|

Over the last couple of decades, the BFI London Film Festival has firmly established itself as an essential event on the international festival calendar – for distributors, filmmakers, actors and audiences alike. Under the artistic direction of Adrian Wootton and Sandra Hebron, the Festival earned its reputation as the 'festival of festivals' in more ways than one. Not only did it continue to harvest the finest films from other festivals in order to showcase the best in world cinema, it has also consolidated its identity as a true People's Festival – with audience figures up to an impressive, record-breaking 132,000 last year. For two autumnal weeks, London is at the centre of the cinematic world and audiences revel in the moment.

When I interviewed Adrian Wootton shortly after he resigned as Director of the London Film Festival to take up his new position as CEO of Film London, he spoke of the LFF with evident pride and of his time with the BFI with the trace of a tear in his eye. A cloud passed over the normally ebullient Wooton's face as he confessed that he'd miss his leading role in the Festival. The sense of sadness that swept his features only passed when he chuckled at them memory of being whipped around the stage of NFT1 by a mock-angry, belt-wielding Nani Moretti. As Sandra Hebron, in her turn, steps aside as Festival Director, it is a safe bet that she will hand over to her successor Clare Stewart with similarly mixed emotions of wistful affection and pride in a job well done. We look forward to hearing her memories of Festivals past and will report our findings here.

In her final introductory notes to the Festival catalogue, Hebron quotes Alexsandr Sokurov, whose career to date will be celebrated by a two-part BFI retrospective beginning, as the 55th London Film Festival ends and delegates return to their native lands, with a personal appearance in NFT1 on 29 October. Speaking in Venice as he collected a Golden Lion award for his latest film, Faust (one of the hot tickets of this year's LFF), the Russian maestro said: "Culture is not a luxury; it is the basis for the development of society." Sandra Hebron also cites critic Thomas Elsaesser's dictum that film festivals are an opportunity for "reflection and renewal."

Those comments sprang to mind as I watched Alberto Morais' second feature, Las Olas/The Waves, on the Festival's first day proper. The film, which picked up the top prize at the 33rd Moscow Film Festival earlier this year, is the latest to attempt a breach of Spain's collective amnesia about its Civil War and generate reflection on that cataclysmic, century-defining clash of ideologies. When I interviewed Morais, he spoke of the damage done to Spain's development, not only by the defeat of democracy in the Civil War, but also by Franco's subsequent suppression of cultural life. He suggested that the scars left by the Civil War on the Spanish national psyche would not heal without open discussion of it and that, in the absence of meaningful public conversation, the wounds of that time had grown gangrenous and festered during 'the Transition'. There can have been no better film than The Waves with which to begin the Festival, for, flawed though it is, it is a powerful reminder of why cinema, the art of form of the 20th Century, continues to matter in the 21st Century.

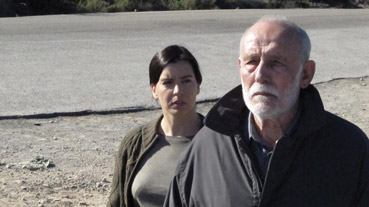

The idea for The Waves formed in Morais' mind after a conversation he had with Theo Angelopoulus while shooting his debut feature, Un lugar en el cine/A Place in the Cinema (2007), a documentary on neo-realism built around interviews with Angelopoulus, Victor Erice and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Angelopoulus told Morais that, "Conversing with History is conversing with oneself." The Waves feels, for good and ill, like a conversation between Morais and himself. A beautifully paced road movie like no other, it approaches the Civil War obliquely, through the eyes of Miguel (Carlos Alvárez-Nóvoa), a recently widowed 80-year-old belatedly coming to terms with his past. He travels from his home in Valencia to Argelès-sur-Mer in Southern France, where many tens of thousands of captured Republicans had been held in concentration camps by the French government after the collapse of the Republic. Those men and women had been fortunate to survive the barbaric slaughter perpetrated by Franco's troops as they swept through the last die-hard pockets of Republican resistance on the Mediterranean seaboard and in Catalonia, but few were fortunate to survive the camps. This was what the Russian poet Ilya Ehrenburg called, "The tomb not only of the Spanish Republic, but also of European democracy."

Miguel, the embodiment of Spain's pained struggle to remember, is beset by physical ailments, perhaps aware that he is dying. His car breaks down halfway through his journey and we watch the film tense from the start with a sense that he might break down too. Although the film opens with a quote from legendary photographer Robert Capa – who was appalled by what he saw in Argelès – a creased photograph of Miguel behind the barbed wire is as a close as we come to the experience that scarred Miguel for life. There are occasional, unsettling glimpses of the Civil War as Miguel's memories explode onto the screen, but the film steers away from direct confrontation with the past while allowing it to seep into every frame. Morais allows the film to unfold of its own accord and at its natural pace, insists that less is more, and displays a disciplined restraint and elegant economy of style that would be the envy of many far more experienced directors. He invites us to join Miguel on his journey to the past and forces us to think about it as we watch Miguel think about it.

Given that Morais regards Ken Loach's Land and Freedom (1995) as the most successful cinematic treatment of the Civil War, his choice of such an elliptical, meditative form is puzzling. When I asked him why he hadn't made a film closer in style to Loach's, he laughed, hunched his shoulders, raised his palms upwards, and said: "I don't think I could have. It would be very difficult. That is a great, great film." Becoming serious, he continued, "I am very close to Loach politically but I come from a different generation. We can talk about history differently, with an approach to it more rooted in cinematic modernity. We cannot make films with our fists in the air." When we discussed his spared down style, Morais explained that in directing Carlos Alvárez-Nóvoa, who is renowned in Spain primarily for his great work in the theatre, he had to ask the veteran actor to shed his thespian skin and unlearn his skills. In successfully persuading Alvárez-Nóvoa to do so, Morais coaxed out of him a majestic performance of intense gravity and quiet force. Morais, who was born in Valladolid in 1976, a year after Franco's death, may not bristle with the kind of combative energy Ken Loach brings to his films but his intelligent, skillfully executed, gently moving film makes a significant contribution to Spain's attempts to untie the knots of its history. I will, as it were, return to Spain later in the festival, when I consider Benito Zambrano's The Sleeping Voice, a film which, Maria Delgado informs me, adopts a different, more conventional approach to Spanish history, one closer to Loach's than Morais'.

|

|

|