked ASKANIA camera, not only to give a sense of period authenticity, but also to recreate a slapstick mood redolent of the Keystone Kops. Schlöndorff used the ASKANIA again for the wake scene following the suicide of Oskar's mother, in an attempt to recreate the magic of silent cinema and, in particular, by way of homage to Alexander Dovzhenko's 1930 Soviet classic Zemlya/The Earth. The jerky movement of camera and its fixed position grounds the scene in an earlier time. Another scene which reveals Schlöndorff being as playful with cinema as Grass is with literature, is the way he attacks Leni Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will (1935). The 'flame drum' was popular among the Jugenshaft and Hitler Youth but Oskar's flame drum is a subversive tool. Oskar, watching the Nazi rally from beneath the stands, beats out a rhythm on his drum, disrupting the marching songs of the Hitler Youth band and transforming them into a comical waltz in three-four time. Mark Twain, with characteristic wit, said: "A German joke is no laughing matter," but this scene is a comic masterclass. It is also typical of Schlöndorff's use of cinematic codes to subvert the tradition of Nazi propaganda films and debunk fascist culture.

The first casualty of adaptation is, of course, as we have seen with Anna Karenina, is length. There are many examples of films that build on short stories (Frank Perry's The Swimmer, his masterful adaptation of the John Cheever short story, springs immediately to mind), but, generally, adaptation entails a process by which novels are shortened to fit into films. Volker Schlöndorff, of necessity, adapted just the first two of the three books that form Grass's novel. The third book covers Oskar's career as a jazz drummer in Düsseldorf and ends as he prepares to flee his asylum for postwar Paris, while the film ends as the war does, with his family's flight from war-torn Danzig. This foreshortening of the novel may appear to distort the source text, as Joe Wright does Tolstoy's in Anna Karenina, but it actually serves the film well. Reducing the period covered by the novel increased the film's temporal and thematic unity. After cutting the novel's tail off, Schlöndorff was left with the essence of the novel, the rise and fall of the Third Reich, and the history of Günter Grass's native Danzig.

| Danzig and filmed history |

|

As George Lellis and Hans-Bernhard Moeller note in an essay, The Tin Drum in the 21st Century, which appears in the booklet accompanying the Arrow Academy dual format release, "The city of Danzig is central to the whole ethos of The Tin Drum . . . a site of struggle between Nazi Germany's imperialism and Polish resistance." It was where the first shots of the Second World War were fired and, later, it become the site of conflicting political passions again, during the battle between the Solidarity trade union and a repressive state. Located on the border of Germany and Poland, about 230 miles north east of Berlin on the Vistula river, Danzig was, until 1919, the capital of West Prussia. The Free City of Danzig was established as a League of Nations protectorate by the Treaty of Versailles, which also created the 'Danzig Corridor' to allow Poland access to the Baltic Sea. Much of the new city state's administration, notably the Postal Service, was placed in the hands of the Poles, leading to simmering resentment among Germans. The city's multiple identity was further complicated by its position at the heart of Kashubia, a Slavic language region with a centuries-old history. Despite having been persecuted under Bismark's anti-Catholic Kulturkampf, the Kashubs had long lived in harmony with Germans and Poles alike. That commingling of the three peoples is replicated in The Tin Drum, in the love triangle involving the three most important adults in Oskar's life: his mother and two 'fathers'. The arrival of the Nazis put an end to that peaceful coexistence even before the Nazi's assault on Danzig's Polish Post Office, where the first shots of the war were fired and during which Jan Bronski is executed.

In The Tin Drum, Grass wrote from direct experience to document history, in forensic detail. Like Oskar, Grass was born in Danzig to Kashubian-Polish parents who owned a grocer store. Like Oskar does, Grass revolted against Catholicism, fled West after the war, and, fled again, to Paris. Grass painstakingly presents the regional realities of Danzig and Schlöndorff places them on film. Although Godard feels cinema failed in its duty to record the horrors of the holocaust, it has provided a unique, if incomplete record of its century. Talking about his naïve teenage involvement with Nazism, Grass said: "I most likely viewed the Waffen SS as an élite unit . . . I did not find the double rune on the uniform collar repellent . . . Yet for decades I refused to admit to the word, to the double letters." It would come as no surprise if we were to learn that Godard was thinking of Günter Grass when he talks, in Chapter One (a) of L'Histoire(s) du cinéma, of "history(ies) of cinema/news of history/histories des actualités/ histories du cinema/with esses/SSes."

| Oskar, New German Cinema and the Berlin School |

|

Interviewed in 1978, on the set of The Tin Drum, Günter Grass said: "A great deal of Oskar Matzerath is to be found in today's young generation. Many would like to escape the process of becoming an adult and the attendant responsibilities." Oskar speaks to today's generation for the same reason, perhaps even with greater directness due the increased infantalization of culture. He certainly spoke to the post-war generation of Germans, and those who launched Young German Cinema (later to became known as Das neue Kino/the New German Cinema), at the Oberhausen Film Festival in 1962. Volker Schlöndorff was one of the signatories of the Oberhausen Manifesto that declared the old cinema, 'Papa's Cinema', dead and called for a new film language freed from the constraints of commerce. Angered by the amnesia of commercial German cinema in the 50s, the Oberhauseners inaugurated a forensic exploration of the Nazi past and, in so doing, accentuated the generation gap.

Alexander Kluge, one of the most important figures in New German Cinema, highlighted that gap by describing two different kinds of cinema. Kluge says: "At the present time there are enough cultivated entertainment and issue-oriented films, as if cinema were a stroll on walkways in a park . . . One need not duplicate the cultivated. In fact children prefer the bushes: they play in the sand or in scrap heaps." In her article on Kluge in Senses of Cinema, Michelle Langford stresses the importance of the figure of the child to the New German Cinema: "It is the child who, for Kluge and the other 'Young' German filmmakers of the 1960s, represented the hope for cinema, the antidote to the mass-produced products of 'Papa's Kino' . . . it is the child who is least 'cultivated', least affected by the teachings of 'cultured' society. The child is the one who is open to new experiences." She might have added that the child is not only freer, less encultured, the child is also innocent of the crimes of its parents and the past.

It is not difficult to see why Oskar appealed to the generation that grew up in the immediate post-war years. Nor is it difficult to see why he spoke to the generation of German radicals that challenged the state in 1968 and thereafter, for whom Oskar was a kind of refusenik, a liberated dropout. Schlondorff's socialist sympathies lay with the rebels of '68 and that generational response to the Nazi past and the bomb, so he placed even more emphasis on Oskar's rebellious side in the film than Grass did in the in the novel, while, simultaneously, creating an Oskar who reflected the sulky, passive introspection and non-cooperation posture of the defeated left of the 1970s. The complex, hybrid, figure of Oskar speaks still to the loosely linked Berlin School of directors, who look back on the New German Cinema with respect. In 2007, Revolver, the bi-annual house magazine of the Berlin School, gathered together blacklist interviews and published them in an anthology – Kino muss gefährlich sein/Cinema must be dangerous! The anthology features important Berlin School directors such as Dominik Graf, Christoph Hochhäusler, and Christian Petzold – whose collaboration on the Dreileben Trilogy was one of the highlights of last year's London Film Festival and which I reviewed here. It also featured the Berlin School's favourite directors, such as Bruno Dumont, Abas Kiarostami, Peter Kubelka and Jonas Mekas; New German Cinema directors like Werner Herzog, Alexander Kluge and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg; as well as Jean-Claude Carrière, who co-scripted The Tin Drum.

Revolver 26 recently published another anthology, a collection of manifesto statements (available for purchase online in multilingual translation here of which an editorial said: "The outcome is heterogenic, contemporary and gives an impression of a post-post-political generation that does not want to attack Grandpa's or Papa's cinema – but whose fists are clenched nevertheless." It would be surprising if the new generation of German filmmakers are not hostile to Papa's Cinema, because that cinema produced masterpieces such as Berlin Alexanderplatz and The Tin Drum. At any rate, it says much about the provocative power of both Tin Drums that they have challenged successive generations at the level of their deepest phobias. They remain relevant to our moment, addressing the anxieties attendant on the latest crisis in capitalism: racism, xenophobia, religious fanaticism, the power of propaganda and uncritical acceptance of the dominant ideology.

By the time he came to make The Tin Drum Volker Schlöndorff had already amassed considerable experience of adapting the work of others, having adapted Robert Musil, Der junge Törless (1966), Heinrich von Kleist, Michael Kohhaas der Rebell (1969), Bertolt Brecht – Baal (1970), Henry James, Übernachtung in Tirol/Overnight Stay in Tirol (1974), Heinrich Böll, Die veriorene Ehre der Katherina Blum/The Lost Honour of Katherina Blum (1975), and Marguerite Youcenour, Le Coup de grâce (1976). It is surreal but packed with detail, coherent but fragmented and owes as much to Mikail Bulgakov as it does to Alfred Döblin and Thomas Mann. Those respective aspects of, and influences upon Grass's work are reflected in Schlöndorff's film, the influence of which can, in turn, be seen in two subsequent adaptations of equally 'unfilmable' novels: Fassbinder's magnificent adaptation of Doblin's classic Berlin Alexandraplatz (1980), and Vladimir Bortko's reworking of Bulgakov in Sobach'e serdtse/The Heart of a Dog (1988), a masterpiece of late-Soviet cinema. Schlöndorff's make-up artists on The Tin Drum, Rino Carboni and Alfredo Titeri had worked with the likes of Fellini and Visconti, and the influence of Fellini is clear in the film, particularly the Fellini of Amarcord. In his journal on the making of the film, Schlöndorff compliments Fellini on the way he treats political infantalism, noting "the way in which the adolescent dependencies of Italian men provided fuel for the growth of fascism."

Schlöndorff's work, and The Tin Drum in particular, is part of that ongoing conversation, interplay and exchange between books and films. The connections between seemingly unrelated films – as I hope my glance at The Artist, Apocalypse Now, Hugo, The Tin Drum has shown – are typical of that layering of texts referred to by Christine Geraghty in her work on intertextuality: that steady "accretion of deposits," that "shadowing or doubling of what is on the surface by what is glimpsed behind." Typical, too, of Thomas Leitch's vision of texts, "afloat upon a sea of countless earlier texts from which it could not help borrowing."

< Part 1

|